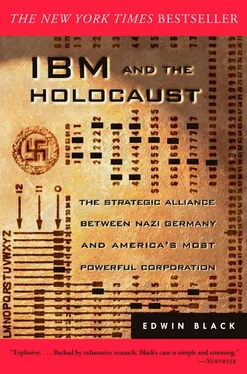

The stakes must have been high for Watson to disregard the gargantuan protest of a nation, and the world’s battle cry to isolate Germany commercially. But IBM maintained its steadfast commitment to an alliance with Nazi Germany. It was just days later that Watson launched the effort to garner the Prussian census contract.

Germans understood Watson to be a friend of the Reich. Just after the Madison Square Garden event, senior management at Dehomag sent their company Leader a jointly signed appeal on firm letterhead. German managers implored Watson to help suppress the “cruelty stories depicting pretended abominable crimes against German jews… [which] are untrue.” The word “Jews” was not capitalized. Heidinger could not bring himself to capitalize the letter “J” when typing the word “German” next to the word Jew. “We are applying to our esteemed foreign personal and business friends,” Dehomag wrote, “with the most urgent request, not only to reciprocate our cooperation but—as champions of truth—not only not to believe similar unfounded rumors, but to set yourselves against them.” 57

Watson did not disappoint his colleagues in Berlin. Just after the worldwide rallies in late March, Dehomag board meetings in Berlin confirmed, “President Watson and vice president Braitmayer were fully agreed that we should manufacture all suitable items in Germany according to our best lights and by our own decision.” Hence, plans to establish a factory were to proceed, even though certain highly technical parts would still be imported from the United States. Watson’s office routinely received translated copies of the meeting minutes a few days later. 58

Watson’s commitment to growing German operations seemed indefatigable. He ignored the tide of America’s anti-Nazi movement and the risk of being discovered as a commercial associate of the Third Reich. But doing so meant ignoring the inescapable financial risk any businessman could see in Nazi Germany. Simply put, doing business in Germany was dangerous.

Foreign business was fundamentally considered an enemy of the German State. Incomes earned by foreign corporations could not be transferred overseas. They were sequestered in blocked German bank accounts. The money was usable, but only in Germany. Hence, a dollar of profit made by Dehomag could only be spent in Germany, binding any foreign enterprise to continued economic development within Germany. Companies were frequently required to invest their profits in Reich bonds. Many considered this monetary move little more than Hitler’s effort to take American business hostage. Others understood that as corporations fled Germany, the Reich was forced to decree that their money would have to remain behind.

IBM’s Paris office began regularly receiving statements from the Deutsche Bank und Disconto-Gesellschaft, listing Dehomag’s distributions as blocked funds in the name of International Business Machines Corporation. For example, one account balance of RM 188,896 was suddenly boosted by RM 90,000—almost none of which could be sent back to America. 59

Rapid-fire regulations designed to subdue the independence of foreign business were being promulgated almost daily. Often regional rules were simply decreed by a local party potentate. Companies were obligated to fire Jews, hire from the ranks of the NSDAP—the Nazi Party—pay special contributions, and sometimes even defer plans for mechanization on the theory that certain types of machinery displaced jobs. Conflicting rules from conflicting authorities were commonplace.

Most of all, Germany loudly warned all foreign business that they were subject to a concept known as Gleichschaltung, loosely translated as “total coordination” with the State. Within days of Hitler’s rise to power, the process of Gleichschaltung began as every political, organizational, and social structure within German society was integrated into the Nazi movement and therefore made subordinate to NSDAP goals and instructions. Gleichschaltung applied to business as well. Foreign business quickly realized it. And they were reminded often. 60

April 7, 1933, New York Times : A page one article bannered “Nazis Seize Power to Rule Business; Our Firms Alarmed,” led with the assertion, “Adolf Hitler, having made himself political dictator of Germany, today became dictator of German big business as well.” The New York Times explained that, “every phase of German business had already been thoroughly organized. By taking control of the business organizations, the Nazis have obtained control of the interests they represent.” 61

April 28, 1933, New York Times : In an article headlined “Germany Cautions Foreign Business,” the newspaper prominently reported a promulgation by Reich Economics Undersecretary Paul Bang, “The German government… must demand that foreign business establishments unreservedly participate in the realization of Germany’s economic program.” 62

To complete the circle of apprehension, everywhere the talk was of renewed war. Any economic transfusion to the Hitler regime was seen by many as a mere prelude to another horrific military conflict. Officials in Washington, diplomats in London and Paris, and business leaders throughout the world feared that the advent of Hitler would throw humanity back into a global war. Signs of German rearmament were reported continuously. Open declarations by Germany that it would reoccupy tracts of land seized by the victorious Allies were blared throughout the media. A key source of alarm was Hitler’s so-called employment program.

Germany was disarmed as part of the Versailles Treaty. Now labor forces were becoming facades for military recruitment. Organized “labor units” were subject to conscription, wore uniforms, and underwent paramilitary training. Typical was a New York Times report on May 21 headlined “Reich Issues Orders for New Labor Units.” The subhead read, “Military Tone Is Evident in the Conscription Regulations—Storm Troops Favored.” 63

Why would one of America’s leading businessmen and his premier corporation risk all by participating in a Nazi economy sworn to destroy Jewry, subjugate Europe, and dominate all enterprises within its midst? For one, IBM’s economic entanglements with Nazi Germany remained beneath public perception. Few understood the far-reaching ramifications of punch card technology and even fewer had a foreground understanding that the company Dehomag was in fact essentially a wholly-owned subsidiary of International Business Machines.

Boycott and protest movements were ardently trying to crush Hitlerism by stopping Germany’s exports. Although a network of Jewish and non-sectarian anti-Nazi leagues and bodies struggled to organize comprehensive lists of companies doing business with Germany, from importers of German toys and shoes to sellers of German porcelain and pharmaceuticals, yet IBM and Watson were not identified. Neither the company nor its president even appeared in any of thousands of hectic phone book entries or hand written index card files of the leading national and regional boycott bodies. Anti-Nazi agitators just didn’t understand the dynamics of corporate multinationalism. 64

Moreover, IBM was not importing German merchandise, it was exporting machinery. In fact, even exports dwindled as soon as the new plant in Berlin was erected, leaving less of a paper trail. So a measure of invisibility was assured in 1933.

But to a certain extent all the worries about granting Hitler the technologic tools he needed were all subordinated to one irrepressible, ideological imperative. Hitler’s plans for a new Fascist order with a “Greater Germany” dominating all Europe were not unacceptable to Watson. In fact, Watson admired the whole concept of Fascism. He hoped he could participate as the American capitalistic counterpart of the great Fascist wave sweeping the Continent. Most of all, Fascism was good for business.

Читать дальше