Herbert Wells - A Short History of the World

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Herbert Wells - A Short History of the World» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, Жанр: История, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Short History of the World

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Short History of the World: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Short History of the World»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A Short History of the World — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Short History of the World», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The Byzantine emperor, Michael VII, was overcome with terror. He was already heavily engaged in warfare with a band of Norman adventurers who had seized Durazzo, and with a fierce Turkish people, the Petschenegs, who were raiding over the Danube. In his extremity he sought help where he could, and it is notable that he did not appeal to the western emperor but to the Pope of Rome as the head of Latin Christendom. He wrote to Pope Gregory VII, and his successor Alexius Comnenus wrote still more urgently to Urban II.

CRUSADER TOMBS IN EXETER CATHEDRAL

Photo: Mansell

This was not a quarter of a century from the rupture of the Latin and Greek churches. That controversy was still vividly alive in men’s minds, and this disaster to Byzantium must have presented itself to the Pope as a supreme opportunity for reasserting the supremacy of the Latin Church over the dissentient Greeks. Moreover this occasion gave the Pope a chance to deal with two other matters that troubled western Christendom very greatly. One was the custom of “private war” which disordered social life, and the other was the superabundant fighting energy of the Low Germans and Christianized Northmen and particularly of the Franks and Normans. A religious war, the Crusade, the War of the Cross, was preached against the Turkish captors of Jerusalem, and a truce to all warfare amongst Christians (1095). The declared object of this war was the recovery of the Holy Sepulchre from the unbelievers. A man called Peter the Hermit carried on a popular propaganda throughout France and Germany on broadly democratic lines. He went clad in a coarse garment, barefooted on an ass, he carried a huge cross and harangued the crowd in street or market-place or church. He denounced the cruelties practised upon the Christian pilgrims by the Turks, and the shame of the Holy Sepulchre being in any but Christian hands. The fruits of centuries of Christian teaching became apparent in the response. A great wave of enthusiasm swept the western world, and popular Christendom discovered itself.

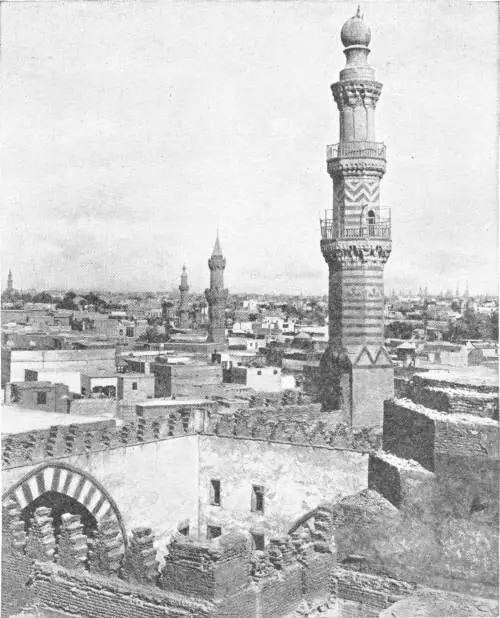

VIEW OF CAIRO

Photo: Lehnert & Landrock

Such a widespread uprising of the common people in relation to a single idea as now occurred was a new thing in the history of our race. There is nothing to parallel it in the previous history of the Roman Empire or of India or China. On a smaller scale, however, there had been similar movements among the Jewish people after their liberation from the Babylonian captivity, and later on Islam was to display a parallel susceptibility to collective feeling. Such movements were certainly connected with the new spirit that had come into life with the development of the missionary- teaching religions. The Hebrew prophets, Jesus and his disciples, Mani, Muhammad, were all exhorters of men’s individual souls. They brought the personal conscience face to face with God. Before that time religion had been much more a business of fetish, of pseudoscience, than of conscience. The old kind of religion turned upon temple, initiated priest and mystical sacrifice, and ruled the common man like a slave by fear. The new kind of religion made a man of him.

The preaching of the First Crusade was the first stirring of the common people in European history. It may be too much to call it the birth of modern democracy, but certainly at that time modern democracy stirred. Before very long we shall find it stirring again, and raising the most disturbing social and religious questions.

Certainly this first stirring of democracy ended very pitifully and lamentably. Considerable bodies of common people, crowds rather than armies, set out eastward from France and the Rhineland and Central Europe without waiting for leaders or proper equipment to rescue the Holy Sepulchre. This was the “people’s crusade.” Two great mobs blundered into Hungary, mistook the recently converted Magyars for pagans, committed atrocities and were massacred. A third multitude with a similarly confused mind, after a great pogrom of the Jews in the Rhineland, marched eastward, and was also destroyed in Hungary. Two other huge crowds, under the leadership of Peter the Hermit himself, reached Constantinople, crossed the Bosphorus, and were massacred rather than defeated by the Seljuk Turks. So began and ended this first movement of the European people, as people.

Next year (1097) the real fighting forces crossed the Bosphorus. Essentially they were Norman in leadership and spirit. They stormed Nicæa, marched by much the same route as Alexander had followed fourteen centuries before, to Antioch. The siege of Antioch kept them a year, and in June 1099 they invested Jerusalem. It was stormed after a month’s siege. The slaughter was terrible. Men riding on horseback were splashed by the blood in the streets. At nightfall on July 15th the Crusaders had fought their way into the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and overcome all opposition there: blood-stained, weary and “sobbing from excess of joy” they knelt down in prayer.

THE HORSES OF S. MARK, VENICE

Originally on the arch of Trajan at Constantinople, the Doge Dandalo V took them after the Fourth Crusade, to Venice, whence Napoleon I removed them to Paris, but in 1815 they were returned to Venice. During the Great War of 1914-18 they were hidden away for fear of air raids.

Photo: D. McLeish

Immediately the hostility of Latin and Greek broke out again. The Crusaders were the servants of the Latin Church, and the Greek patriarch of Jerusalem found himself in a far worse case under the triumphant Latins than under the Turks. The Crusaders discovered themselves between Byzantine and Turk and fighting both. Much of Asia Minor was recovered by the Byzantine Empire, and the Latin princes were left, a buffer between Turk and Greek, with Jerusalem and a few small principalities, of which Edessa was one of the chief, in Syria. Their grip even on these possessions was precarious, and in 1144 Edessa fell to the Moslim, leading to an ineffective Second Crusade, which failed to recover Edessa but saved Antioch from a similar fate.

In 1169 the forces of Islam were rallied under a Kurdish adventurer named Saladin who had made himself master of Egypt. He preached a Holy War against the Christians, recaptured Jerusalem in 1187, and so provoked the Third Crusade. This failed to recover Jerusalem. In the Fourth Crusade (1202-4) the Latin Church turned frankly upon the Greek Empire, and there was not even a pretence of fighting the Turks. It started from Venice and in 1204 it stormed Constantinople. The great rising trading city of Venice was the leader in this adventure, and most of the coasts and islands of the Byzantine Empire were annexed by the Venetians. A “Latin” emperor (Baldwin of Flanders) was set up in Constantinople and the Latin and Greek Church were declared to be reunited. The Latin emperors ruled in Constantinople from 1204 to 1261 when the Greek world shook itself free again from Roman predominance.

The twelfth century then and the opening of the thirteenth was the age of papal ascendancy just as the eleventh was the age of the ascendancy of the Seljuk Turks and the tenth the age of the Northmen. A united Christendom under the rule of the Pope came nearer to being a working reality than it ever was before or after that time.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Short History of the World»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Short History of the World» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Short History of the World» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.