Herbert Wells - A Short History of the World

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Herbert Wells - A Short History of the World» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, Жанр: История, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Short History of the World

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Short History of the World: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Short History of the World»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A Short History of the World — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Short History of the World», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

His greatness was not of his own making. It was largely the creation of his grandfather, the Emperor Maximilian I (1459- 1519). Some families have fought, others have intrigued their way to world power; the Habsburgs married their way. Maximilian began his career with Austria, Styria, part of Alsace and other districts, the original Habsburg patrimony; he married—the lady’s name scarcely matters to us—the Netherlands and Burgundy. Most of Burgundy slipped from him after his first wife’s death, but the Netherlands he held. Then he tried unsuccessfully to marry Brittany. He became Emperor in succession to his father, Frederick III, in 1493, and married the duchy of Milan. Finally he married his son to the weak-minded daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella, the Ferdinand and Isabella of Columbus, who not only reigned over a freshly united Spain and over Sardinia and the kingdom of the two Sicilies, but over all America west of Brazil. So it was that this Charles V, his grandson, inherited most of the American continent and between a third and a half of what the Turks had left of Europe. He succeeded to the Netherlands in 1506. When his grandfather Ferdinand died in 1516, he became practically king of the Spanish dominions, his mother being imbecile; and his grandfather Maximilian dying in 1519, he was in 1520 elected Emperor at the still comparatively tender age of twenty.

He was a fair young man with a not very intelligent face, a thick upper lip and a long clumsy chin. He found himself in a world of young and vigorous personalities. It was an age of brilliant young monarchs. Francis I had succeeded to the French throne in 1515 at the age of twenty-one, Henry VIII had become King of England in 1509 at eighteen. It was the age of Baber in India (1526-1530) and Suleiman the Magnificent in Turkey (1520), both exceptionally capable monarchs, and the Pope Leo X (1513) was also a very distinguished Pope. The Pope and Francis I attempted to prevent the election of Charles as Emperor because they dreaded the concentration of so much power in the hands of one man. Both Francis I and Henry VIII offered themselves to the imperial electors. But there was now a long established tradition of Habsburg Emperors (since 1273), and some energetic bribery secured the election for Charles.

At first the young man was very much a magnificent puppet in the hands of his ministers. Then slowly he began to assert himself and take control. He began to realize something of the threatening complexities of his exalted position. It was a position as unsound as it was splendid.

From the very outset of his reign he was faced by the situation created by Luther’s agitations in Germany. The Emperor had one reason for siding with the reformers in the opposition of the Pope to his election. But he had been brought up in Spain, that most Catholic of countries, and he decided against Luther. So he came into conflict with the Protestant princes and particularly the Elector of Saxony. He found himself in the presence of an opening rift that was to split the outworn fabric of Christendom into two contending camps. His attempts to close that rift were strenuous and honest and ineffective. There was an extensive peasant revolt in Germany which interwove with the general political and religious disturbance. And these internal troubles were complicated by attacks upon the Empire from east and west alike. On the west of Charles was his spirited rival, Francis I; to the east was the ever advancing Turk, who was now in Hungary, in alliance with Francis and clamouring for certain arrears of tribute from the Austrian dominions. Charles had the money and army of Spain at his disposal, but it was extremely difficult to get any effective support in money from Germany. His social and political troubles were complicated by financial distresses. He was forced to ruinous borrowing.

