This was long before the time when the Roman legion was a highly trained and incredibly flexible military machine. The massive Roman column could do nothing but push harder, hoping to literally fight their way out by breaking through the Gauls. But at just the wrong time for it to happen, the Carthaginian armored horsemen returned from chasing off the Roman cavalry and slammed into the back of the thickly packed Romans.

The most experienced Roman soldiers made up the last lines of the attacking column, and they turned about, met the Carthaginian charge, and held it. But to do this they had to stop moving and plant their pikes facing the rear, away from where the Romans were attacking. This brought the entire Roman army to a dead stop, and the operative word there is dead . Packed fifty men deep to ensure they broke the center, this awkward Roman formation, which resembled a phalanx without the spears, meant that most of the Roman soldiers could not fight until the men in front of them had been killed. Since most of the men were now totally surrounded by the Carthaginian army, all they could do was wait to die. And 40,000 did, though Varro, who had caused the battle to be fought, escaped and even distinguished himself when he reorganized the survivors. The Carthaginian losses were in the hundreds, mostly expendable Gauls.

Cannae is often considered one of the most one-sided victories in history. All the more amazing as it came against a Roman army that would go on in the next four centuries to conquer the Mediterranean world. But the battle was really lost because of where it was fought, which gave every advantage to the brilliant Hannibal. A mistake that was forced on Paullus by a system that put an inexperienced politician in command of the entire Roman army at just the wrong time.

An Offer They Should Not Have Refused

204 BCE

In 204 BCE, the war with Rome was not going well for Carthage. The city had lost its final holdings on Sicily and other islands. Spain, the merchant city’s main source of mercenary armies, had fallen. Now Gnaeus Cornelius Scipio, the same Roman commander who had defeated their armies in Spain, had landed a large Roman army near the city itself. Making things worse was that one of the Carthaginians’ closest allies in Africa, Massinissa, had changed sides and had led his experienced cavalry to join the Romans. He brought with him several thousand horsemen, nicely rounding out the Roman order of battle.

Carthage gathered an army and called on its remaining major ally, Syphax, and his army and moved to defeat Scipio. But in a night attack, the smaller Roman army and its ally routed and then slaughtered the camped Carthaginians. There was only one response left for the great merchant city that had been fighting Rome for more than a decade. They recalled Hannibal and the last army they had left from Italy.

Hannibal Barca and about 15,000 of his veterans slipped past the Roman fleet and soon were in Carthage. At this point, Scipio made the city a proposal. He was under pressure from an untrusting and jealous Senate and wanted the war over before they could recall him to Rome. So Scipio made the city a very generous offer that would not only have allowed Carthage to keep its merchant fleet, a major source of the city’s wealth, but would also have left it a large degree of independence and even a small fleet of warships. Carthage would not again be a military threat to Rome, but it could remain an economic powerhouse, wealthy from trade and manufacturing.

The city of Carthage was now at war with a Rome that controlled the entire western Mediterranean. They no longer had their main source of soldiers, their manpower was limited, and one of their key allies had changed sides. Even if they defeated Scipio, they would not, and probably could not, win the war. Rome, which had proven amazingly resilient, would simply send another army and then another until they finally won. But the return of Hannibal and his veterans gave the people of Carthage hope. The city’s leaders flatly refused the Roman commander’s offer.

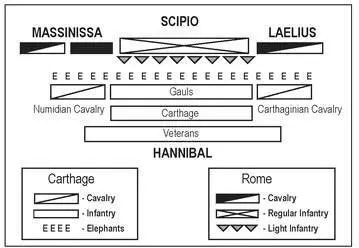

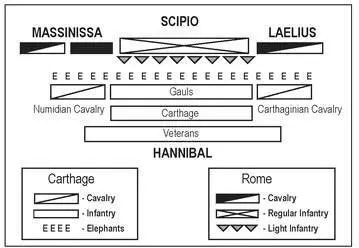

A few days later Hannibal and Scipio’s armies faced each other near Carthage. Hannibal’s army had elephants and his core of veterans. The Roman army had its flexible and well-trained smaller units and superior cavalry.

The Battle of Zama

Hannibal’s Carthaginians were formed into three lines each behind the other. The legions were in long columns made up of maniples, numbering between 100 to 180 men. They lined up not shoulder to shoulder but behind one another in long columns. This was unusual because the legion normally deployed in a checkerboard formation that allowed for maximum maneuverability or in a line to allow the most soldiers to fight for the frontage.

The battle began when Hannibal ordered a charge by the war elephants that were spread all across the Carthaginian front. It was hoped the large beasts would disrupt the Roman formations and scatter its cavalry. But like most animals, these elephants ran along the line of least resistance. Those that were not frightened or driven away by javelins simply hurried down the open spaces between the columns while their riders were fired at from both sides. Worse for the Carthaginians was that the elephants, charging the Roman right, were actually turned around by the noise and pain. Instead of disrupting the Roman cavalry, they slammed into their own Numidian horsemen, who were protecting the Carthaginian left flank. Observing this happen, Massinissa charged his larger cavalry force and infantry against the disorganized Numidian horsemen. The Numidians broke and ran almost immediately. Seeing this, the Roman horsemen on the other side of the battle charged as well. There was a violent melee and then the Carthaginian cavalry abandoned Hannibal’s right flank as well. The Carthaginian flanks were open to attack, but since both Roman forces followed the enemy horses off the field in pursuit, these flank victories did not determine the battle. For a while, the Roman successes simply left the field to the infantry. This was good news for Carthage because they had 45,000 soldiers to Rome’s 34,000.

Hannibal ordered his front line to charge Scipio’s Romans, who, with the threat of elephants gone, had re-formed into a solid front. That first line consisted of mostly Gauls: individually brave but not skilled at fighting in a unit. They smashed into the Romans, and the fighting degenerated into man-to-man combat. They were doing what Hannibal hoped, breaking up the solid Roman front.

For some reason Hannibal’s second line, made up of newly trained Carthaginians, failed to advance and take advantage of the Gauls’ attack. Seeing they were not being supported but were left to die in front of the Romans, the Gauls turned and fled. But the unmoving line of Carthaginians refused to open to let them pass. Needless to say, the Gauls now were sure they had been betrayed and began attacking Hannibal’s second line. The two Carthaginian formations were still fighting when the front of the Roman army, Scipio’s hastati (a class of infantry), slammed into them both. When the second line of Romans, the principes , joined in the fighting, the surviving Gauls and Carthaginians of the second line were both routed.

The retreating Carthaginian second line then ran directly toward the last of Hannibal’s formations. This was a line formed by the veterans who had come back from Italy with him. They knew that if they broke formation to let the fleeing Carthaginians through, the Romans advancing just behind the fugitives would tear their line apart. So, they too held solid against their own retreating soldiers. For a second time, one of Hannibal’s lines fought against the other as the Romans advanced behind it.

Читать дальше