There is much to indicate that Hitler was already leaning in this direction. And at this point, another explosive police record turned up thanks to the assiduous efforts of Himmler and Heydrich, who produced it, and Göring, who turned it over to the Führer. This one enabled Hitler to rid himself of the entire high command of the Wehrmacht, as the Reichswehr was now called, reducing the army to the purely instrumental role he required for his war policy. The record in question accused the commander in chief of the army of homosexuality. An unsuspecting Fritsch was summoned to the Chancellery, where, as if playing a part in a farce, he was confronted by a hired “witness” before a large audience presided over by Hitler. The accusations against Fritsch would soon be proved groundless, but in the meantime they had had the desired effect: instead of merely hurling the “evidence” at Hitler’s feet, as the Führer himself had expected, Fritsch seemed bewildered and confused by the charges. Failing to see through the ploy, he devoted all his efforts over the next few days to erasing the stain on his honor and convincing the Führer that a terrible mistake had been made. Obsessed with his personal disgrace, he rejected all attempts to persuade him to assume a broader perspective and expose the underlying plot, especially by summoning Himmler and Heydrich as witnesses in a court of law. Only after his cause was irretrievably lost did Fritsch realize that the entire affair was aimed not at him personally but at the army as a whole. Thus Hitler spared himself the public confrontation with the armed forces that he had been so eager to avoid.

Fritsch was not the only officer who failed to see that this maneuver was Hitler’s attempt to eliminate all opposition within the army. Lieutenant Colonel Hans Oster of Military Intelligence, who did realize what was going on, attempted to persuade several commanding generals who could mobilize their troops, to demonstrate the military’s might and force Hitler to back down. Ulex in Hannover, Kluge in Münster, and List in Dresden listened in outrage when informed by Oster or his emissaries of the true background to the Fritsch affair; Kluge, it is said, even turned “ash-white.” But no one would take action. The jeering and snickering of those who had plotted the intrigue were almost audible in the background, and it is no wonder that Hitler said he knew for sure now that all generals were cowards. 28

Even more revealing, perhaps, was the reaction of Ludwig Beck, who served briefly as the interim head of army command after Fritsch’s departure. Not only did he provide his former chief with scarcely any support, he forbade the officers in army headquarters to talk about what had happened. When Quartermaster General Franz Halder visited him on January 31 to inquire about the affair, which continued to be a closely guarded secret, Beck stonewalled him, claiming he was duty-bound to remain silent. When Halder demanded that Beck lead his generals in a raid on the Prinz-Albrecht-Strasse headquarters of the Gestapo, which Halder presumed was behind all the intrigues, Beck replied with considerable agitation that this would be nothing less than “mutiny, revolution.” “Such words,” he added, “do not exist in the dictionary of a German officer.” 29The following day Fritsch’s resignation was announced.

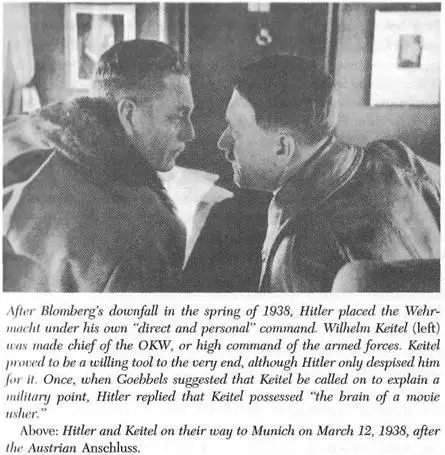

Thus Werner von Fritsch, the commander in chief of the army, was disgraced and quietly driven from his post, though he still felt quite loyal to the Führer. It probably only dawned on Hitler gradually that all the fortuitous events, plotting, and farcical twists of the previous few days had left him with the great opportunity he had always craved: to take a stiff broom to the army. With the first sentence of a decree issued on February 4, 1938, he assumed “direct and personal” command “of the entire Wehrmacht.” Blomberg’s Ministry of War was dissolved and replaced by the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW), or high command of the armed forces. Henceforth the Führer would not have to contend with anyone who spoke for the combined armed forces, just with the commanders of the various branches. At the same time, Hitler took the opportunity to retire or transfer more than sixty generals, in most cases apparently not for any lack of loyalty to the regime but simply in order to bring younger officers to the top. A number of ambassadors received the same treatment. Hitler was certainly at least partially motivated by a desire to shroud the dismissals of Blomberg and Fritsch in a fog of change and reorganization. The extent to which he used this reshuffling to take retribution against those who had opposed him on November 5 of the previous year is indicated by the fact that Neurath, too, was dismissed, to be replaced by Joachim von Ribbentrop. Hitler also put an end to his tempestuous relationship with Hjalmar Schacht, his minister of economics, by appointing Walter Funk to that post. Finally there was the question of what to do with Hermann Göring, whom Hitler named field marshal in an attempt to appease him for having been passed over in this orgy of new appointments.

Thus the last people who could challenge Hitler were eliminated, having been systematically weakened and stripped of their authority. The new men recommended themselves to the Führer through their pliancy and submissiveness, and he expected them to be nothing more than executors of his will. Wilhelm Keitel was made chief of the OKW because Blomberg, during his final interview, had disparaged him as a mere “office manager.” “That’s just the kind of man I need,” Hitler promptly replied. 10Walther von Brauchitsch, who took over as commander in chief after Fritsch, accepted the appointment reluctantly and after long hesitation, more out of a sense of duty than out of ambition. He was apolitical, like many of his fellow generals, tended to avoid conflict, and in any case was much too weak-kneed to have any hope of defending the army’s interests against Hitler, the Nazi Party, and the rising SS.

Hitler’s impatience and the hectic pace of events are almost palpable in the extant documents from this period. Within days of issuing his February 4 decree, he ordered that the matériel needed for army mobilization be “fully” stockpiled by April 1, 1939. Furthermore, he ordered plans to be drafted for a far-reaching naval program that would enable Germany to compete with Great Britain on the high seas and for a fivefold expansion of the Luftwaffe. At the same time, great strides were made on the operational side. Hitler’s heady restlessness of that spring suggests that he was deeply gratified to be free at last of the incessant obstructionism of the old-line generals, with their frowning brows and shaking heads. Now he could pursue his dreams of grandeur and glory unimpeded and “save” the world according to his own vision. On the evening of April 20, 1938, he asked Keitel to head up general staff preparations for the occupation of Czechoslovakia. At about the same time, the chief of general staff, Ludwig Beck, drafted the first of a series of memoranda composed with mounting alarm over the next few months in an attempt to dissuade Hitler from going to war and also to restore the military’s political influence through internal reorganization. That was the beginning of a long, drawn-out duel between unequal opponents. In mid-June Hitler announced that he would take any opportunity that arose after October 1 “to solve the Czech question.”

Although the period between the Röhm and Fritsch affairs was marked by error and blundering, what stands out above all was a lack of will and assertiveness. In its pedantic, exacting way, history almost always requites such failings with shame and humiliation. In the case of Fritsch, not a single general insisted with appropriate vigor on clarifying the circumstances surrounding his denunciation or even on knowing the reasons, which Hitler only vaguely hinted at, that Fritsch could not be fully and publicly exonerated. Still, Brauchitsch interceded persistently and quietly on Fritsch’s behalf and, by pointing to the mounting disquiet in the army, eventually did persuade the Führer to explain himself to the officer corps.

Читать дальше

![Traudl Junge - Hitler's Last Secretary - A Firsthand Account of Life with Hitler [aka Until the Final Hour]](/books/416681/traudl-junge-hitler-s-last-secretary-a-firsthand-thumb.webp)