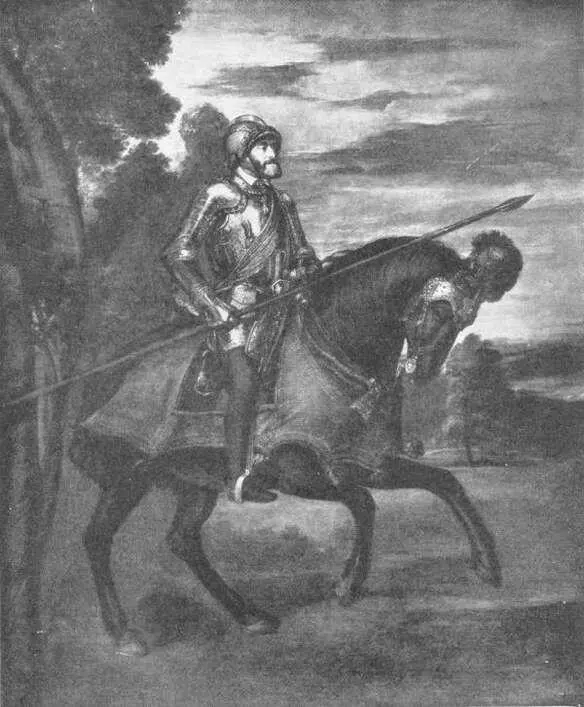

THE CHARLES V PORTRAIT BY TITIAN

(In the Gallery del Prado, Madrid)

Photo: Anderson

On the whole, Charles, in alliance with Henry VIII, was successful against Francis I and the Turk. Their chief battlefield was North Italy; the generalship was dull on both sides; their advances and retreats depended mainly on the arrival of reinforcements. The German army invaded France, failed to take Marseilles, fell back into Italy, lost Milan, and was besieged in Pavia. Francis I made a long and unsuccessful siege of Pavia, was caught by fresh German forces, defeated, wounded and taken prisoner. But thereupon the Pope and Henry VIII, still haunted by the fear of his attaining excessive power, turned against Charles. The German troops in Milan, under the Constable of Bourbon, being unpaid, forced rather than followed their commander into a raid upon Rome. They stormed the city and pillaged it (1527). The Pope took refuge in the Castle of St. Angelo while the looting and slaughter went on. He bought off the German troops at last by the payment of four hundred thousand ducats. Ten years of such confused fighting impoverished all Europe. At last the Emperor found himself triumphant in Italy. In 1530, he was crowned by the Pope—he was the last German Emperor to be so crowned—at Bologna.

Meanwhile the Turks were making great headway in Hungary. They had defeated and killed the king of Hungary in 1526, they held Buda-Pesth, and in 1529 Suleiman the Magnificent very nearly took Vienna. The Emperor was greatly concerned by these advances, and did his utmost to drive back the Turks, but he found the greatest difficulty in getting the German princes to unite even with this formidable enemy upon their very borders. Francis I remained implacable for a time, and there was a new French war; but in 1538 Charles won his rival over to a more friendly attitude after ravaging the south of France. Francis and Charles then formed an alliance against the Turk. But the Protestant princes, the German princes who were resolved to break away from Rome, had formed a league, the Schmalkaldic League, against the Emperor, and in the place of a great campaign to recover Hungary for Christendom Charles had to turn his mind to the gathering internal struggle in Germany. Of that struggle he saw only the opening war. It was a struggle, a sanguinary irrational bickering of princes, for ascendancy, now flaming into war and destruction, now sinking back to intrigues and diplomacies; it was a snake’s sack of princely policies that was to go on writhing incurably right into the nineteenth century and to waste and desolate Central Europe again and again.

The Emperor never seems to have grasped the true forces at work in these gathering troubles. He was for his time and station an exceptionally worthy man, and he seems to have taken the religious dissensions that were tearing Europe into warring fragments as genuine theological differences. He gathered diets and councils in futile attempts at reconciliation. Formulæ and confessions were tried over. The student of German history must struggle with the details of the Religious Peace of Nuremberg, the settlement at the Diet of Ratisbon, the Interim of Augsburg, and the like. Here we do but mention them as details in the worried life of this culminating Emperor. As a matter of fact, hardly one of the multifarious princes and rulers in Europe seems to have been acting in good faith. The widespread religious trouble of the world, the desire of the common people for truth and social righteousness, the spreading knowledge of the time, all those things were merely counters in the imaginations of princely diplomacy. Henry VIII of England, who had begun his career with a book against heresy, and who had been rewarded by the Pope with the title of “Defender of the Faith,” being anxious to divorce his first wife in favour of a young lady named Anne Boleyn, and wishing also to loot the vast wealth of the church in England, joined the company of Protestant princes in 1530. Sweden, Denmark and Norway had already gone over to the Protestant side.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Short History of the World»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Short History of the World» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Short History of the World» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.