Khrushchev, in short, was gambling that the Americans had put their money on the wrong weapons system.

• • •

“Well,” asked Khrushchev, “what else do you have to show us?” This was the moment Sergei Korolev had been waiting for; the moment he had prepared for ever since the day he was released from prison and sent to Germany to join Chertok and Glushko to uncover the secrets of Nazi missiles. (Chertok, alas, could not share in the triumph. He had been demoted from his post as NII-88 deputy director during one of Stalin’s anti-Semitic roundups. After Stalin’s death, Korolev eased Chertok back into a senior position at OKB-1, but his rank was not high enough to meet Presidium members.) Now NII-88’s most senior scientists stirred anxiously as Korolev prepared to unveil their collective masterpiece, the product of over a decade of research and millions of man-hours of dedicated work.

“We have seen the past and the present of Soviet rocketry,” said Korolev, leading his guests to a large double door, where a pair of crisply uniformed guards stood rigidly at attention. “This is the future.”

The doors swung dramatically open, and Sergei Khrushchev gasped. “I was amazed. I had never seen anything remotely like it, no one had,” he said, the excitement and wonder of that first glimpse still evident even after fifty years. Sergei and his father stepped into the top-secret inner room. The structure was brand-new, so spotless that everything shone, and its walls soared upward instead of lengthwise like the hangar they had just come from. These walls were constructed entirely of glass, and they had been painted white to allow light in but to keep prying eyes out. At the center of the gigantic atrium stood a rocket larger than Sergei Khrushchev had ever imagined. “It looked like the Kremlin tower,” he said.

Korolev stood aside and savored the moment. The rulers of the Soviet empire, among the most ruthless and powerful men on the planet, were frozen with awe. They had stopped dead in their tracks, reduced momentarily to the status of mere mortals. “Father later told me that he was simply numb, intimidated by the grandeur of such an object created by human hands,” Sergei recalled.

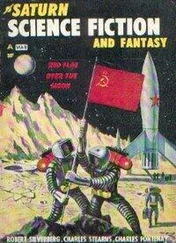

“The R-7,” announced Korolev with theatrical flair. The Presidium members recovered some of their composure and slowly circled the mammoth missile. In weight and mass it was ten times the size of the R-5, and almost twice as heavy as the Hindenburg Zeppelin, the largest aircraft ever built. Whereas the R-5 had one engine, the R-7 boasted five giant boosters that would consume 247 tons of fuel in four minutes. The nearly one million pounds of lift they generated could hurl the missile more than 5,000 miles at a speed of over 24,000 feet per second, four times faster and forty times farther than the original V-2.

The Presidium members drank this all in like a golden elixir. They poked their bald pates into the missile’s twenty burnished copper exhaust nozzles and craned their creaky old necks up at the inky black nose cone where the thermonuclear warhead would sit, a five-ton device that would have an explosive yield nearly one hundred times that of the atomic bomb the Americans had dropped on Hiroshima. The men of the Presidium shook their heads in wonder, whistled softly, and shot one another glances that brimmed with satisfaction. At last the Soviet Union would have its ultimate weapon, a rocket that could reach New York and Washington with the deadly force of all the combined ordnance dropped in the Second World War.

But try as they did, the Presidium members could not entirely fathom the full lethal potential of the R-7. Just how fast is 24,000 feet per second? Khrushchev tried to imagine.

“How long would it take to fly to Kiev?” he asked Korolev. When he was Stalin’s Ukrainian viceroy, Khrushchev had made the arduous three-hour air commute between Moscow and the Ukrainian capital several times a week in his old Douglass.

“Maybe a minute,” Korolev replied.

Khrushchev whistled appreciatively. Bulganin stroked his goatee. That meant the R-7 could reach the United States in less than half an hour. Even if the radar stations the Americans had built in Norway, Turkey, and Iran picked up the launch, they would not have enough time to react, to scramble the Strategic Air Command or evacuate their cities. The R-7 really could make all the difference, change the entire security dynamic—if it worked. And that would not be known until later that year, when testing could begin.

“Why is the rocket tapered in the middle?” Molotov asked, interrupting Khrushchev’s train of thought. The R-7 had a slightly hourglass-like shape because the four big boosters strapped around the central core flared out like a skirt. Korolev began to explain that the narrow midriff was necessary for the strapped-on engines to attach and jettison properly, but Khrushchev snapped impatiently: “Why do you ask such stupid questions? You don’t understand anything about these technical matters. Leave them to the experts.”

Molotov shrank back at the public rebuke but said nothing. There was a time when Khrushchev would never have dared to humiliate him so openly, when Khrushchev had fawned over him and genuinely admired him. But now the upstart was putting on airs, interfering in foreign affairs—even though he had never traveled abroad until after Stalin’s death. Once, when they had been coconspirators, Khrushchev had known his place. But now he was becoming impossible, an expert on everything. Behind his back Molotov called Khrushchev a “smalltime cattle dealer. Without a doubt a man of little culture. A cattle trader. A man who sells livestock.” Khrushchev, on the other hand, derided the old diplomat as a geriatric Stalinist relic. “Their relations had become tense,” Sergei Khrushchev recalled, “especially after the secret speech.”

Like Kaganovich, Molotov had been vehemently opposed to Khrushchev’s de-Stalinization program. For the foreign minister, there were external considerations. Fear of Stalin had been the glue that cemented the Eastern Bloc. After his death, rumblings of discontent had begun to ripple throughout the captive states of central Europe, particularly in Poland and Hungary. In Yugoslavia, Marshal Josip Broz Tito had become downright disrespectful, and Molotov had been furious that Khrushchev had not punished him. It set a bad precedent to be seen as so soft. And now that Khrushchev had denounced Stalin’s reign of terror, the Poles and Hungarians might also grow bolder. Khrushchev’s speech could be taken as a sign of weakness throughout the Soviet dominions, a reflection of waning resolve, a cue to rise up. Khrushchev, the novice, didn’t understand any of these things; he had no comprehension of the forces he might have unleashed. His pigheaded ignorance could bring down the whole empire.

Molotov, of course, said none of this publicly. He was too seasoned a Kremlin intriguer to make that mistake. Publicly he recanted his opposition to appeasing Tito, saying, “I consider the Presidium has correctly pointed out the error of my position,” and joined Kaganovich in praising Khrushchev on his insightful initiatives. “Comrade Khrushchev carries out his work… intensively, steadfastly, actively and enterprisingly, as befits a Leninist Bolshevik,” he had said only a few months earlier. But privately, Kaganovich and Molotov were already whispering in Bulganin’s malevolent ear. Now was not yet the time. Like the butcher Beria before him, the cattle salesman would get his comeuppance soon enough. With luck he might not even live to see the R-7 fly.

• • •

“I would like you to know about still another project,” Korolev said quickly, as the Presidium delegation was about to leave. For the first time a hint of hesitation had crept into the Chief Designer’s normally self-confident tone, and his words had gushed out in a torrent of pent-up anxiety.

Читать дальше