Herbert Wells - A Short History of the World

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Herbert Wells - A Short History of the World» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, Жанр: История, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Short History of the World

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Short History of the World: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Short History of the World»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A Short History of the World — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Short History of the World», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The German religious war began in 1546, a few months after the death of Martin Luther. We need not trouble about the incidents of the campaign. The Protestant Saxon army was badly beaten at Lochau. By something very like a breach of faith Philip of Hesse, the Emperor’s chief remaining antagonist, was caught and imprisoned, and the Turks were bought off by the promise of an annual tribute. In 1547, to the great relief of the Emperor, Francis I died. So by 1547 Charles got to a kind of settlement, and made his last efforts to effect peace where there was no peace. In 1552 all Germany was at war again, only a precipitate flight from Innsbruck saved Charles from capture, and in 1552, with the treaty of Passau, came another unstable equilibrium ....

Such is the brief outline of the politics of the Empire for thirty-two years. It is interesting to note how entirely the European mind was concentrated upon the struggle for European ascendancy. Neither Turks, French, English nor Germans had yet discovered any political interest in the great continent of America, nor any significance in the new sea routes to Asia. Great things were happening in America; Cortez with a mere handful of men had conquered the great Neolithic empire of Mexico for Spain, Pizarro had crossed the Isthmus of Panama (1530) and subjugated another wonder-land, Peru. But as yet these events meant no more to Europe than a useful and stimulating influx of silver to the Spanish treasury.

It was after the treaty of Passau that Charles began to display his distinctive originality of mind. He was now entirely bored and disillusioned by his imperial greatness. A sense of the intolerable futility of these European rivalries came upon him. He had never been of a very sound constitution, he was naturally indolent and he was suffering greatly from gout. He abdicated. He made over all his sovereign rights in Germany to his brother Ferdinand, and Spain and the Netherlands he resigned to his son Philip. Then in a sort of magnificent dudgeon he retired to a monastery at Yuste, among the oak and chestnut forests in the hills to the north of the Tagus valley. There he died in 1558.

Much has been written in a sentimental vein of this retirement, this renunciation of the world by this tired majestic Titan, world-weary, seeking in an austere solitude his peace with God. But his retreat was neither solitary nor austere; he had with him nearly a hundred and fifty attendants: his establishment had all the splendour and indulgences without the fatigues or a court, and Philip II was a dutiful son to whom his father’s advice was a command.

