Herbert Wells - A Short History of the World

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Herbert Wells - A Short History of the World» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, Жанр: История, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Short History of the World

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Short History of the World: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Short History of the World»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A Short History of the World — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Short History of the World», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

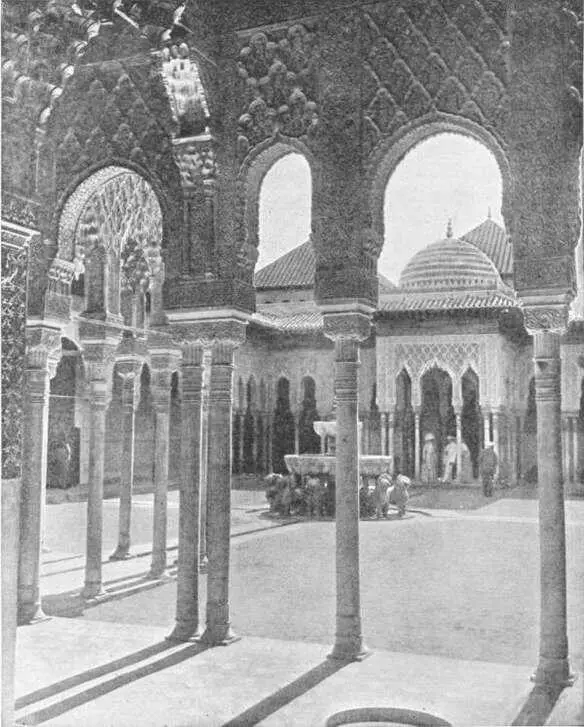

A COURTYARD IN THE ALHAMBRA

Photo: Lehnert & Landrock

In those centuries a simple Christian faith was real and widespread over great areas of Europe. Rome itself had passed through some dark and discreditable phases; few writers can be found to excuse the lives of Popes John XI and John XII in the tenth century; they were abominable creatures; but the heart and body of Latin Christendom had remained earnest and simple; the generality of the common priests and monks and nuns had lived exemplary and faithful lives. Upon the wealth of confidence such lives created rested the power of the church. Among the great Popes of the past had been Gregory the Great, Gregory I (590-604) and Leo III (795-816) who invited Charlemagne to be Cæsar and crowned him in spite of himself. Towards the close of the eleventh century there arose a great clerical statesman, Hildebrand, who ended his life as Pope Gregory VII (1073- 1085). Next but one after him came Urban II (1087-1099), the Pope of the First Crusade. These two were the founders of this period of papal greatness during which the Popes lorded it over the Emperors. From Bulgaria to Ireland and from Norway to Sicily and Jerusalem the Pope was supreme. Gregory VII obliged the Emperor Henry IV to come in penitence to him at Canossa and to await forgiveness for three days and nights in the courtyard of the castle, clad in sackcloth and barefooted to the snow. In 1176 at Venice the Emperor Frederick (Frederick Barbarossa), knelt to Pope Alexander III and swore fealty to him.

The great power of the church in the beginning of the eleventh century lay in the wills and consciences of men. It failed to retain the moral prestige on which its power was based. In the opening decades of the fourteenth century it was discovered that the power of the Pope had evaporated. What was it that destroyed the naive confidence of the common people of Christendom in the church so that they would no longer rally to its appeal and serve its purposes?

The first trouble was certainly the accumulation of wealth by the church. The church never died, and there was a frequent disposition on the part of dying childless people to leave lands to the church. Penitent sinners were exhorted to do so. Accordingly in many European countries as much as a fourth of the land became church property. The appetite for property grows with what it feeds upon. Already in the thirteenth century it was being said everywhere that the priests were not good men, that they were always hunting for money and legacies.

The kings and princes disliked this alienation of property very greatly. In the place of feudal lords capable of military support, they found their land supporting abbeys and monks and nuns. And these lands were really under foreign dominion. Even before the time of Pope Gregory VII there had been a struggle between the princes and the papacy over the question of “investitures,” the question that is of who should appoint the bishops. If that power rested with the Pope and not the King, then the latter lost control not only of the consciences of his subjects but of a considerable part of his dominions. For also the clergy claimed exemption from taxation. They paid their taxes to Rome. And not only that, but the church also claimed the right to levy a tax of one-tenth upon the property of the layman in addition to the taxes he paid his prince.

