That delay of twenty-seven days to retreat, for no other reason than superstition, changed the entire Peloponnesian War. Athens never recovered from the loss of more than 12,000 hoplites and twice as many rowers and light infantry. Sparta proved unable to replace Athens as the politically dominant city in Greece. The military dictatorship had lost too many of its highly trained hoplites in the war as well. Rather than a strong central leadership, such as Athens had provided for Greece before the war with the Delian League, the Greek world was once more split owing to jealousy and constant bickering among the city-states. This left the area vulnerable to the eventual conquest of one Philip of Macedonia.

Athens might have survived Alcibiades’ mistake in starting the invasion if it had not been for Nicias’ miscalculation. Without the first mistake caused by the ego of Alcibiades, Athens likely would have continued to win the Peloponnesian War and maintained its dominance of Greece. Without Nicias superstitiously forcing that last-minute, highly risky delay, the army and fleet would not have been lost and the mistake of attacking Syracuse would have embarrassed, but not crippled, the city-state. Had Athens not been drastically weakened on Sicily the world of the ancient Mediterranean and our world today would have been totally different.

If Athens had stayed strong, there would have been no Macedonian domination under Philip and so no Alexander the Great. Persia, playing a key role in Greek politics, might well have remained an intact Eastern empire for centuries longer. Instead of becoming the dominant culture in all the lands from Egypt to Babylon, Greek culture and democracy might well be a footnote rather than a force in history. That their city’s defeat and collapse led to the ideals of democracy and Greek values later being spread to all of Europe and Asia would likely be of little consolation to the people of Athens, who paid a very high price for both Alcibiades’ and Nicias’ mistakes.

How to Lose an Empire

331 BCE

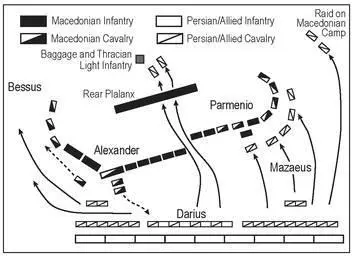

In 331 BCE, Emperor Darius III made a decision during the Battle of Gaugamela (fought near present-day Irbīl in northern Iraq). His army greatly outnumbered his opponent’s, and he was fighting where and almost when he wanted. At the point Darius lost it all with one bad decision, the Persian emperor still had plenty of uncommitted troops and the other side was on their last reserves. Almost everything still favored Darius, except that he had an immediate and personal problem. The opposing commander was leading a charge directly at the king of kings, and that commander was Alexander of Macedon.

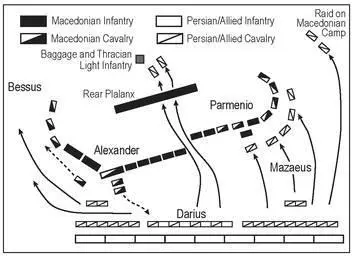

Alexander’s charge was a grave threat to Darius, but at that point, the rest of the fighting was actually going well for the Persians. On the Persian right, they were pressing back the Greeks, who were commanded by Alexander’s top general, Parmenion. The Persian center was only lightly engaged except directly in front of the throne from which Darius was commanding the battle. There the elite companion cavalry, and a number of the best Macedonian phalanxes, had reversed a march across the Persian front and were cutting their way toward the emperor. Virtually no Greek forces faced the much larger Persian army’s left.

A few years earlier, in the Battle of Issus, Darius had fled when the battle seemed lost. He had hurried back to Babylon with no ill effect on his control of the heart of his empire. There he raised a newer and much larger army. He intended to use that superior army to defeat Alexander in the current fight. Darius’ survival was politically important. Being a Persian emperor was a highly personal position; for Alexander to claim the throne and be recognized by the rest of the empire, he had to capture or kill Darius III. Perhaps the fact that he fled at Issus with no problems encouraged the emperor to think he could flee again without it being a disaster. Or maybe, although he was a most capable leader and politician, Darius III was just a coward when physically threatened. Whatever the logic or reason, before the Macedonians even got close to his throne, the Persian emperor got into a chariot and fled the battle.

There were more Persian infantry covering Darius’ retreat than there were phalangists, the heavy infantry who carried the thirteen-plus-foot-long metal-tipped pikes known as sarissas and who endured the burden of the “push” that was the basis of the fighting in Alexander’s Macedonian army. And Parmenion was in the process of being mauled by far-superior Persian infantry and horsemen, and almost half the Macedonian army was in danger of being destroyed. So decimated were Parmenion’s troops that Alexander had to use his entire attack force to assist the hard-pressed left side of his army. This command decision was made all the more difficult because Alexander knew that all he had to do was eliminate the king of kings to win a clear victory. Fortunately, since the leadership of Persia was a very personal thing, when word got out that Darius III had run away, the rest of his army either backed off or fled outright.

The Battle of Gaugamela

By almost any standard, Darius was not losing the battle when he hurried away. He still had plenty of uncommitted forces that could have been called on, including a large number of cavalry. If he simply moved to another location and had his army continue to fight, he might even have won. Certainly he would have punished the Macedonian army, which was already at the end of a very long supply line with few reinforcements expected, and at the point where it could not effectively occupy the capital. Alexander the Great might today instead be known as the Alexander who overreached himself and failed. But for whatever reason or personal flaw, Darius did run and run hard. He was still fleeing when he died weeks later at the hands of his own generals. Because he abandoned the Battle of Gaugamela, the Persian threat to Greek culture was ended, and the world as we know it, democracy, heroes, and all, came to be.

The Death of Alexander the Great

323 BCE

Of all the historical figures to have the identifier “the Great” tagged onto their names, Alexander the Great is one who really lived up to the title. No other leader has been able to cross cultural boundaries or capture the imaginations of world leaders like he has done. He has stood the test of time. His tactics are still taught in military academies all over the world. He has become the measuring stick by which all others have compared themselves. When Julius Caesar came across a statue of Alexander, he fell at its feet and wept, marking how the great conqueror had accomplished more by his death at the age of thirty-two than Caesar himself had at the time of viewing the statue. Why does Alexander still have this immortal grip on us? If he was so great, why did his empire collapse? For one simple reason… Alexander did not name a successor. The vast empire that he created fell apart because he was unwilling to pass on the gauntlet.

Philip II of Macedonia had his hands full when his wife Olympias gave birth to a son in 356 BCE. The overzealous mother named her son Alexander, meaning “the lion.” Most mothers believe their firstborn sons will rise to greatness, but Olympias believed her son was the son of a god. Philip himself doubted the child’s lineage when he supposedly spied his wife in the embrace of a serpent, a creature of which Zeus often took the form. Philip had to be sure. He sent an emissary to the Oracle of Apollo at Delphi. The oracle answered that Zeus should be revered above all other gods. She also said that Philip would lose the eye through which he saw his wife with the serpent. Two years later, Philip lost his eye.

Читать дальше