It is hardly surprising, therefore, that Oster’s next emissary, the industrialist Hans Böhm-Tettelbach, also returned empty-handed. Far from allowing himself to become downhearted, Oster hoped to make his messengers seem more reliable by seeking assistance from co-conspirators in the Foreign Office. He asked Erich Kordt, the chief of the Ministers’ Bureau, to draft a message to the British government requesting a “firm declaration” of opposition to Hitler’s warmongering, a statement whose meaning would be “apparent even to ordinary people.” If such a document could be obtained, Oster added, there would “be no more Hitler.” 3It was too risky to carry a copy of the message, so one of Kordt’s cousins was asked to memorize it and repeat it for his brother Theo Kordt, who worked in the German embassy in London.

Although Theo Kordt aroused greater interest than his predecessors had and was even admitted to 10 Downing Street through a back entrance for an interview with Lord Halifax, the foreign minister, his mission, too, proved futile. Halifax listened attentively, to be sure, and seemed impressed when Kordt reminded him that Great Britain might have averted war in 1914 by issuing a similar declaration. He assured his guest as they parted that he would inform the prime minister and certain cabinet members about the gist of their conversation, so that Kordt departed with his hopes high. Once again, however, Great Britain could not be persuaded to issue a public declaration. The only noticeable effect of the conversation came in a letter Chamberlain sent to Hitler just before the outbreak of war in late August 1939, in which he mentioned the parallel to 1914 and expressed his hope that this time “no such tragic misunderstanding” would arise. A few weeks later, when the die had already been cast, Halifax commented to Theo Kordt, with a note of regret, “We could not be as candid with you as you were with us,” for at the time of their conversation Whitehall had already decided to yield to Hitler’s demands. 4

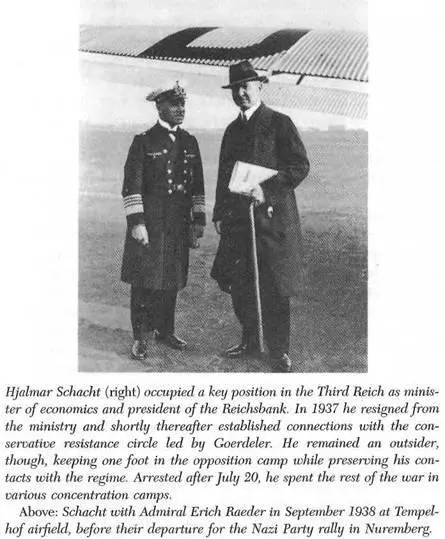

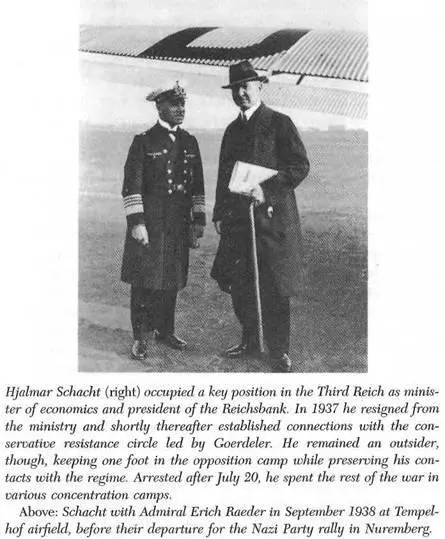

So it went, over and over again. By the time Erich Kordt was drafting his message, the secretary of state in the Foreign Office, Ernst von Weizsäcker, had already begged the high commissioner for Danzig, Carl Jacob Burckhardt, “with the frankness of a desperate man betting everything on one last card,” as Burckhardt later described it, to use his connections to persuade the British government to make some definitive gesture, perhaps by “sending out a general with a riding crop,” whose language Hitler would presumably understand. 5But all efforts were in vain. In the summer of 1939, just before the invasion of Poland, when war again seemed imminent, Hjalmar Schacht met several times with Montagu Norman, the governor of the Bank of England. Fabian von Schlabrendorff, Helmuth von Moltke, Erich Kordt, Adam von Trott, and Ulrich Schwerin von Schwanenfeld all joined the procession. But the British remained impassive, stoic, and distrustful, offering little more than empty words.

