In The Ismay Line, Wilton Oldham recounts how on Bruce’s first day at work he left his hat and coat on his father’s stand, as he had done throughout his childhood. ‘Please inform the new office boy’, Ismay Senior asked one of his clerks, ‘that he is not to leave his hat and coat lying about in my office.’ By means such as this, Oldham suggests, Thomas ‘implanted’ in Bruce ‘the sense of inferiority’ he then carried all his life. But what is striking about the tale — apart from the fact that Ismay Junior could not distinguish between the etiquette of work and that of home — is that he was so wounded by his father’s insistence that he use the same cloakroom as his new colleagues that, in the words of Oldham, ‘he rarely wore a coat again’.

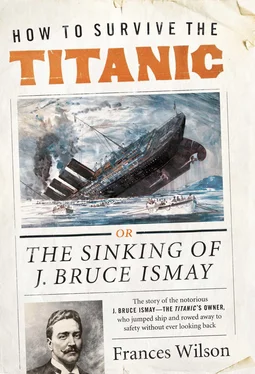

At around the same time, he returned home from work early one evening and, without asking permission, took his father’s favourite horse for a gallop along Crosby Sands. When the animal broke his leg and had to be shot, Thomas’s rage was such that Bruce ‘never rode again’. This pattern was to be repeated throughout his life: when his own eldest son died as a baby, Ismay found contact with his next three children difficult; when his second son, Tom, caught polio, he further distanced himself — ‘Bruce possessed that curious trait which some people have,’ wrote Oldham, ‘in that he shrank from anyone who was not physically perfect and after this his attitude to Tom was tinged with this involuntary repugnance.’ When the Titanic was sinking, Ismay could not watch, and he then never went to New York again.

Oldham, who is an apologist for Bruce Ismay — ‘I have always felt that he was the most misunderstood and misjudged character of the early part of the century’ — edges around the tricky relationship between father and son. 17Bruce, he writes, ‘was devoted to both his parents and his mother loved him too; but his father found him difficult’. If Bruce was ‘brusque and arrogant’, filled with ‘destructive criticism’ and a ‘biting sarcasm’, it was because he had been broken by his father’s ‘constant humiliations’. There was, Oldham says, ‘a feeling of constraint between them owing to Thomas Ismay’s unconscious jealousy of [Bruce]’. The ‘friction’ between them was such that they could not occupy the same house or be in the office at the same time as one another. Oldham’s comments are the result of conversations with Ismay’s widow, Florence, then in her nineties; the specific reasons why Thomas might have found Bruce difficult are not discussed, and nor does Oldham offer reasons for the mutual ‘friction’ or the ‘unconscious jealousy’. What is clear is that Thomas Ismay, who generally found people easy to deal with because they did what he told them to do, was irritated by Bruce, who did not. Yet Bruce was the only one of the three sons, including Thomas Ismay’s favourite, James, to share his father’s love of ships and shipping, and the only one prepared to devote himself to the White Star Line. Ismay Senior was a tycoon who dreamed of heading a dynasty, and Bruce was the means by which he could achieve his ambition. James, who had no interest in ships, proved himself an excellent landlord and farmer, while Bower — Ismay’s favourite brother — grew into an Edwardian dandy who squandered his father’s money on racehorses. The only explanation Oldham gives of the loathing between Thomas and Bruce is that Bruce ‘was quick to learn and when asked his opinion would state it clearly and forthrightly; Thomas Ismay liked to consider a problem from all angles before reaching a decision, and so resented his quick-thinking son’. Bruce was, according to those who worked for him, dogmatic and dictatorial; he would brook no argument and his insistence on punctuality verged on the fanatical. The problem for Thomas was that Bruce was the same as him and different, and he feared both aspects of his character. He wanted his eldest son to be his mirror image but not to occupy the same space. Thomas provided him with palatial homes, fleets of servants and an upper-class education, but then resented him for having it easy. Bruce grew up knowing that he was not himself but a failed version of someone else; he was never to forget that he was an inferior model, an imperfect copy. 18

In 1877, when Bruce was away at school, Thomas Ismay bought a house surrounded by 390 acres of melancholy, dank land in Thurstaston on the western Wirral, overlooking the sandbanks of the River Dee and twelve miles by ferry from Liverpool. The Ismays’ former home of Beech Lawn was in a suburb inhabited by sea captains and ship’s officers. Captain E. J. Smith had at one time lived around the corner and Joseph Bell, the Titanic ’s Chief Engineer, lived down the road, as would, at various points, Captain Rostron of the Carpathia and Second Officer Charles Lightoller. Now that Thomas Ismay had become rich, he needed to set himself apart from his employees. He needed his own Xanadu.

Throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, the Liverpool suburbs were filling up with merchant palaces. ‘Crowds of comfortable and luxurious villas’, wrote a journalist in 1873, ‘besprinkle the country for miles round Liverpool, inhabited by shipowners, ship-insurers, corn merchants, cotton brokers, emigrant agents, &tc, &tc, men with “one foot on sea, and one on shore”’. One such villa was Broughton Hall, the home of Gustavus Schwabe. A Gothic Revival mansion (today a convent), Broughton was built for Schwabe in 1859 and it was here in 1869 that the agreement had been made between Thomas Ismay and William Imrie to resurrect the White Star Line. Thomas Ismay’s purchase of the land at Thurstaston was a demonstration of how successful the previous seven years had been. Imrie, meanwhile, had moved into a grand pile called Holmstead on the North Mossley Hill Road. A patron of the arts, Imrie filled his house (now also a convent) with Pre-Raphaelite paintings, including his collection of works by Evelyn De Morgan. Holmstead was the epitome of modernity and discernment: Rossetti’s Dante’s Dream could be found above the fire in the library next to a stained-glass window by Morris and Co., and Edward Burne-Jones’s The Tree of Forgiveness was displayed upon William Morris wallpaper in the music room where Imrie and his wife would host singing evenings. Frederick Leyland, another self-made Liverpool shipowner who patronised contemporary artists, entertained Whistler in his own new manor house, Speke Hall, eight miles out of Liverpool. Thomas Ismay’s house would prove him likewise to be a man of taste: his home would be the perfect marriage of money and art. He would appear to all the world the image of fulfilment.

Ismay Senior liked making things — in the garden of Beech Lawn he had built a grotto consisting of large rocks faced with mirrors which surrounded a sunken well and iron spiral staircase — and he now decided to demolish the existing house in Thurstaston, built only twelve years earlier, and start again. He would ask the most fashionable architect of the day to design him a mansion that would overshadow all other mansions. Not one nail would go into its construction: Thomas wanted the building held together by brass screws alone. No reason is recorded for this particular eccentricity but it is possibly because the house would then resemble a ship, where steel plates are bolted together by rivets. To gather ideas for his new project, he and Margaret began a tour of English manors and in January 1882 they visited Adcote in Shrewsbury, designed by Richard Norman Shaw for the Darby family, the industrialists who built Ironbridge. Shaw’s style was a combination of ‘merrie Englande’ and Gothic Revival; an admirer of Pugin, Shaw designed vernacular buildings typified by severe outlooks and soaring, twisted chimneys; other signature touches were half-timbered bay windows, inglenooks, stained glass and high ceilings. Thomas Ismay liked his style and asked Shaw to give him something akin to Adcote, only bigger and better. He wanted a modern house which impersonated an ancient house, something which, as Charles Ryder would describe Brideshead, looked as though it had grown silently with the centuries, catching and keeping the best of each generation.

Читать дальше