For nearly a minute no one spoke. Khrushchev finally broke the silence. Which countries were in its range? he wanted to know. His son recorded the scene: “Korolev walked over to a map of Europe, which was hanging on a special stand. It looked just like the ones we had had in school, except that this one had arcs of intersecting circles against the blue background of the Atlantic Ocean. Thin radii drawn with India ink stretched to [the Soviet bloc’s] western borders, to the frontier of East Germany. In the upper right-hand corner of the map there was a calligraphic inscription: ‘Highly classified. Of special importance.’ Slightly below that was Copy Number—I don’t remember the number, but it was no higher than three.”

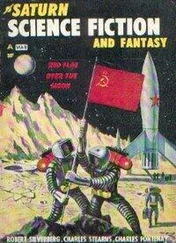

The map showed that the R-5 could strike every nation in Europe, except Spain and Portugal, which were still out of range. A murmur of satisfaction rose from the Presidium members. “Excellent,” said Khrushchev. “Until recently we couldn’t even dream of such a thing. But the appetite grows by what it feeds on. Comrade Korolev, isn’t it possible to extend the rocket’s range?”

No, the Chief Designer replied flatly, a new missile would be required. Khrushchev and the others seemed disappointed. But Korolev appeared unperturbed; his authority was already well established within Kremlin circles. The delegation remained rooted in front of the map for some time, contemplating Armageddon. “Father stared piercingly at it,” Sergei Khrushchev recalled.

“How many warheads would be needed to destroy England?” the party leader finally asked. “Have you calculated that?”

Dmitri Ustinov, the armaments minister, fielded the question. “Five. A few more for France—seven or nine, depending on the choice of targets.”

Only five? Khrushchev seemed skeptical. The British had withstood a daily barrage of V-2s. They had shrugged off the Junker bombers during the Blitz, displayed a tenacity that even Stalin had praised. But now Great Britain was America’s closest ally; it would have to be taken out first.

“Five would be enough to crush defenses and disrupt communications and transportation, not to mention the destruction of major cities,” Ustinov explained. His tone, Sergei Khrushchev remembered, “did not allow for even a shadow of a doubt.”

“Terrible,” said Khrushchev, trailing off in thought. Five flicks of a switch to break the will of a nation like Britain. Astonishing. Cost-effective, too.

• • •

It was not only the search for a new weapon to counter American air superiority that had brought Khrushchev to Korolev’s design bureau. He was also looking for ways to save money because, unlike the booming American economy, Soviet central planning was in trouble. The years of rapid growth after the war, when entire cities and industries had been rebuilt from rubble, were over by the mid-1950s. Most Western European nations had made remarkable recoveries by then, due in part to the Marshall Plan. But the command economies of the Eastern bloc had spurned American financial aid and were now beginning to suffer from a crisis of inefficiency. Put simply, Soviet central planning was suffering from the law of diminishing returns. No matter how many rubles the Russians sank into their wobbly industries, they were getting a smaller and smaller return on their investment. And the problem was only going to get worse over time.

For Khrushchev, the economic slowdown came just as his treasury faced the twin challenge of meeting the raised American threat and rising consumer demands at home. After years of sacrifice, first during the war and then during reconstruction, Soviet citizens were beginning to yearn for a higher standard of living. Encouraged in part by a slew of lighthearted films and musicals after Stalin’s death that featured fashionable clothes, fast cars, and the joys of shopping, Soviet citizens had embraced this new material slant on life. Khrushchev had approved the cinematic thaw and the departure from the austere militarist offerings of Stalinist directors because he understood that he could not rule by fear alone. Stalin had shrewdly substituted a diet of national pride and terror for material well-being that had given his subjects comfort in the notion that while they were frightened and poor, they were building a great empire and a better tomorrow. Khrushchev preferred the carrot to Stalin’s stick. Parades were not enough. People had to have tangible rewards from the socialist miracle touted by the new propaganda films.

To bring his movies more in line with reality, Khrushchev needed to free up hundreds of billions of rubles to pay for housing projects, to recapitalize decrepit automobile factories, and to finance agricultural reforms that would put food on people’s tables. As things stood, the Soviet Union could barely feed itself. Yields were so low that in 1953 per capita grain production had fallen to 1913 levels. All told, the USSR’s muddy collective farms were producing less food in the early 1950s than they had in 1940. If the trend continued, the Soviet Union would starve.

To reverse the decline, Khrushchev had embarked on a hugely ambitious and controversial program to develop 80 million acres of virgin steppe in central Asia that was intended to increase agricultural production by 50 percent. Molotov, in particular, had vehemently opposed the plan, which required relocating three hundred thousand farmworkers and fifty thousand tractors to cultivate the raw fields in Kazakhstan and southern Siberia. It was far too expensive, Molotov argued, and the climate was too harsh. But Khrushchev had overruled him; the money, he said, would be found somewhere, trimmed from the fat of various other budget allocations.

Military expenditures ate up between 14 and 20 percent of the Soviet economy, compared to 9 percent for the United States, whose economy was much larger. And yet, despite the large outlays, the Soviet armed forces could not adequately address the new American jet-bomber threat. The Red Army had more than 3.5 million men under arms, but they were useless against B-47s carrying nuclear bombs. What’s more, they were expensive; soldiers had to be clothed, fed, housed, and provided with costly trucks, tanks, and artillery whose role in a nuclear standoff was of limited or no value. Khrushchev could try to compete with the Americans by bulking up his aging fleet of World War II-era bombers, but it was becoming clear that he could not keep pace with the U.S. Air Force. Even if Khrushchev ramped up spending, he could not hope to match the new B-52 superbomber that Boeing was beginning to mass-produce. In heavy aviation, the Soviet Union had simply fallen too far behind to make the investment worthwhile.

In the high-stakes arms race, Khrushchev was a pauper playing at a rich’s man table. Given the vast financial gulf between America and the Soviet Union, he had to marshal his resources more carefully than Eisenhower, and he saw that missiles were the cheapest, most cost-effective way to stay in the game. Their costs were mostly up-front, in research and development. And Khrushchev felt that he would not need to produce them in significant numbers. That hadn’t been the case in World War II. Hitler, after all, had bet the Reich on the V-2, built thousands of them, and lost. But that was before the atomic age. Nuclear warheads dramatically changed the equation. Now you could defeat England with only five rockets and keep America at bay with a few dozen more. From a financial point of view, focusing on missiles made more sense than maintaining a huge standing army or sinking money into giant bomber fleets that rockets would soon render obsolete anyway.

And so Khrushchev was betting the farm on Korolev. He had slashed spending on conventional forces to free up funds for foodstuffs and housing, while he hoped that the Chief Designer’s missiles would provide the USSR with a shield against American bombers. Just how big a wager he was placing would stun the CIA, which in a 1958 report underscored “the striking re-allocation of expenditures within the [Soviet military] mission structure. The most dramatic examples are the 34% decline in expenditures for the ground mission, and the 127% increase for the strategic attack mission…. Increasing expenditures on strategic attack reflect the replacement of the manned bomber by long range missiles.”

Читать дальше