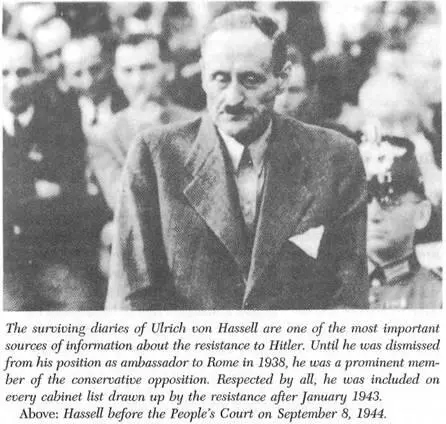

The futility of this gesture, on which he had apparently based great hopes, was made clear to him scarcely four weeks after his incarceration at Gestapo headquarters on Prinz-Albrecht-Strasse. On September 8 he stood before the People’s Court with Ulrich von Hassell, Josef Wirmer, lawyer Paul Lejeune-Jung, and Wilhelm Leuschner. Their trials proceeded like all the rest, with a raving, wildly gesticulating Freisler constantly interrupting and refusing to allow any of the accused to explain their motives. In the end Goerdeler was condemned as a “traitor through and through,… a cowardly, disreputable traitor, consumed with ambition, and a political spy in wartime.” While Wirmer, Lejeune-Jung, and Hassell were executed that same day and Leuschner was dispatched two weeks later, Goerdeler was kept alive for almost five months. He was probably spared so that further information could be extracted from him and so that his skills as a master administrator could be exploited for drawing up plans for reform and reconstruction after the war. The decisive factor in the delay, however, was presumably Himmler’s desire to have Goerdeler as a negotiator in the event that his insane scheme of making contact with the enemy behind Hitler’s back succeeded. This supposition is supported by the fact that Popitz’s life was also spared for some time, even though he had been sentenced to die on October 3. 22

Goerdeler hoped that his date with the executioner would be delayed until the war had ended, saving him and his fellow prisoners. Meanwhile, however, the Allied advance into central Germany was stalled, and Justice Minister Otto Thierack began asking more and more pointed questions as to why Goerdeler and Popitz were still alive. Like so many of his previous fantasies, Goerdeler’s last hope finally burst on the afternoon of February 2, 1945, when bellowing SS men barged into his cell and led him away.

Gerhard Ritter has painted a profound and compelling portrait of Goerdeler as someone whose very relentlessness in the struggle against Hitler was symptomatic of a lack of realism. Arrested as a member of the Freiburg group of professors, Ritter found himself face to face with Goerdeler in prison in January 1945: “A suddenly aged man stood before me,” Ritter later recounted, “chained hand and foot and wearing the same light summer clothing-now shabby and collarless-in which he had been arrested.” What shook Ritter most, however, were Goerdeler’s eyes. Always so luminous in the past, they had now become “the eyes of a blind man.” 23

* * *

On September 15, 1944, Ernst Kaltenbrunner reported that the investigations had been largely completed and that no further revelations could be expected. Then, just eight days later, papers fell into the hands of Reich Security Headquarters that proved him wrong. Lieutenant Colonel Werner Schrader, a close confidant of Hans Oster’s at Military Intelligence, had committed suicide, and his driver, feeling despondent and abandoned, approached police inspector Franz Xaver Sonderegger and described to him a bundle of papers that had been deposited in the Prussian State Bank in 1942 and later taken to Zossen, where they were stored in a safe. His curiosity aroused, Sonderegger went to Zossen and opened the safe. What he found were the materials that Beck, Oster, and Halder had produced for the coup attempt in the late 1930s and that Hans von Dohnanyi had gathered together: minutes of meetings, plans for military operations, addresses, notes on the Blomberg and Fritsch affairs, loose sheets of paper-all of it carefully filed. There were even a few pages from the long-sought diaries of Admiral Canaris.

The discovery brought to light the activities of Halder, Brauchitsch, Thomas, Nebe, and others, but what was much more devastating to the regime was the sudden realization once again that the assumption underlying the entire investigation was false. The conspiracy of July 20 was plainly not the work of a few disgruntled, resentful, or exhausted officers, unhappy with the reversal in the tide of war. Quite to the contrary, the roots of the conspiracy reached as far back as 1938, the highest echelons of the Wehrmacht were involved, and the motives of the conspirators were much more complex than anyone had suspected. Kaltenbrunner’s next report spoke of the conspirators’ desire to prevent the outbreak of war, their widespread criticism of the “handling of the Jewish question,” the Nazis’ policy toward the churches, and the generally “harmful influence” of Himmler and the Gestapo. 24Hitler was so alarmed that he ordered that none of the documents was to be entered into evidence in the trials before the People’s Court without his specific approval. He also insisted that the investigation of the new revelations be strictly separate and that the arrest of General Halder and his incarceration on Prinz-Albrecht-Strasse be kept secret from all the other prisoners. 25

The Nazis’ belief in the unity of Volk and Führer could not survive the Zossen documents and the information they revealed. As one high official in the Ministry of Justice commented in desperation, “We are being engulfed by July 20. We are no longer masters of the situation.” 26Hitler decided to postpone the trials connected with the newly uncovered conspiracy, and when an American bombing raid destroyed part of Gestapo headquarters he ordered the prisoners implicated in the conspiracy transferred to Buchenwald and then to Flossenbürg in the Upper Palatinate region. It is possible that he even considered sweeping the entire affair under the rug.

On April 4, 1945, the bulk of Canaris’s fabled diaries turned up by accident, once again in Zossen. Kaltenbrunner thought the discovery so important that he personally delivered the black notebooks to the Reich Chancellery the very next day. Immersing himself in the revelations they contained, Hitler grew increasingly convinced that his great mission, now under threat from all sides, had been sabotaged from the outset by intrigue, false oaths, deception, and betrayal from within. His anger, hatred, and frustration exploded in a volcanic outburst, which concluded with a terse instruction for the commander of the SS unit responsible for his personal safety, Hans Rattenhuber: “Destroy the conspirators!” 27

In a farcical procedure, Kaltenbrunner immediately convened two SS kangaroo courts, though they lacked jurisdiction and therefore any veneer of the legality they were meant to display. One court traveled to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp, where Dohnanyi was being held. In order to escape the tortures of his interrogators, he had intentionally infected himself with diptheria bacilli and was still suffering the effects: severe heart problems, frequent cramping, and paralysis. Only semiconscious, he was carried before his judges on a stretcher and, without further ado, condemned to hang. There was not even a written record of the proceedings, though this was strictly required by German law.

Events transpired similarly at Flossenbürg, where, two days later, on April 8, 1945, the second kangaroo court condemned Canaris, Osier, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Military Intelligence captain Ludwig Gehre, and army judge Karl Sack. While Canaris still sought a way out during the proceedings, Oster reportedly declared, “I can only say what I know. I’m no liar,” and defiantly owned up to all that he had done. In the end all the accused were condemned to die. That evening Canaris tapped out a final message to the prisoner in the next cell, a Danish secret service officer: “My days are done. Was not a traitor.” 28

As the skies began to lighten at dawn the next day, the executions began. The victims were taken to a bathing cubicle, where they were forced to strip; then, one by one, they were led naked across the courtyard to the gallows. Hooks had been attached to the rafters of an open wooden structure. The condemned men were ordered to climb a few steps, a noose was placed around their necks, and the steps were kicked aside.

Читать дальше

![Traudl Junge - Hitler's Last Secretary - A Firsthand Account of Life with Hitler [aka Until the Final Hour]](/books/416681/traudl-junge-hitler-s-last-secretary-a-firsthand-thumb.webp)