Herbert Wells - A Short History of the World

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Herbert Wells - A Short History of the World» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, Жанр: История, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Short History of the World

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Short History of the World: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Short History of the World»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A Short History of the World — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Short History of the World», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

But this world of the closing eighteenth century was still only in the interrogative stage in this matter. It had got nothing clear enough, much less settled enough, to act upon. One of its primary impulses was to protect property against the greed and waste of kings and the exploitation of noble adventurers. It was largely to protect private property from taxation that the French Revolution began. But the equalitarian formulæ of the Revolution carried it into a criticism of the very property it had risen to protect. How can men be free and equal when numbers of them have no ground to stand upon and nothing to eat, and the owners will neither feed nor lodge them unless they toil? Excessively—the poor complained.

To which riddle the reply of one important political group was to set about “dividing up.” They wanted to intensify and universalize property. Aiming at the same end by another route, there were the primitive socialists—or, to be more exact, communists—who wanted to “abolish” private property altogether. The state (a democratic state was of course understood) was to own all property.

It is paradoxical that different men seeking the same ends of liberty and happiness should propose on the one hand to make property as absolute as possible, and on the other to put an end to it altogether. But so it was. And the clue to this paradox is to be found in the fact that ownership is not one thing but a multitude of different things.

It was only as the nineteenth century developed that men began to realize that property was not one simple thing, but a great complex of ownerships of different values and consequences, that many things (such as one’s body, the implements of an artist, clothing, toothbrushes) are very profoundly and incurably one’s personal property, and that there is a very great range of things, railways, machinery of various sorts, homes, cultivated gardens, pleasure boats, for example, which need each to be considered very particularly to determine how far and under what limitations it may come under private ownership, and how far it falls into the public domain and may be administered and let out by the state in the collective interest. On the practical side these questions pass into politics, and the problem of making and sustaining efficient state administration. They open up issues in social psychology, and interact with the enquiries of educational science. The criticism of property is still a vast and passionate ferment rather than a science. On the one hand are the Individualists, who would protect and enlarge our present freedoms with what we possess, and on the other the Socialists who would in many directions pool our ownerships and restrain our proprietory acts. In practice one will find every gradation between the extreme individualist, who will scarcely tolerate a tax of any sort to support a government, and the communist who would deny any possessions at all. The ordinary socialist of to-day is what is called a collectivist; he would allow a considerable amount of private property but put such affairs as education, transport, mines, land-owning, most mass productions of staple articles, and the like, into the hands of a highly organized state. Nowadays there does seem to be a gradual convergence of reasonable men towards a moderate socialism scientifically studied and planned. It is realized more and more clearly that the untutored man does not co-operate easily and successfully in large undertakings, and that every step towards a more complex state and every function that the state takes over from private enterprise, necessitates a corresponding educational advance and the organization of a proper criticism and control. Both the press and the political methods of the contemporary state are far too crude for any large extension of collective activities.

But for a time the stresses between employer and employed and particularly between selfish employers and reluctant workers, led to a world-wide dissemination of the very harsh and elementary form of communism which is associated with the name of Marx. Marx based his theories on a belief that men’s minds are limited by their economic necessities, and that there is a necessary conflict of interests in our present civilization between the prosperous and employing classes of people and the employed mass. With the advance in education necessitated by the mechanical revolution, this great employed majority will become more and more class-conscious and more and more solid in antagonism to the (class- conscious) ruling minority. In some way the class-conscious workers would seize power, he prophesied, and inaugurate a new social state. The antagonism, the insurrection, the possible revolution are understandable enough, but it does not follow that a new social state or anything but a socially destructive process will ensue. Put to the test in Russia, Marxism, as we shall note later, has proved singularly uncreative.

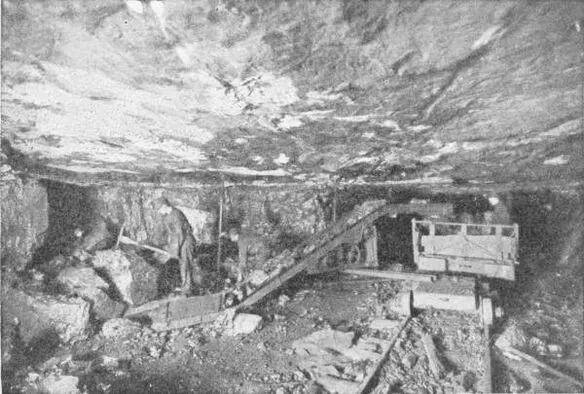

SCIENCE IN THE COAL MINE

Portable Electric Loading Conveyor

Photo: Jeffrey Manufacturing Company, Columbus, Ohio

Marx sought to replace national antagonism by class antagonisms; Marxism has produced in succession a First, a Second and a Third Workers’ International. But from the starting point of modern individualistic thought it is also possible to reach international ideas. From the days of that great English economist, Adam Smith, onward there has been an increasing realization that for world-wide prosperity free and unencumbered trade about the earth is needed. The individualist with his hostility to the state is hostile also to tariffs and boundaries and all the restraints upon free act and movement that national boundaries seem to justify. It is interesting to see two lines of thought, so diverse in spirit, so different in substance as this class-war socialism of the Marxists and the individualistic free-trading philosophy of the British business men of the Victorian age heading at last, in spite of these primary differences, towards the same intimations of a new world-wide treatment of human affairs outside the boundaries and limitations of any existing state. The logic of reality triumphs over the logic of theory. We begin to perceive that from widely divergent starting points individualist theory and socialist theory are part of a common search, a search for more spacious social and political ideas and interpretations, upon which men may contrive to work together, a search that began again in Europe and has intensified as men’s confidence in the ideas of the Holy Roman Empire and in Christendom decayed, and as the age of discovery broadened their horizons from the world of the Mediterranean to the whole wide world.

To bring this description of the elaboration and development of social, economic and political ideas right down to the discussions of the present day, would be to introduce issues altogether too controversial for the scope and intentions of this book. But regarding these things, as we do here, from the vast perspectives of the student of world history, we are bound to recognize that this reconstruction of these directive ideas in the human mind is still an unfinished task—we cannot even estimate yet how unfinished the task may be. Certain common beliefs do seem to be emerging, and their influence is very perceptible upon the political events and public acts of to-day; but at present they are not clear enough nor convincing enough to compel men definitely and systematically towards their realization. Men’s acts waver between tradition and the new, and on the whole they rather gravitate towards the traditional. Yet, compared with the thought of even a brief lifetime ago, there does seem to be an outline shaping itself of a new order in human affairs. It is a sketchy outline, vanishing into vagueness at this point and that, and fluctuating in detail and formulæ, yet it grows steadfastly clearer, and its main lines change less and less.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Short History of the World»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Short History of the World» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Short History of the World» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.