British policy at this time has often been criticized as inadequate. The pitiful failure of the German opposition figures’ forays was due in large measure to Chamberlain’s appeasement policy, upon which all attempts ultimately floundered. Britain had emerged exhausted from the First World War, and the prime minister wished to spare his nation another passage at arms, which would overtax its remaining strength and, it seemed, inevitably bring about an end to the empire. Chamberlain was no sentimental pacifist; there was more cool realism and even hard-hearted calculation in him than was later generally realized. He believed that a policy of prudent step-by-step appeasement would have a literally disarming effect, even on a man such as Hitler, and he pursued this course with conviction and tenacity. It was the only way, Chamberlain felt, to secure the peace-a goal for which he was prepared to pay virtually any price that did not compromise British honor and patience.

This is the background against which all the forays made by Hitler’s opponents must be seen. The tactics the opposition had adopted were the very opposite of the British cabinet’s, for they sought confrontation where Chamberlain hoped to avoid it. All they wanted from the British were words and gestures which they erroneously believed that Whitehall could easily deliver, because they were convinced that the Western powers would never abandon Czechoslovakia. In fact, Chamberlain was secretly prepared to do just that. To satisfy the requests of the German conspirators, the British would therefore have had to reverse their entire policy of conciliation. Furthermore, the British feared that the statements requested of them might goad the irascible Hitler to make decisions that would inevitably lead to war. Eventually, in view of Berlin’s constant exacerbation of the tensions, Lord Halifax did send a message to the German government on September 9, 1938, reflecting at least somewhat the posture urged on Whitehall by the conspirators. The British ambassador to Berlin, Sir Nevile Henderson, flatly refused, however, to deliver a message so clearly out of step with the official conciliatory approach. Similarly, when Vansittart had written a memorandum a few months earlier advising a firmer posture toward Hitler, it was suppressed from within the bureaucracy. Vansittart’s arguments were based on information channeled to him from German opposition circles detailing the Reich’s economic, psychological, and military un-preparedness for war. 6

As carefully calculated as Chamberlain’s policies were, there was one element in the equation that he failed utterly to comprehend because it lay so far outside the orbit of his experience. For the sake of peace he was prepared to see Germany annex the Sudetenland, then Bohemia, and then even the Polish Corridor and parts of Upper Silesia; the new government in Berlin, he firmly believed, would eventually become as “sated, indolent and quiescent” as even the most rapacious of beasts. 7

But Chamberlain did not understand Hitler at all, and his incomprehension would prove the undoing of his shrewdly devised policy. As a European statesman of the old school, the prime minister thought in terms of national interest. He had some grasp of such imponderables as injured pride and honor and the redress that Hitler constantly demanded. What he failed to realize, however, was that Hitler was not really serious about such things, indeed that amid his extravagant racist fantasies of saving the world there was little room for such categories as “nation,” “interests,” or even “pride.” Like the Germans themselves-and probably like everyone else-the prime minister failed to fathom the radical otherness that Hitler introduced into European politics. In the words of a deeply shocked German conservative during the early years of Hitler’s chancellorship, the Führer did not really seem to belong in this world. He “had something alien about him, as if he sprang from an otherwise extinct primeval tribe.” 8

One cannot judge the efforts of the German conspirators at this time without considering several other factors as well, especially the confusion they spread when abroad, despite their agreement about the ultimate purpose of their trips. It was, of course, very difficult under the circumstances to meet and adequately discuss strategy among themselves. Böhm-Tettelbach, for instance, did not even know when he traveled to London that Ewald von Kleist had been there just two weeks earlier on the same mission. Even more disturbing were the contradictions in what the various emissaries had to say. For instance, Goerdeler demanded-like Hitler himself-not only the cession of the Sudetenland but also, as if anticipating the Führer, the elimination of the Polish Corridor and the return of Germany’s former colonies. Meanwhile Kleist spent his time advocating the restoration of the monarchy. When Adam von Trott declared that a new German government would preserve Hitler’s territorial gains, he was unceremoniously evicted from the home of an English friend.

Читать дальше

![Traudl Junge - Hitler's Last Secretary - A Firsthand Account of Life with Hitler [aka Until the Final Hour]](/books/416681/traudl-junge-hitler-s-last-secretary-a-firsthand-thumb.webp)