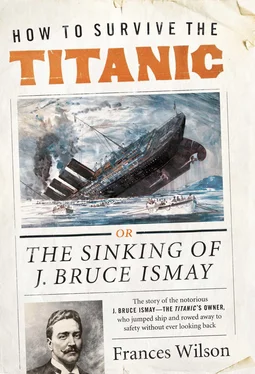

On 25 April, Ismay replied, in pencil, to a letter he had received from the brother of the artist, Francis Millet, who had gone down with the ship. ‘I regret extremely’, he said, that ‘I had not the pleasure of meeting your brother and am therefore unable to give you any information in regard to him.’ Ismay expressed his condolences, adding that ‘I would also like to say that I am not in any way responsible for the truly dreadful disaster which God knows, if it had been possible, I would have done anything in the world to avert. We had the finest ship in the world, and appointed as her commander a man in whom we had absolute confidence. Why people try to make me responsible for the horrible disaster I cannot imagine. The last week has been a horrible nightmare to me, and I cannot yet realise the Titanic has gone. I can only hope God will give me strength to see the matter out to the end. I am having a truly awful time.’ 23

Later that day Ismay wrote to Senator Smith reminding him that ‘though under severe mental and physical strain’ he had ‘welcomed this inquiry’ and placed himself at the disposal of the committee. ‘Though not in the best of condition to give evidence’, he had ‘testified at length’ the previous Friday. Since then he had attended every hearing and held himself in readiness to answer all the committee’s needs, ‘though personally I do not see that I can be of any further assistance’. Might it be possible, he implored, ‘if the committee wishes to examine me further’, for it to do so ‘promptly in order that I may go home to my family’, especially now that the British government had begun its own inquiries ‘which urgently require my personal attention in England’?

Smith responded immediately. ‘I can see that your absence from England at a time so momentous in the affairs of your company would be most embarrassing, but the horror of the Titanic catastrophe and its importance to the people of the world call for scrupulous investigation into the causes leading up to the disaster… I am working night and day to achieve this result, and you should continue to help me instead of annoying me and delaying my work by your personal importunities.’ In London, an editorial in the Saturday Review asked: ‘Why should British subjects be detained against their will… in order that a blustering ignoramus may tease them with questions about the difference between the “bow” and the “head” of a ship, the origin of icebergs and the use of watertight compartments?’ Senator Smith afterwards declared that ‘energy was more desirable than learning’, and ‘If I asked questions that seemed absurd to sailors, it did no harm. Everybody isn’t a sailor, and lots of people who have never been to sea want to know all about the loss of the Titanic, even down to the inconsequential details that the marine experts scoff at. And I know we got the truth.’

During the week, Ismay had listened as the inquiry span itself away. He seemed like a spider trapped in an enormous web; his simple story now had sidetracks which led nowhere, cross tracks which started back and began anew. He was entangled, but he could also see more clearly. He gained a fuller sense than ever before of the world inside his ships; he got to know his employees, his passengers and the names of the crew who had died; he heard how the firemen, engineers and Marconi operators had never left their posts; he learned how wireless worked, how on the port side Lightoller was operating a ‘women and children only’ policy while on starboard they were loading women and children first, and he was forced to imagine what the ship had looked like when she went down. He heard that the Californian, a fellow ship in the IMM combine, had been eight miles away all night with her wireless turned off. He heard accounts of miraculous survivals, and he re-imagined his own death again and again. Did the hundreds who died see, as drowning figures are meant to do, their lives pass before them? Would that not have been a better fate than a survival with no future? Had he gone down with the ship, what would the papers be saying about him now? Who then would be their scapegoat? Ismay understood that every person saved was seen to be taking the place of someone else who had more right to a life. He learned that no one, not even women and children, was allowed to survive the Titanic.

What constituted a child anyway? Lightoller had ordered Emily Ryerson’s son, a boy of thirteen, to stay on board with the men; the child only joined his mother in the lifeboat when his father, a powerful steel magnate, intervened. ‘No more boys’, a frustrated Lightoller was heard to mutter. Some men felt that the women who owed their lives to male gallantry were hypocrites, and witness after witness described how wives and mothers in the lifeboats had refused to return to their dying husbands and sons. Real wives were those like Ida Straus, who remained on board with her husband of fifty years, the owner of Macy’s department store. ‘Where you go, I go,’ Mrs Straus reportedly said. But Mrs Stuart White, a first-class passenger who lived at the Waldorf-Astoria, believed the women in the lifeboats had been braver than the ‘heroes’ who only stayed on the ship because they thought it was the safer option. ‘I do not think that there was any particular bravery,’ Mrs White told the inquiry, ‘because none of the men thought it was going down.’

By the end of the inquiry, Ismay knew more about those final hours than anyone else who had been unlucky enough to survive the Titanic.

The crewmen were finally released on 29 April, but Ismay was not. The next day the Mackay Bennett, contracted by the White Star Line to search for bodies, returned to Halifax. They had found 306 of the 1,500 dead. In the opinion of the surgeon who accompanied the ‘funeral ship’, most had lived for four hours in the water before freezing to death. Those who could not be identified were buried at sea, and 190 others, including the body of John Jacob Astor, were brought home.

When Ismay was finally called to the stand for the second time on 30 April, Senator Smith found himself addressing an apparently contrite and more responsive man. Perhaps Ismay was relieved: no one else from Collapsible C had been cross-examined, not even William Carter, who had left the ship with him, or Quartermaster Rowe, who had taken charge of the boat and knew whether or not Ismay had been rowing; nor had Dr McGhee been called to answer questions about Ismay’s state of mind while on the Carpathia. The inquiry was drawing to a close and apart from the claims that Emily Ryerson had made in the press, which she was due to swear in an affidavit the following day, Senator Smith had not been able to pin a thing on Ismay. He understood that speed was of less importance to the White Star Line than luxury, that Ismay did what he could to lower and load the boats on the starboard side, and that whether he jumped into Collapsible C or was pushed, he was in one of the last boats to leave. It was tacitly agreed by the Senate Committee that Ismay had done his duty, without anyone’s knowing quite what that duty was.

Most of what Smith now asked him mirrored what he had asked before. Having questioned Ismay about the structure of the IMM, the relationship of the White Star Line with the Morgan combine and Harland & Wolff, and their arrangement with the British government to deliver the mail, Smith asked Ismay to explain once again his role on the Titanic. Was he there officially for the purpose of inspecting? Ismay replied that he had not yet made any inspection of the ship at all, that during the voyage, he was never outside the first-class passenger accommodation on the ship. Ismay repeated that he had not dined with the Captain on Sunday night, that the Captain had been at a dinner for the ship’s most prominent figures organised by the Wideners (to which Ismay, despite knowing George Widener, was not invited). He explained that the ship was insured for $5 million and expressed horror at the suggestion that an attempt might have been made by him to reinsure the vessel on Monday 15 April. It was a horrible accusation and Ismay would have considered any such action entirely dishonourable. He was asked to read aloud the same Yamsi messages read by Franklin the week before, and to give the time and context of each. He was asked to confirm the speed of the ship, and to say whether ‘anyone had urged the Captain to greater speed’ than seventy revolutions. It is really impossible, said Ismay with disgust, to imagine such a thing on board ship. He replied, when asked if he did not ‘regard it as an exercise of proper precaution and care to lessen the speed of a ship crossing the Atlantic when she had been warned of the presence of ice ahead’ that it was a question I cannot give any opinion on. We employ the very best men we possibly can to take command of these ships, and it is a matter entirely in their discretion.

Читать дальше