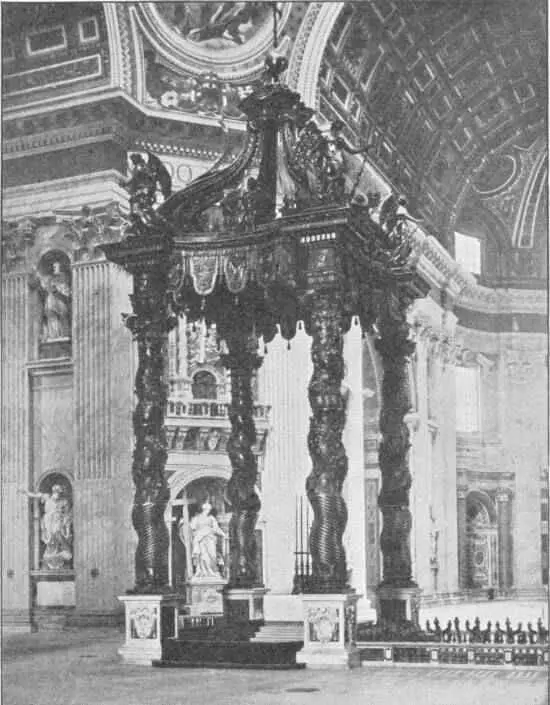

INTERIOR OF ST. PETER’S, ROME, SHOWING THE HIGH ALTAR

Photo: Alinari

And if Charles had lost his living interest in the administration of European affairs, there were other motives of a more immediate sort to stir him. Says Prescott: “In the almost daily correspondence between Quixada, or Gaztelu, and the Secretary of State at Valladolid, there is scarcely a letter that does not turn more or less on the Emperor’s eating or his illness. The one seems naturally to follow, like a running commentary, on the other. It is rare that such topics have formed the burden of communications with the department of state. It must have been no easy matter for the secretary to preserve his gravity in the perusal of despatches in which politics and gastronomy were so strangely mixed together. The courier from Valladolid to Lisbon was ordered to make a detour, so as to take Jarandilla in his route, and bring supplies to the royal table. On Thursdays he was to bring fish to serve for the jour maigre that was to follow. The trout in the neighbourhood Charles thought too small, so others of a larger size were to be sent from Valladolid. Fish of every kind was to his taste, as, indeed, was anything that in its nature or habits at all approached to fish. Eels, frogs, oysters, occupied an important place in the royal bill of fare. Potted fish, especially anchovies, found great favour with him; and he regretted that he had not brought a better supply of these from the Low Countries. On an eel-pasty he particularly doted.” ... [1]

In 1554 Charles had obtained a bull from Pope Julius III granting him a dispensation from fasting, and allowing him to break his fast early in the morning even when he was to take the sacrament.

Eating and doctoring! it was a return to elemental things. He had never acquired the habit of reading, but he would be read aloud to at meals after the fashion of Charlemagne, and would make what one narrator describes as a “sweet and heavenly commentary.” He also amused himself with mechanical toys, by listening to music or sermons, and by attending to the imperial business that still came drifting in to him. The death of the Empress, to whom he was greatly attached, had turned his mind towards religion, which in his case took a punctilious and ceremonial form; every Friday in Lent he scourged himself with the rest of the monks with such good will as to draw blood. These exercises and the gout released a bigotry in Charles that had hitherto been restrained by considerations of policy. The appearance of Protestant teaching close at hand in Valladolid roused him to fury. “Tell the grand inquisitor and his council from me to be at their posts, and to lay the axe at the root of the evil before it spreads further.” . .. He expressed a doubt whether it would not be well, in so black an affair, to dispense with the ordinary course of justice, and to show no mercy; “lest the criminal, if pardoned, should have the opportunity of repeating his crime.” He recommended, as an example, his own mode or proceeding in the Netherlands, “where all who remained obstinate in their errors were burned alive, and those who were admitted to penitence were beheaded.”

And almost symbolical of his place and role in history was his preoccupation with funerals. He seems to have had an intuition that something great was dead in Europe and sorely needed burial, that there was a need to write Finis, overdue. He not only attended every actual funeral that was celebrated at Yuste, but he had services conducted for the absent dead, he held a funeral service in memory of his wife on the anniversary of her death, and finally he celebrated his own obsequies.

“The chapel was hung with black, and the blaze of hundreds of wax-lights was scarcely sufficient to dispel the darkness. The brethren in their conventual dress, and all the Emperor’s household clad in deep mourning, gathered round a huge catafalque, shrouded also in black, which had been raised in the centre of the chapel. The service for the burial of the dead was then performed; and, amidst the dismal wail of the monks, the prayers ascended for the departed spirit, that it might be received into the mansions of the blessed. The sorrowful attendants were melted to tears, as the image of their master’s death was presented to their minds—or they were touched, it may be, with compassion by this pitiable display of weakness. Charles, muffled in a dark mantle, and bearing a lighted candle in his hand, mingled with his household, the spectator of his own obsequies; and the doleful ceremony was concluded by his placing the taper in the hands of the priest, in sign of his surrendering up his soul to the Almighty.”

Within two months of this masquerade he was dead. And the brief greatness of the Holy Roman Empire died with him. His realm was already divided between his brother and his son. The Holy Roman Empire struggled on indeed to the days of Napoleon I but as an invalid and dying thing. To this day its unburied tradition still poisons the political air.

[1] Prescott’s Appendix to Robertson’s History of Charles V .

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Short History of the World»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Short History of the World» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Short History of the World» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.