These and other tips made Stauffenberg feel even more strongly that he had to act immediately. He felt driven as well-perhaps even more-by his chagrin at the delays and at the lack of resolve over the previous weeks. His exhaustion and his raw nerves, mentioned in various accounts, undoubtedly added to his sense of urgency. One observer spoke, with poetic overtones, of the “dark shadow” that seemed to have enveloped him since June. In any case, as Stauffenberg now said to Kranzfelder, “There’s no choice now; we’ve crossed the Rubicon.” 20

The next day, July 19, was spent on preparations. By about noon Olbricht’s and Stauffenberg’s staffs were busy alerting Witzleben, Hoepner, Berlin city commandant Paul von Hase, Colonel Jäger, Major Ludwig von Leonrod, and the large number of other officers who had roles to play. In the early evening Stauffenberg called on Quartermaster General Wagner in Zossen, hoping perhaps to straighten out the difference of opinion that had arisen on July 15. At the end of their discussion Wagner arranged for a special airplane to be placed at Stauffenberg’s disposal for the return flight from Rastenburg. After Stauffenberg had taken his leave Wagner informed Stieff of the preparations.

Early on the morning of July 20 Wagner greeted Lieutenant Colonel Bernhard Klamroth by asking, “What are we going to do if the assassination really is today?” 21Rarely had the conspirators’ lack of confidence been so clearly expressed as in this naive-sounding question; it was almost as if an actual assassination was the last thing they expected. Perhaps the sense, reinforced over the years, that whatever they touched would inevitably turn to dust lent all their plans a noncommittal air, which could not help but affect their determination to act. Just a few hours later this ingrained skepticism would have fatal consequences.

First, however, the notion that nothing ever happened as a result of their efforts was about to be shattered. Wagner’s query suggests he suddenly realized that Stauffenberg had brought to the resistance an unwavering determination to carry out the plot. One might wonder, as the historian Peter Hoffmann has, why Stieff, Wagner, Meichssner, Fellgiebel, and other officers who had access to Hitler palmed the assassination attempt off on Stauffenberg, whose physical dexterity was limited and whose absence from Berlin would seriously jeopardize the coup following the assassination. In all likelihood, they hadn’t fully understood that they were now irrevocably implicated, and that if Stauffenberg failed their own ruin was assured as well.

All the conspirators wrestled with their doubts that the coup would be successful. Hofacker said he felt that the chances were very small, as did Schulenburg and Berthold von Stauffenberg. Tresckow stated that the attempt would “very likely go awry,” and Beck expressed similar sentiments. Even Stauffenberg was apparently skeptical and told a young officer in early July that “it was questionable whether it would succeed.” In his next breath he revealed how far he had moved from hopes of achieving any far-reaching aims, a feeling shared and in many cases expressed by his close friends. “But even worse than failure,” Stauffenberg continued, “is to yield to shame and coercion without a struggle.” 22This was Stauffenberg’s only certainty. Everything else that followed would be a “leap in the dark.” 23

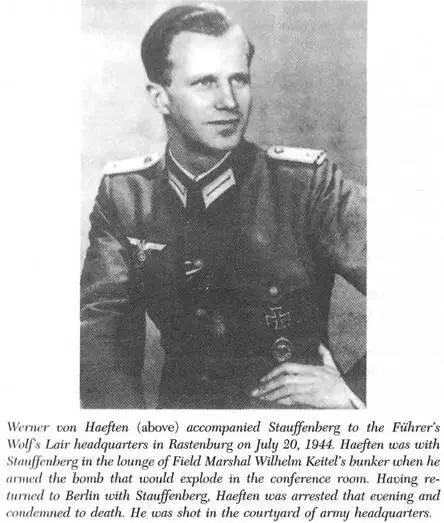

Stauffenberg flew into the Rastenburg airfield shortly after 10:00 a.m. with Werner von Haeften and Helmuth Stieff, who had boarded the flight in Zossen. He immediately headed for the officers’ mess in Restricted Area II, carrying in his briefcase only the papers he needed for the reports he was expected to give. Haeften, meanwhile, carried the two bombs in his briefcase and accompanied Stieff to OKH headquarters. The plans called for Haeften and Stauffenberg to meet shortly before the briefing in the Wolf’s Lair to exchange briefcases.

At around eleven o’clock Stauffenberg was summoned by the chief of army staff, General Walther Buhle, and after a short meeting they proceeded together to a conference with General Keitel in the OKW bunker in Restricted Area I. Here Stauffenberg learned that on account of a visit by Mussolini what was to have been a noon briefing with Hitler had been put back half an hour to twelve-thirty. Immediately following the conference with Keitel, Stauffenberg asked the general’s aide, Major Ernst John von Freyend, to show him to a room where he could wash up and change his shirt-July 20 was a hot day.

As Keitel and the other officers headed toward the briefing barracks, Stauffenberg met Haeften in the corridor. Together they withdrew into the lounge in Keitel’s bunker, where Stauffenberg set about installing and arming a fuse in the first bomb. He had barely begun, however, when a most unfortunately timed telephone call came from General Fellgiebel, who asked to speak with Stauffenberg on urgent business. Freyend sent Platoon Sergeant Werner Vogel back to the bunker to urge Stauffenberg to hurry.

As Vogel entered the lounge, he saw the two officers stowing something into one of the briefcases. He informed them of the call, adding that the others were waiting for them outside. Meanwhile Freyend shouted from the entrance, “Stauffenberg, please come along!” With Vogel standing in the doorway, Stauffenberg closed the briefcase as swiftly as possible while Haeften swept up the papers that were lying around and stuffed them into the other briefcase.

Fellgiebel’s telephone call and the intrusion of Sergeant Vogel may well have determined the course of history, for it is likely that they prevented Stauffenberg from arming the fuse on the second package of explosives. No one knows for certain why Stauffenberg did not place the second bomb in his briefcase alongside the one whose timer had already been activated, since the explosion of one would surely have set off the other as well. Some have claimed that both charges would have been too bulky and heavy to carry into the briefing room unobtrusively. This argument is hardly convincing, however, as the bombs weighed only about two pounds each, and Haeften had carried them both around in his briefcase earlier without any problems.

Stauffenberg was certainly nervous, and Vogel’s sudden appearance in the room must have given him a fright, but the most probable explanation for his bringing only the one bomb is that he was not fully aware of how such explosives work. Believing that a single bomb would suffice, he probably did not adequately consider the cumulative effect of two bombs. It may be that the second charge was only taken along as an alternative in the event that something went wrong, especially since the two timers were set differently, one for ten minutes and the other for thirty. What is clear, according to all experts, is that inclusion of the second charge, even without a detonator, would have magnified the power of the blast not twofold but many times, killing everyone in the room outright. 1

Together with General Buhle and Major Freyend, Stauffenberg hurried out of the OKW bunker, briefcase in hand. They crossed the three hundred and fifty yards to the wooden briefing barracks, which lay behind a high wire fence in the innermost security zone, the so-called Führer Restricted Area. After declining for the second time Freyend’s offer to carry his briefcase, Stauffenberg finally turned it over to him at the entrance to the barracks, asking at the same time to be “seated as close as possible to the Führer” so that he could “catch everything” in preparation for his report.

Читать дальше

![Traudl Junge - Hitler's Last Secretary - A Firsthand Account of Life with Hitler [aka Until the Final Hour]](/books/416681/traudl-junge-hitler-s-last-secretary-a-firsthand-thumb.webp)