On the stacks of clothing left behind were found the books that the victims had been reading when the end came: on Bonheoffer’s, the Bible and a volume of Goethe’s works; on Canaris’s, Kaiser Frederick the Second by Ernst Kantorowicz. Although Josef Müller had traveled to Rome on a number of occasions at Oster’s behest and was also incarcerated in Flossenbürg, for some inexplicable reason he was not tried and condemned with his fellow conspirators. Late that morning he learned from an English prisoner that the bodies of his friends were already being cremated on a pyre behind the camp jail. “Particles floated through the air,” he later recalled, “swirling through the bars of my cell…little bits of human flesh.” Two days later the rumble of the approaching front could be heard in the distance. 29

* * *

The more hopeless Germany’s military prospects became, the more summary and arbitrary was the regime’s great reckoning with its domestic opponents, as the courts reached out to punish people only marginally involved in the uprising. In early October 1944 Martin Bormann took it upon himself to remind Hitler that Erwin Rommel, on a visit to Führer headquarters near Margival the previous June, had flatly contradicted Hitler and had subsequently urged him to end the war. Kluge’s suicide cast further, though never proven, suspicions on Rommel, whose enormous popularity with the German people only made Hitler more jealous and wary. On October 7, while he was still convalescing at home from the serious war wounds he had suffered, Rommel received orders to present himself in Berlin three days later. On the advice of his doctors, he replied that he was unable tomake the journey and asked to send an officer instead. In response, Generals Ernst Maisel and Wilhelm Burgdorf, both members of the military “court of honor,” were dispatched to Rommel’s residence in Herrlingen near Ulm, where, on October 14, they presented him with an ultimatum: either he took poison and received a state funeral or he would be brought before the People’s Court. While this discussion took place, SS units surrounded the village. After Hitler’s emissaries left the house Rommel told his wife that he did not shrink from the prospect of a trial but was certain he would never reach Berlin alive. He was also concerned about the consequences for his family if he opted for a trial. And so Rommel decided to take the poison. “I’ll be dead in a quarter of an hour,” he said before heading out the door to where the two generals were waiting. It was shortly after one o’clock in the afternoon.

About twenty minutes later Maisel and Burgdorf delivered the corpse to a military hospital in Ulm. When the head physician wanted to conduct an autopsy, Burgdorf warned, “Don’t touch the body. Everything is being taken care of from Berlin.” Wilhelm Keitel later said that though Hitler himself first suggested doing away with Rommel, the Fuhrer never revealed the real reasons, even to his closest confidants, and insisted to Goring, Jodl, and Donitz that the field marshal had died of natural causes. 30

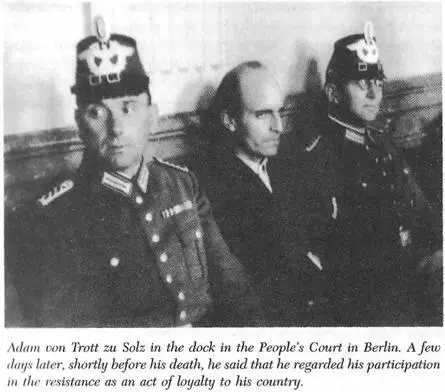

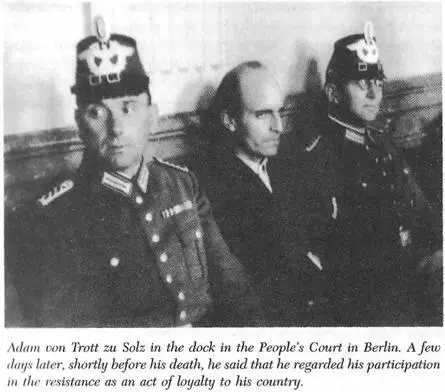

Meanwhile the political trials had continued, at first at a pace of one a week and later about one every two weeks. On August 15, 1944, Count Helldorf, Hayessen, Hans-Bernd Haeften, and Adam Trott were sentenced to death; on August 21, Thiele, Colonel Jäger, and Schwerin von Schwanenfeld; the next week, Stülpnagel, Hofacker, Linstow, and Finckh. Soon thereafter came Thüngen, Langbehn, Jessen, Meichssner, and General Herfurth (despite his refusal to help on the day of the coup attempt). On October 20, Julius Leber and Adolf Reichwein were condemned, then Captain Hermann Kaiser, General Lindemann, Theodor Haubach, and many others.

