Time and again, fugitives sought by the police turned themselves in out of a feeling that can best be described as part pride and part exhaustion. They were no longer willing or able to hide out or to continue the duplicitous life they had led for far too long, at the cost, they believed, of their self-respect. Ulrich von Hassell left his home in Havana and traveled to Berlin by a circuitous route, making many stops. For a few days he roamed restlessly through the streets of the capital, then went to his desk and waited calmly for the Gestapo to arrive. Theodor Steltzer, who was already in Norway, refused to flee across the border to Sweden, returning instead to Berlin, where he acted on his belief that a Christian cannot tell a lie, even to a Gestapo interrogator or before the People’s Court. 5

The motivation behind these and many other unrealistic if honorable gestures was certainly the expectation that the impending trials could be used as a forum for denouncing the Nazis. As the curtains fell on their lives, these brave men hoped for one last chance to expose the true nature of the regime, much as some of them had fervently hoped to do in criminal proceedings against Hitler. The illusion that they would be allowed to speak their minds freely at their trials was soon shattered, however, as was the belief, cherished primarily by the military men, that every legal formality would be observed and that they would be treated in a manner befitting their standing in society.

Although the investigators found themselves groping in the dark at first over the next few months, they succeeded in arresting some six hundred suspects beyond those immediately implicated in the plot. A second wave of arrests in mid-August, known as Operation Thunderstorm, put five thousand putative opponents of the regime behind bars; most of these people had been connected to various political parties and organizations in the Weimar Republic. Again, even when under interrogation, some of the accused strove more to demonstrate the high moral principle behind their actions than to save their lives, so that the head of the special investigatory commission was soon able to say that “the manly attitude of the idealists immediately shed some light in the darkness.” 6

Although much of this courageous and self-sacrificing spirit may seem naive, it was perhaps the only defense to which the regime had no answer. Apparently Hitler had originally intended to stage a great spectacle modeled on the Soviet show trials of the 1930s, with radio and film coverage and lengthy press reports, but he was soon forced to abandon all such plans. Schulenburg, for example, declared before the court: “We resolved to take this deed upon ourselves in order to save Germany from indescribable misery. I realize that I shall be hanged for my part in it, but I do not regret what I did and only hope that someone else will succeed in luckier circumstances.” Similar declarations from numerous defendants increasingly put the authorities on the defensive, and on August 17, 1944, Hitler forbade any further reporting of the trials. In the end, not even the executions were publicly announced. 7

The Gestapo had considerable difficulty determining the breadth of the conspiracy. It is known, for instance, that Stieff and Fellgiebel held out for at least six days under torture without revealing anything. Contrary to legend, no list of conspirators or a projected cabinet was ever found, and as late as August 8 Yorck was able to tell prison chaplain Harald Poelchau that the Gestapo still knew nothing about the Kreisau Circle. Moltke’s name was not uttered until Leber’s interrogation on August 10. 8Schlabrendorff, who survived the war to write a detailed account of the four types of torture employed-beginning with a device to screw spikes into the fingertips and progressing to spike-lined “Spanish boots,” the rack, and other horrors-did not reveal the names of his co-conspirators at Army Group Center, even when the mutilated corpse of his friend Tresckow was exhumed and shown to him. Despite severe torments, not much more than was already known could be dragged out of Jessen, Langbehn, Oster, Kleist-Schmenzin, and Leuschner. But what these men refused to reveal in so-called intensified interrogation-in which all the horror and vengeful fury were brought to bear on them-the Allies now did. As if eager to do one last favor for Hitler, British radio began regularly broadcasting the names of people alleged to have had a hand in the coup. Roland Freisler, the president of the People’s Court, was even able to show Schwerin von Schwanenfeld an Allied leaflet that heaped scorn on the conspirators, just as the Nazis’ propaganda was doing.”

The military “court of honor” that Hitler had demanded met on August 4, with Field Marshal Rundstedt presiding and Field Marshal Keitel, General Guderian, and Lieutenant Generals Schroth, Specht, Kriebel, Burgdorf, and Maisel serving as associates. Without any hearings or presentation of evidence, they drummed twenty-two officers out of the Wehrmacht, thus depriving them of the legal protections of a court-martial, just as Hitler wanted. However extreme this step may have appeared to be, it was actually only the final act in a lengthy process that had revealed to all that the unity and cohesiveness of the army had long since been shattered. It was the last of many gestures of submission to Hitler’s will.

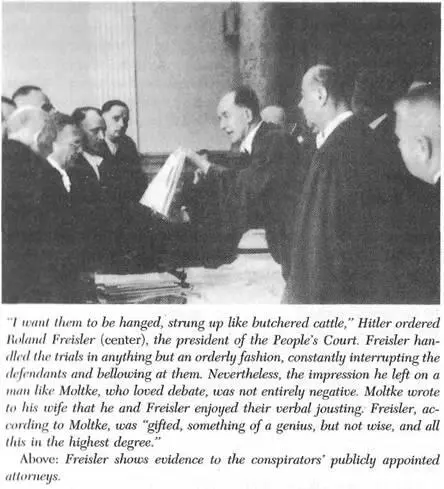

Responsibility for trying the accused officers and the other participants in the attempted coup fell now to the People’s Court, which had been specially constituted in 1934 to judge “political crimes.” Hitler ordered the cases to be heard in closed chambers before a small, select audience. He invited Freisler and-if the reports are accurate-even the executioner to Führer headquarters, where he instructed them to refuse the condemned men all religious and spiritual comfort. “I want them to be hanged, strung up like butchered cattle,” Hitler said. 10

The trials began on August 7 in the great hall of the Berlin People’s Court, which was hung with Nazi flags for the occasion. The accused were Witzleben, Hoepner, Stieff, Hase, Bernardis, Klausing, Yorck, and Hagen. To further humiliate the conspirators, they were forbidden to wear neckties, and Witzleben was even denied suspenders for his trousers. Hoepner was dressed in a cardigan. All bore the signs, as one witness reported, of the “tortures they had suffered while in custody.” 11Presiding over the scene was Roland Freisler, attired in his red judicial robes and seated beneath a bust of the Führer.

Freisler had been appointed president of the People’s Court two years earlier, and in him the regime found a man very much in its own image. Hitler always felt a certain distrust toward Freisler, however, and his likening of him to Andrei Vishinsky, the chief prosecutor In the Moscow show trials, suggests the reason: Freisler had been taken prisoner by the Russians during the First World War and had become a Soviet commissar after the October Revolution; he liked to boast that he had begun his career as a diehard Communist. With his cynical bent and taste for radical politics, he joined the Nazis in 1925, throwing himself into political and journalistic tasks on behalf of the party and reaping his reward with an appointment as state secretary in the Ministry of Justice. Seizing on a comment by Hitler in his address to the Reichstag justifying the Night of the Long Knives, he made himself a vocal advocate of Gesinnungsstrafrecht, harsh laws that called for defendants in political cases to be punished not so much for their deeds as for the convictions underlying those deeds.

Читать дальше

![Traudl Junge - Hitler's Last Secretary - A Firsthand Account of Life with Hitler [aka Until the Final Hour]](/books/416681/traudl-junge-hitler-s-last-secretary-a-firsthand-thumb.webp)