Stauffenberg’s patience was wearing thin. Just before the conference was to begin, he asked Stieff, “My God, shouldn’t we do it?” But Stieff pointed out Himmler’s absence, thereby imposing, perhaps unwittingly, another difficult condition on an assassination attempt that he himself was still not prepared to carry out. In the end Stauffenberg abandoned his plan and decided not to detonate the bomb he had taken along. When the news reached Berlin, Goerdeler commented, “half laughing and half crying, ‘They’ll never do it!’ ” 10

Three days later, Stauffenberg was ordered to report for another meeting, on July 15, this time at the Wolf’s Lair, where Hitler had returned even though-or perhaps because-Russian forces were now only about sixty miles from the East Prussian border. Stauffenberg used the intervening time to review some of the technical and personnel details that would be crucial to the success of the coup. An agreement had been reached with General Erich Fellgiebel, the chief army signal officer, to interrupt signal traffic to and from Hitler’s headquarters at a given moment. But Fellgiebel had pointed out on several occasions that little could be done in advance because although there was a central communications center, the army, the air force, the SS, and the Foreign Office each had their own signal lines. In addition, care would have to be taken not to cut off signals to and from the troops at the front. Thus, Fellgiebel maintained, Führer headquarters could only be isolated for a limited period; everything depended, he said, on doing exactly the right thing at exactly the right time. Meanwhile, however, improvements were to be made in communications with the liaison officers in the military districts, whose cooperation would be so essential to Operation Valkyrie; the preparedness of the army units in the Berlin area to take fast action had to be ensured; and numerous other aspects of mobilization, which were largely in Olbricht’s hands, needed to be clarified. The final problem facing Stauffenberg was how to handle the pliers for igniting the bomb, which had to be specially constructed for him because of his mutilated hand.

The statements to be made to the public were also checked again. A number of versions are still extant, all of them rough drafts or working copies that contain repetitions and contradictions. Apparently the conspirators never managed to produce a text acceptable to everyone. One proclamation came from Goerdeler, who evidently drafted it in concert with Tresckow and the lawyer Josef Wirmer. Leber and Reichwein produced another, and Beck a third, which was specifically addressed to the troops. Stauffenberg also drafted a proclamation, which was discussed and amended on a number of occasions within his circle of friends. The original text did not survive the war, but his close friend Rudolf Fahrner wrote a short summary from memory in August 1945.

According to Fahrner, Stauffenberg’s statement began by informing the German people “without further explanation that…Adolf Hitler was dead. Then came a few sentences condemning the party leaders,” whose behavior had created “the need and duty to intervene.” The head of the transitional government (whose name Fahrner never learned) provided “assurances that he and those who had placed themselves at his disposal wanted nothing for themselves. The nation would be summoned as soon as possible to freely determine the future constitution of the state, which would be new and innovative. The head of the transitional government,” Fahrner wrote, “swore on behalf of himself and his colleagues to act in strict and complete accordance with the law and neither to do nor to tolerate anything that contravened divine or human justice. In return he demanded unconditional obedience for the duration of his government. It was then proclaimed that crimes and unlawful acts committed under party rule would have to be thoroughly atoned for, but no one would be persecuted for his political convictions. This was followed by an announcement that the transitional government would do everything in its power to reach a truce with the enemy as soon as possible” and that this could not be achieved “without great loss and sacrifice.” 11

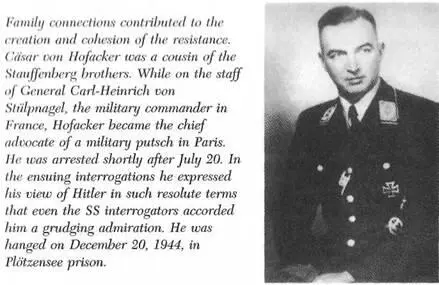

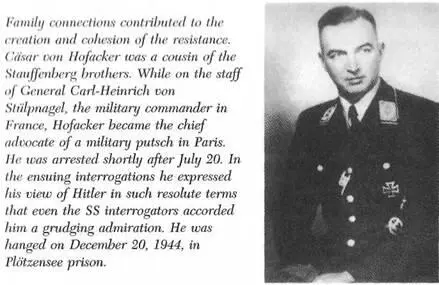

On the evening of his return from the July 11 meeting at Berchtesgaden, Stauffenberg had met with his cousin Cäsar von Hofacker, who was on Stülpnagel’s staff in Paris, to orchestrate plans for the coup. Hofacker informed him that Field Marshals Hans von Kluge, who had recently been named commander in chief in the West, and Erwin Rommel, the chief of Army Group B, had both said that Allied superiority, especially in the air, was so great that the front could be held for only two or three more weeks at best. The troops were “withering” under the incessant onslaught. Stülpnagel was most willing to assume an active part in the coup, while Kluge remained as coy as ever and Rommel basically kept his distance. Rommel had endured a tense confrontation with Hitler one month earlier at the Wolf Gorge II headquarters near Margival, north of Soissons, incurring Hitler’s wrath by calling attention to the Allies’ vast material advantage and advising that the war be ended. But Rommel was not prepared to resort to violence. A few days later he drafted an “ultimatum” telegram to the Führer, in which he begged him to draw “the political consequences” of the imminent collapse of the western front; but he was still unwilling to go any further. It remains an open question whether Rommel would ever have joined the opposition. The growing chasm between him and the conspirators in Berlin is apparent in the fact that he allowed his chief of general staff, Hans Speidel, to persuade him to remove the word political from his telegram before sending it, so as not to “annoy” the Fuhrer unnecessarily. 12

When Stauffenberg flew to Rastenburg in the early morning of July 15, along with Fromm and Captain Friedrich Karl Klausing, the coup was more thoroughly planned and the circle of supporters wider than four days earlier. Stauffenberg and Olbricht’s determination to take the plunge that day is clearly evident in Olbricht’s decision to issue the Valkyrie alert to the guard battalion and the army schools around Berlin at around eleven o’clock, or two hours before the earliest possible assassination attempt. In so doing, he risked squandering the only opportunity he would have to act on his own authority. Moreover, Stauffenberg had apparently abandoned his insistence that the attack be carried out only if Himmler was present.

Immediately on arriving at Rastenburg, however, Stauffenberg encountered Fellgiebel and Stieff, both of whom were adamant that the attack be canceled because of Himmler’s absence. They also told Stauffenberg that Quartermaster General Eduard Wagner had been most definite the previous evening that the assassination ought only to be carried out “if the Reichsführer-SS is present.” Both Olbricht’s decision to issue the Valkyrie alert and Stauffenberg’s evident exasperation with his own hesitation on July 11 seem to indicate, though, that this time Stauffenberg was determined to overcome any such objections.

But “it all came to nothing again today,” Stauffenberg was forced to admit to Klausing after the briefing as they headed for dinner in Keitel’s special train. According to one version of events, Stieff prevented the attack by removing the briefcase with the bomb while Stauffenberg was out of the conference room making a telephone call to army headquarters in Berlin. According to another version, Stauffenberg himself wavered, worrying that Stieff, Wagner, and Fellgiebel’s vehement insistence that the attack not be carried out amounted to an abrogation of their agreement to participate. All that Stauffenberg ever said on the subject was that, to his surprise, “a meeting was called at which he himself had to give a report, and thus he never had an opportunity to carry out the assassination,” his brother Berthold recalled. 13

Читать дальше

![Traudl Junge - Hitler's Last Secretary - A Firsthand Account of Life with Hitler [aka Until the Final Hour]](/books/416681/traudl-junge-hitler-s-last-secretary-a-firsthand-thumb.webp)