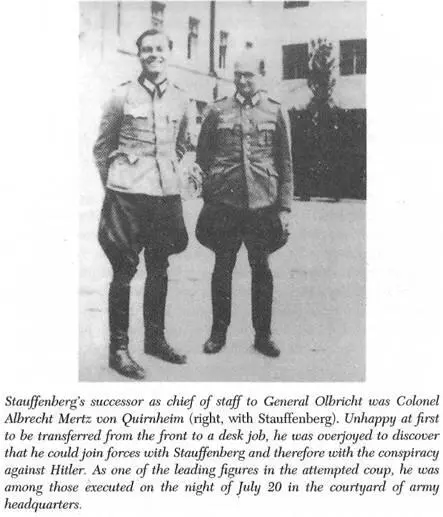

The real reasons the attack of July 15 was called off can no longer be determined with any certainty. Whatever they were, though, this failure highlighted the resistance’s most serious deficiency. There is no doubting the moral integrity of the conspirators, their hatred of the Nazi regime, and their horror at the atrocities committed in Germany’s name. But the distance between outrage and action is great. In his telephone call to Berlin, where Witzleben, Hoepner, Olbricht, Mertz von Quirnheim, Hansen, Haeften, and many others were gathered, Stauffenberg, faced with the opposition of Stieff, Wagner, and Fellgiebel to an attack that would not also kill Himmler, apparently intended to ensure that his fellow conspirators were still with him and to win a consensus for proceeding despite Himmler’s absence. Alter a half hour of dithering, which wasted precious time and demonstrated to the impatient Stauffenberg how much his fellow conspirators relished endless discussion and debate, the answer came back that the majority of those assembled wanted to postpone the attempt. None of them, apart from Mertz von Quirnheim, seems to have appreciated the traumatic effect their response had on Stauffenberg. That evening Mertz spoke to his wife about the “deeply depressing feeling… of finding yourself all alone at a moment when great courage and determination are required to succeed.” Of the abortive efforts to bring the bomb to Hitler one conspirator noted that for the third time in just a few days “Stauffenberg has gone down that terrible road in vain.” 14

According to one account, the news that the attack had been postponed once again eased the tension at army headquarters on Bendlerstrasse and gave rise “to an almost euphoric mood.” This report may not be reliable, however, particularly with regard to General Olbricht. He knew only too well what consequences might attend his unauthorized issuance of the Valkyrie orders in Fromm’s absence. 15Olbricht departed at once to cancel the untimely alert. He drove to the affected units in Potsdam and Glienicke, and, concealing his involvement, expressed his “particular appreciation” to General Otto Hitzfeld, the commander of the Döberitz infantry school, who was partially initiated into the conspiracy. He also made note of the fact that the new commander of the Krampnitz panzer school, Colonel Wolfgang Glaesemer, probably could not be won over to the cause, and rescinded the alert.

The next evening Stauffenberg met for the last time with his closest friends. Gathered together at the house on Tristanstrasse in the Wannsee district of Berlin where he lived with his brother Berthold were Ulrich Schwerin von Schwanenfeld, Peter Yorck von Wartenburg, Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg, Adam von Trott zu Solz, Cäsar von Hofacker, Albrecht Mertz von Quirnheim, and Georg Hansen. Once again they discussed ways of proceeding: the “western solution,” outlined above, and the “Berlin solution,” according to which the central signals system would be seized for twenty-four hours and Hitler’s headquarters outmaneuvered by a number of irreversible withdrawals of German forces. Both these ideas were rejected, as was the idea discussed occasionally of ending the war by means of a direct agreement between the commanders in chief of the various national armies, speaking as “one soldier to another” and circumventing governments entirely.

All these solutions ran aground on the hard fact that no progress could be made in any of these directions-either with the Allies or with the German commanders-so long as Hitler was alive. The Allies had absolutely no intention of negotiating with him and the commanders little stomach for openly opposing him. The only option left, the conspirators on Tristanstrasse concluded, was indeed assassination. There is some indication that Stauffenberg was eager to hold this lengthy discussion, which stretched well into the night, in order to allay once and for all both his own qualms about doing “the dirty deed” and those of so many others. It was now clearly too late for the conspirators to turn the assassination of Hitler to advantage and negotiate better political terms with the Allies. All that remained was the possibility of reducing the number of war victims and sparing Germany some measure of humiliation by purging itself of the Nazis. In a subsequent conversation with Beck, Stauffenberg reviewed what had gone wrong on July 15 and pledged that “the next time he would act, come what may.

* * *

As always happened when things were heading toward a climax, more bad news arrived-of precisely the kind that had repeatedly sapped the conspirators’ resolve in the past. First, while returning from the front Field Marshal Rommel was severely injured when his car was strafed by an airplane. To be sure, he had never really figured in the plans for a coup, but when he had been asked the previous day how he would react if Hitler rejected his “ultimatum,” he had coolly replied that he would “throw open the western front,” thereby fueling the opposition’s lingering hope of unilaterally putting a stop to the fighting on that front. 17Furthermore, Rommel was extremely popular with the general public, and though he was certainly not an enemy of the regime, the insurgents hoped that he might join them if the circumstances were right. Rommel’s participation would have helped prevent the creation of another stab-in-the-back legend, a concern that had so preoccupied the conspirators.

In the midst of all the other bad news, however, the loss of Rommel was scarcely noticed. Much more disturbing to the conspirators was a tip from Arthur Nebe that Goerdeler had been named by Wilhelm Staehle and was about to be arrested. Stauffenberg responded to the information by asking Goerdeler “to disappear as quickly as possible and not endanger the entire conspiracy by running around Berlin making telephone calls.” Goerdeler, already bitter at having been pushed about for months and feeling increasingly squeezed to the periphery of the conspiracy, took this as another attempt to belittle him, especially since Stauffenberg did not mention that he had been summoned to report to Hitler’s headquarters on July 20, just two days hence. Nevertheless, Stauffenberg did ask Goerdeler to remain ready for a coup, and Goerdeler let it be known that his hiding place over the next few days would the estate of his friend Baron Kraft von Palombini in Rahnisdorf. 18

Possibly even more disconcerting was a warning delivered to Stauffenberg on July 18 by Lieutenant Commander Alfred Kranzfelder: a rumor was circulating in Berlin, Kranzfelder reported, that “Führer headquarters would be blown sky-high that very week.” It seems that a young Hungarian nobleman had picked up this piece of information at the Potsdam home of the widow of General von Bredow, one of those murdered in the Rohm putsch. Later it turned out that the source was none other than one of the Bredow daughters, who was on friendly terms with Werner von Haeften, and it was reasonable to conclude that the information had thus far been confined to the Bredow household and had not actually spread to Berlin. But Schulenburg also informed the conspirators that day that “two men had been inquiring about him in his neighborhood” and that he did not think they were harmless visitors. 19

Читать дальше

![Traudl Junge - Hitler's Last Secretary - A Firsthand Account of Life with Hitler [aka Until the Final Hour]](/books/416681/traudl-junge-hitler-s-last-secretary-a-firsthand-thumb.webp)