Brauchitsch summoned the generals to a meeting on Bendlerstrasse on August 4. It soon became apparent that all the commanding generals believed that a spreading war would prove catastrophic for Germany. Busch and Reichenau, however, did not think that an attack on Czechoslovakia would necessarily lead to war with the Western powers, and as a result the tormented Brauchitsch did not even mention Beck’s proposal that the generals attempt to pressure Hitler by threatening mass resignation. At the end of the meeting Brauchitsch did, however, reconfirm their unanimous opposition to a war and their conviction that a world war would mean the destruction of German culture. 14Shortly afterwards, Hitler was informed about the meeting by Reichenau and he immediately demanded Beck’s dismissal as chief of general staff. To show his displeasure he invited neither Beck nor Brauchitsch to a conference at his compound on the Obersalzberg on August 10; there he informed the chiefs of general staff of the armies and the air force that he had decided to invade Czechoslovakia.

Eight days later Beck submitted his resignation. This step and the way in which it was taken revealed once again the submissiveness and political ineptitude of the officer corps. After the Fritsch affair Beck had declared that he must remain at his post in order both to work for the rehabilitation of his humiliated superior and to prevent the reduction of the army to a mere tool of the Führer. His ensuing dispute with Hitler, however, which took the form of a series of memoranda opposing the Führer’s plans for war and for the reorganization of the high command, proved to be the “final battle” of the officer corps in its struggle to maintain a say in decisions of war and peace. 15Now Beck cleared himself out of Hitler’s way, as it were, becoming merely an outraged, and later despairing, observer without position or influence.

Only a few days earlier Erich von Manstein, his chief of operations, had written him a letter urging that he remain at his post because no one had the “skill and strength of character” to replace him. Beck’s authority was indeed widely acknowledged throughout the officer corps. He was a clear, imaginative, rigorous thinker of great integrity. Even Hitler could not shake the aura of easy superiority Beck projected in every word and deed. During the Fritsch crisis the Führer had confided in a member of his cabinet that Beck was the only officer he feared: “That man could really do something.” 16Later Beck effortlessly assumed a leadership role in the opposition. No one doubted that if a successful putsch was launched he would become chief of state. “Beck was king,” a contemporary recalled. 17If there was a flaw in his cool, pure intelligence, it lay in his lack of toughness and drive. He was “very scholarly by nature,” one of his admirers commented. Other opposition figures also found that he provided more analytical acuity than leadership at crucial moments. 18

Beck was also probably less of a political strategist than the situation required and was certainly not conversant with the kinds of maneuvers and ploys at which Hitler was so adept. That is why he readily acquiesced to Hitler’s request that his resignation not be made public lest it provoke an unfavorable reaction. As a result, the decision he had made after so much painful reflection had no public impact. Beck later admitted that he had made a mistake, adding a revealing justification that illustrates the helplessness of his position: it was not his way, he said, to be a “self-promoter.” 19Hitler did not even bother to grant him an audience when he took his leave.

Nonetheless, upon his departure Beck commended his successor, Franz Halder, to all those with whom he was on confidential terms. Indeed, only a few days after assuming his new post, Halder summoned Hans Oster to an interview. After a few exchanges of views about Hitler’s foreign designs, Halder asked his guest point-blank how the preparations for a coup were progressing. More clearly than Beck, Halder recognized that the ingloriously abandoned plan for a “generals’ strike” would only make sense as the first step in a coup; otherwise it was better left undone. Hitler could easily have found replacements for all the seditious generals and knew far too much about power and how to keep it simply to back down in the face of such opposition. The historian Peter Hoffmann quite rightly points in this regard to Manstein’s comment at the Nuremberg trials that dictators do not allow themselves to be driven into things, because then they would no longer be dictators. 20

