The readers of popular magazines at the beginning of the twentieth century were enthralled by scientific stories such as ‘Röntgen’s Curse’. This appetite for scientific romances was encouraged first by the immensely popular adventures of Jules Verne and then by Wells’s short stories and novels, fictions which broadened the childhood horizons of Edward Teller, Leo Szilard and many others. In the pages of these journals, fact and fiction rubbed shoulders. Stories by Wells about fictional scientists might be printed in the same issue as a factual article about the miracle of X-ray photography or the next great scientific wonder. A public which had little scientific education was thrilled by tales of Promethean struggles in the laboratory, whether they were imagined or true. Science was hot news, and Röntgen and other scientists were heroes, modern-day wizards who held their audiences spellbound with the wonders of nature and who promised to conjure them a brave new technological future. Science was going to change the world.

The All-Master sealed a symbol of His might

Within a stone, and to a woman’s eye

Revealed the wonder. Lo, infinity

Wrapped in an atom – molecules of light

Outshining centuries! No mortal sight

May fathom in this grain the galaxy

Of suns, moons, planets, hurled unceasingly

Out of their glowing system into the night.

John Hall Ingham, ‘Radium’ (1904)

As the new century dawned, forecasters confidently predicted that an age of ‘universal progress’ was about to begin, with science and technology in the vanguard. 1The illustrated monthly magazines, which had revolutionized the reading habits of millions of ordinary people in Britain and America, were the heralds of this new age. The nineteenth century had been, to quote the populist Strand Magazine , ‘the century of Science writ largest’. Science had fathered inventions which had utterly transformed society: ‘railways and steamships, telegraphs and telephones, electric lighting and traction, the phonograph and the motor-car, Röntgen’s rays and Marconi’s messages’. No one could doubt that the twentieth century would more than match this ‘record of the marvellous’. 2

Of course, not everyone was happy with this brave new world. In 1907 one American commentator complained bitterly that ‘the scientific spirit seems now to dominate everything. The world in future is to be governed from the laboratory.’ 3But this was a minority view. W. J. Wintle, writing in the Harmsworth Magazine , asked: ‘Will the world be better and happier in the new century?’ His answer was ‘unquestionably in the affirmative’ because ‘[s]cientific progress tends to moral advancement’. 4The mechanized slaughter of World War I would show just how little progress had been made in the field of morality. But thirteen years before this war to end wars broke out, the Harmsworth could still beguile its readers with the technological wonders of tomorrow’s world.

Mr Wintle thought that by ‘the end of the twentieth century the man in the street’ would look back on 1901 and ‘wonder how his ancestors could have existed with such a lack of the conveniences to which he himself is accustomed’. Wintle confidently predicted that wireless pocket telegraphy would mean that businessmen were never out of touch with the office, even when in the restaurant. The ‘electroscope’ would enable people ‘to watch a scene at a distance of hundreds of miles’. It scarcely needed to be said that this invention would be must-have technology for ‘busy men, who cannot attend the races’. In the field of war, Wintle anticipated that electric machine guns firing bullets at a rate of 3,000 a minute and mines detonated remotely by ‘Hertzian waves’ would revolutionize combat. 5Mobile phones, television, and radio-controlled bombs – Wintle’s predictions were not so far off the mark.

Whereas steam had driven the industrialized nineteenth century, it was clear by 1901 that electricity would be the energy of the twentieth. As Wintle put it, ‘electricity is the secret of progress’. 6Electric light was still something of a novelty. Albert Einstein was born in 1879, the year the incandescent light bulb was independently invented by Edison and Joseph Swan. In 1901, when a reporter visited Swan, he observed enviously that ‘electricity was much in evidence in Mr Swan’s own house; everywhere electric lights and bells’. 7

The Einstein family business, run by the young physicist’s father and uncle, was in the vanguard of the energy revolution, designing electricity supply systems and other electro-technologies. Based as they were in Munich, their firm had the honour of supplying the first electric lighting to that great Bavarian cultural event, the Oktoberfest , though Einstein himself took a dim view of beer-drinking. The Einsteins were not alone in trying to exploit the potential of this new power. More than five hundred inventions a week were registered at the British Patent Office in the first year of the new century.

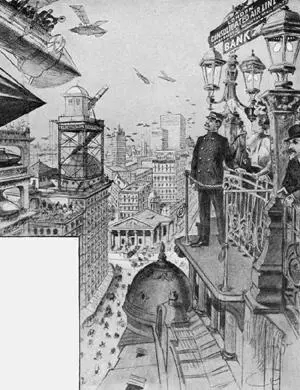

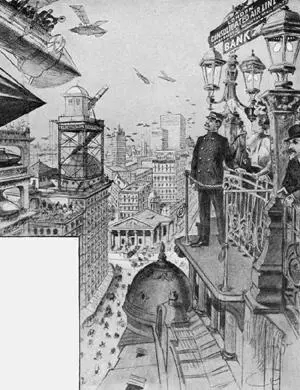

Illustration for W. J. Wintle’s 1901 article ‘Life in Our New Century’. The caption read: ‘The coming of the airship will necessitate roof stations. This is our artist’s suggestion for one at the Mansion House Corner, London.’

H. G. Wells’s story ‘Lord of the Dynamos’ (1895) depicts electricity as the power behind the modern mechanized metropolis. The electric dynamos in the story were futuristic gods whose power could be used for good or evil, like all scientific advances. In 1900 the historian Henry Adams toured the Exposition Universelle in Paris. For Adams, born in 1838, the dynamo was as mysterious as religion, an ‘occult mechanism’ beyond his comprehension. The connection between ‘steam and the electric current’ was no more graspable to him than that between the ‘Cross and the cathedral’. The forty-foot-high dynamos on show at this world fair in the French capital were the embodiment of ‘silent and infinite force’: ‘Among the thousand symbols of ultimate energy, the dynamo was not so human as some, but it was the most expressive.’ 8

The English aristocrat and novelist Edward Bulwer-Lytton was equally enthralled by electricity. In his 1871 Darwinist fantasy, The Coming Race , an American engineer stumbles across a subterranean civilization while exploring a deep mine. The beautiful yet ruthless people he discovers have created an aristocratic utopia using the power of an inexhaustible energy called vril. This energy flows through all matter and combines the properties of electricity and magnetism as well as mental energy. The people are called Vril-ya after their miraculous energy. It even gives them the ability to read minds and control inanimate matter at will.

The Vril-ya use this energy to give life to humanoid machines – robots. With their mechanical, vril-powered wings, these tall, sphinxlike beings are unmistakably angelic. This utopian society has abolished war, crime and envy. Yet, true to evolutionary principles, the Vril-ya are merciless towards neighbouring, less advanced peoples. They regard our surface-dwelling species as uncivilized and believe it is their destiny to eliminate us and take control of the earth.

Vril is a truly awe-inspiring energy source, and humans would have stood no chance on the battlefield, at least in the 1870s. The narrator describes ‘tubes’ of vril that could be fired at any object up to six hundred miles away. These missiles could, says the narrator, ‘reduce to ashes within a space of time too short for me to venture to specify it, a capital twice as vast as London’. The ‘terrible force of vril’ can also be directed using a ‘Vril Staff’ in the form of an energy beam. Its power reduces bodies to ‘a blackened, charred, smouldering mass… rapidly crumbling into dust and ashes’. 9

Читать дальше