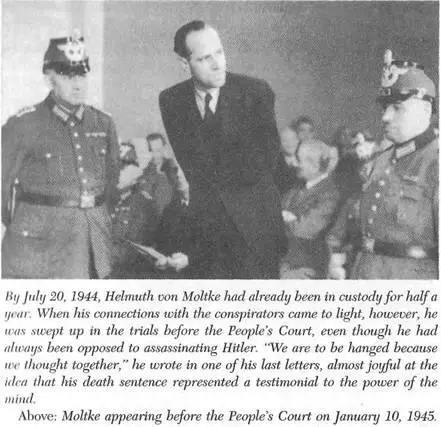

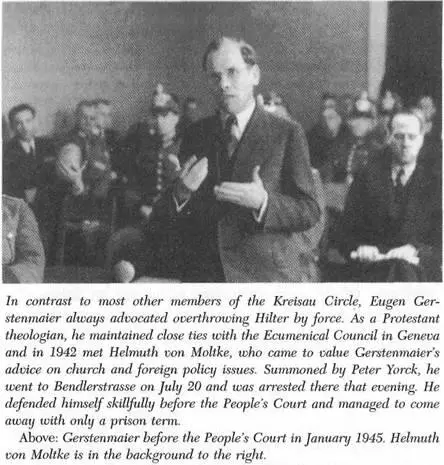

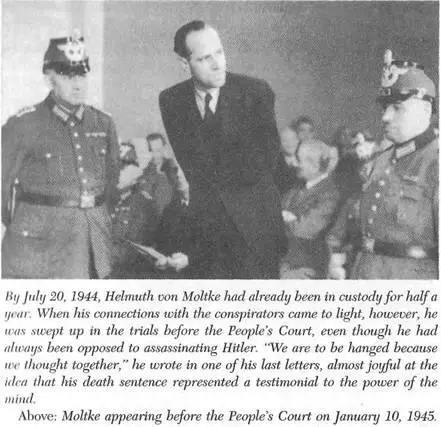

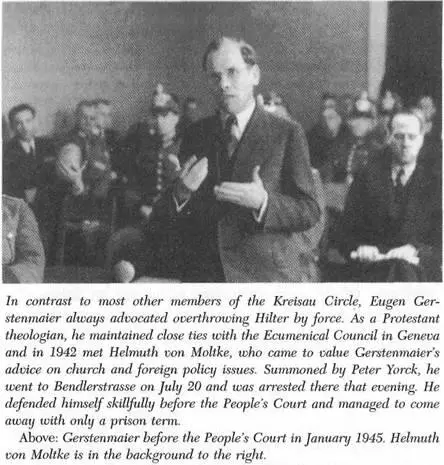

Moltke was tried on January 9-10, 1945, along with Alfred Delp, Eugen Gerstenmaier, and a few other friends from the Kreisau Circle. Moltke’s connection with the events of July 20 was actually more circumstantial than direct, though he had associated with a number of the rebels. Immediately after the attempted assassination and coup he remarked, “If I had been free, this would not have happened,” a reference to the fact that he had already been arrested by that time. At his trial he continued to insist that he was opposed to any acts of violence.

Despite his negligible role in the coup, Moltke exemplifies better perhaps than any other opposition figure the deep ambivalence of the German resistance. The records of his trial have been lost, like so many others, but on January 10 and 11, shortly after his trial, he wrote two letters to his wife that were spirited out of his cell by Poelchau, the chaplain. They contain far more than just personal comments. An entire intellectual climate emerges in the love of philosophizing, the distaste for practical action, and the religiously inspired joy at the prospect of death. As one of the early chroniclers of the German resistance commented, Moltke’s letters can only be read “with horror and admiration.” 31

The letters begin with an extensive description of his trial, at which Kreisler sought to portray not Goerdeler but the Kreisauers—“these young men”—as the actual “engine” behind the coup. Moltke emphasizes repeatedly that he not only agreed with that assessment but was absolutely delighted by Freisler’s decision to drop all specific allegations related to practical preparations for the coup in order to focus on the real crimes: “defeatist” thought and adherence to the Christian and ethical principles to which Moltke and his friends wanted society to return.

“Ultimately,” says Moltke in the first of these long letters, “this concentration on the religious aspect corresponds with the inner nature of things and shows that Freisler is a good political judge after all. It gives us the inestimable advantage of being killed for something that (a) we really have done and (b) is worthwhile.” He continues, “It is established that we never wanted to use force; it is established that we did not make a single attempt to organize anything, did not promise a single person a future post-though the indictment said otherwise All we did was think-and really only Delp, Gerstenmaier, and I…And it is before the thoughts of these three isolated men, the mere thoughts, that National Socialism now so trembles that it wants to exterminate everything that is infected by them. If that isn’t a compliment of the highest order! After this trial we are free of all the Goerdeler mess; we are free of all practical questions. We are to be hanged because we thought together. Freisler is right, right a thousand times over. If we are to die, then let it be for this… . Long live Freisler!”

These few lines distill both what was memorable about the German resistance but what, at the same time, constituted its greatest weakness and the most compelling reason for its failure. The “Goerdeler mess” about which Moltke writes so disparagingly was in fact nothing other than a practical relation to the world, to people, and to the forces at work-in a word, to reality. Virtually all the opposition groups, though some more than others, liked to think of themselves as above the concerns of the grimy everyday world, and that attitude seriously compromised their ability to accomplish anything, especially as the Nazis did not respect the distinction but viewed thought and action as one. On the final judgment against Moltke one contemporary who had read the letters commented curtly, “He did more than just think.”

Читать дальше

![Traudl Junge - Hitler's Last Secretary - A Firsthand Account of Life with Hitler [aka Until the Final Hour]](/books/416681/traudl-junge-hitler-s-last-secretary-a-firsthand-thumb.webp)