Halder was a typical general staff officer of the old school: correct, focused, and outspoken. Observers also noted a certain impulsiveness, which, for the sake of his career, he had learned to control, if not overcome. Not long after his meeting with Oster he spoke with Gisevius for the first time, soon turning to concrete questions about plans for the coup and describing Hitler as “mentally ill” and “bloodthirsty.” 21Here and elsewhere, he proved that he was a man far more capable of action than Beck, who immersed himself in philosophical contemplation. Halder had resolved the conflict between the loyalty traditionally expected of a soldier and the need to topple Hitler and no longer felt inhibited from taking action by his oath to the Führer. As early as the fall maneuvers of 1937, he had encouraged Fritsch to use force against Hitler, and after Fritsch’s treacherous removal he had pressed for “practical opposition.” More clear-sighted than most of his fellow conservatives and less compromising in his values, he realized that Hitler was a radical revolutionary prepared to destroy virtually everything. Despite the adoring crowds at Hitler’s feel, Halder considered his rule highly illegitimate because it stood outside all tradition: truth, morality, patriotism, even human beings themselves were only instruments for the accrual of more power. Hitler, in Halder’s view, was “the very incarnation of evil.” By nature a practical, realistic man, meticulous to the point of pedantry, Halder was not, however, cut out for the role of conspirator and the very perversity of the times can be seen in the fact that such a man felt driven to such un undertaking. He later said he found “the need to resist a frightful, agonizing experience.” 22Halder refused to be a party to any sort of ill considered action and insisted that a coup would only be justifiable as a last resort.

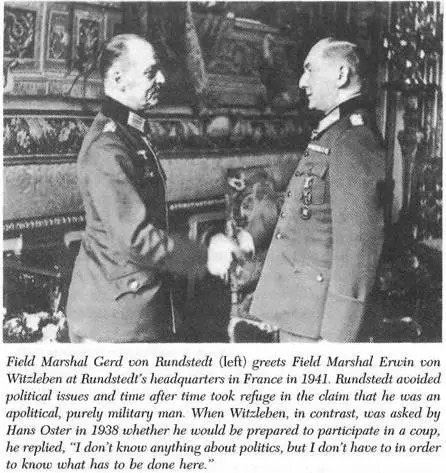

Upon assuming his new post on September 1, Halder informed Brauchitsch that, like his predecessors, he opposed the Führer’s plans for war and was determined to “exploit every opportunity that this position affords to carry on the struggle against Hitler.” If this comment illustrates Halder’s own character, the reaction of the overly pliable commander in chief, who felt himself forced from one horror to the next, was perhaps even more revealing: as if in gratitude, Brauchitsch spontaneously seized both Halder’s hands and shook them. 23A series of discussions soon ensued that included Witzleben; Hjalmar Schacht; Beck; the quartermaster general of the army, Colonel Eduard Wagner; and, most important, Hans Oster, the indefatigable driving force and go-between of the opposition. The necessary preconditions for a coup were spelled out and the aims more precisely defined.

In the course of these discussions a perhaps unavoidable rift emerged between the methodical, deliberate chief of general staff and Oster’s immediate associates. Halder was primarily concerned with finding ways to justify a coup morally and politically, not only for himself but also for the army and the general public. A coup would only be warranted, in his view, if Hitler ignored all warnings and issued final instructions to launch a war. At that point, but not before, Halder said, he would be prepared to give the signal for a putsch. Oster and the impetuous Gisevius, on the other hand, were far more radical in their thinking and no longer had any patience for tactical considerations. In their view the regime had to be struck down by any means possible. Hitler’s warmongering may have provided an inducement and opportunity, but it was not the primary reason for taking action. Although this basic difference of opinion surfaced now and then, it was never really resolved, leading one of the more resolute opponents of the Nazi regime to speak, with some justification, of a “conspiracy within the conspiracy.” 24

Читать дальше

![Traudl Junge - Hitler's Last Secretary - A Firsthand Account of Life with Hitler [aka Until the Final Hour]](/books/416681/traudl-junge-hitler-s-last-secretary-a-firsthand-thumb.webp)