The history of nearly every country in Latin Christendom tells of the same phase in the eleventh century, a phase of struggle between monarch and Pope on the issue of investitures and generally it tells of a victory for the Pope. He claimed to be able to excommunicate the prince, to absolve his subjects from their allegiance to him, to recognize a successor. He claimed to be able to put a nation under an interdict, and then nearly all priestly functions ceased except the sacraments of baptism, confirmation and penance; the priests could neither hold the ordinary services, marry people, nor bury the dead. With these two weapons it was possible for the twelfth century Popes to curb the most recalcitrant princes and overawe the most restive peoples. These were enormous powers, and enormous powers are only to be used on extraordinary occasions. The Popes used them at last with a frequency that staled their effect. Within thirty years at the end of the twelfth century we find Scotland, France and England in turn under an interdict. And also the Popes could not resist the temptation to preach crusades against offending princes—until the crusading spirit was extinct.

It is possible that if the Church of Rome had struggled simply against the princes and had had a care to keep its hold upon the general mind, it might have achieved a permanent dominion over all Christendom. But the high claims of the Pope were reflected as arrogance in the conduct of the clergy. Before the eleventh century the Roman priests could marry; they had close ties with the people among whom they lived; they were indeed a part of the people. Gregory VII made them celibates; he cut the priests off from too great an intimacy with the laymen in order to bind them more closely to Rome, but indeed he opened a fissure between the church and the commonalty. The church had its own law courts. Cases involving not merely priests but monks, students, crusaders, widows, orphans and the helpless were reserved for the clerical courts, and so were all matters relating to wills, marriages and oaths and all cases of sorcery, heresy and blasphemy. Whenever the layman found himself in conflict with the priest he had to go to a clerical court. The obligations of peace and war fell upon his shoulders alone and left the priest free. It is no great wonder that jealousy and hatred of the priests grew up in the Christian world.

Never did Rome seem to realize that its power was in the consciences of common men. It fought against religious enthusiasm, which should have been its ally, and it forced doctrinal orthodoxy upon honest doubt and aberrant opinion. When the church interfered in matters of morality it had the common man with it, but not when it interfered in matters of doctrine. When in the south of France Waldo taught a return to the simplicity of Jesus in faith and life, Innocent III preached a crusade against the Waldenses, Waldo’s followers, and permitted them to be suppressed with fire, sword, rape and the most abominable cruelties. When again St. Francis of Assisi (1181-1226) taught the imitation of Christ and a life of poverty and service, his followers, the Franciscans, were persecuted, scourged, imprisoned and dispersed. In 1318 four of them were burnt alive at Marseilles. On the other hand the fiercely orthodox order of the Dominicans, founded by St. Dominic (1170-1221) was strongly supported by Innocent III, who with its assistance set up an organization, the Inquisition, for the hunting of heresy and the affliction of free thought.

So it was that the church by excessive claims, by unrighteous privileges, and by an irrational intolerance destroyed that free faith of the common man which was the final source of all its power. The story of its decline tells of no adequate foemen from without but continually of decay from within.

XLVII

RECALCITRANT PRINCES AND THE GREAT SCHISM

ONE very great weakness of the Roman Church in its struggle to secure the headship of all Christendom was the manner in which the Pope was chosen.

If indeed the papacy was to achieve its manifest ambition and establish one rule and one peace throughout Christendom, then it was vitally necessary that it should have a strong, steady and continuous direction. In those great days of its opportunity it needed before all things that the Popes when they took office should be able men in the prime of life, that each should have his successor-designate with whom he could discuss the policy of the church, and that the forms and processes of election should be clear, definite, unalterable and unassailable. Unhappily none of these things obtained. It was not even clear who could vote in the election of a Pope, nor whether the Byzantine or Holy Roman Emperor had a voice in the matter. That very great papal statesman Hildebrand (Pope Gregory VII, 1073-1085) did much to regularize the election. He confined the votes to the Roman cardinals and he reduced the Emperor’s share to a formula of assent conceded to him by the church, but he made no provision for a successor-designate and he left it possible for the disputes of the cardinals to keep the See vacant, as in some cases it was kept vacant, for a year or more.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Short History of the World»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Short History of the World» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Short History of the World» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.