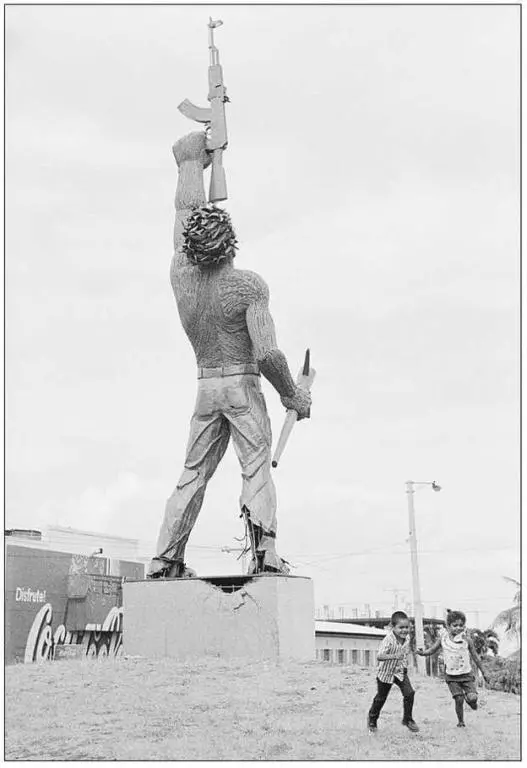

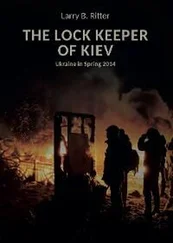

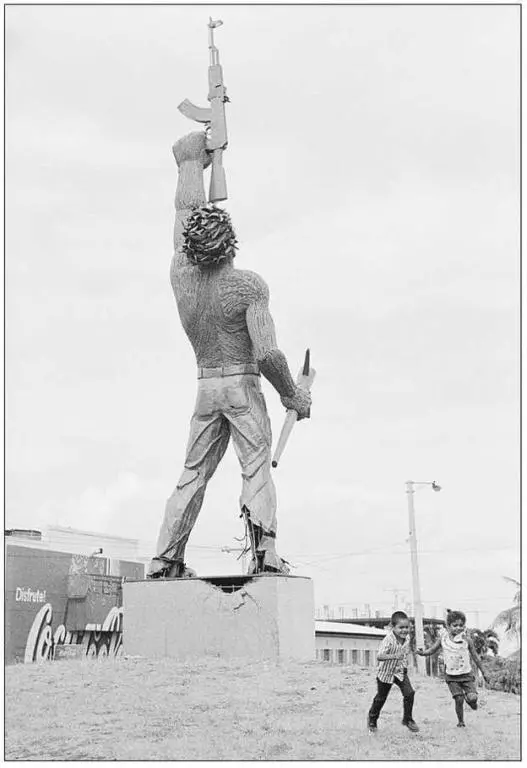

Because of his exaggerated muscle-rippled chest, this statue of a Sandinista guerrilla was dubbed the Incredible Hulk by locals, who employ the comic-book hero’s name to direct tourists, telling them to “take a right at the Incredible Hulk.” At the base of this landmark, erected to honor the freedom fighters who drove out the Somoza-family dictators, are inscribed the words of General Augusto Sandino, for whom the Sandinistas are named: In the end, only the workers and peasants will remain .

Sandino got it partly right.

Along with the workers and peasants are tens of thousands of unaccounted-for AKs left over from the country’s forty years of strife that spilled over into neighboring Honduras and El Salvador and caused Kalashnikov Cultures to spring up in Peru, Colombia, and Venezuela. Like Kalashnikov Cultures in the Middle East, these are just as ingrained and just as deadly.

In Nicaragua’s capital of Managua, this statue of a Sandinista guerrilla thrusting an AK skyward was erected to honor the freedom fighters who drove out the Somoza-family dictators. Because of its exaggerated muscle-rippled chest, the locals dubbed it the Incredible Hulk after the comic-book hero. © 1999, James Lerager

Despite government initiatives to disarm citizens and destroy weapons, most are still around, and with new weapons pouring into the region daily from around the world, parts of some Central and South American countries remain gun-heavy and dangerous.

Unlike Africa, where AK-toting, poorly disciplined gangs mainly engaged in small-time subsistence looting, pillaging villages and supporting despots like Charles Taylor in his gun and blood-diamond trade, the Latin American scene evolved from violent civil wars between rebel groups and government forces to powerful, well-trained and disciplined drug cartels that operate under the guise of political ideology.

These groups are so rich and powerful that they mimic small countries, maintaining order in their strongholds, taxing drug farmers, and keeping government forces at bay. Their political ideologies, both right- and left-wing, exist mainly as the glue that supports a social, economic, and cultural infrastructure focused on growing, smuggling, and profiting from illegal drugs such as cocaine and heroin. (Afghanistan remains the largest producer of heroin, its exports reaching the United States through drug smuggling routes established and protected by South American drug cartels.)

As these groups grew stronger, they were able to purchase larger weapons—one Colombian drug cartel even had a submarine on the drawing board to smuggle cocaine—but their work-horse remains the AK, which is often paid for with drugs instead of money. This barter was so institutionalized that a de facto exchange rate of one kilo of cocaine sulfate per AK was established. (Cocaine sulfate is produced by mashing coca leaves with water and dilute sulfuric acid. This produces an easily transportable paste that is an intermediate step to producing cocaine hydrochloride—common street cocaine.)

As the civil wars in Nicaragua, El Salvador, and Guatemala petered out in the 1990s because of exhaustion by the combatants, tens of thousands of small arms, mainly AKs, remained in the hands of former rebels and government soldiers who used them in criminal acts ranging from robbery and homicide to protection for South American drug cartels that employed Central America as a waypoint for contraband heading north to the United States. Currently, more than 70 percent of the cocaine entering the United States comes through the Central America-Mexico border, according to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, and governments weakened by civil wars and ensuing domestic violence often are powerless to stop the traffic.

These civil wars, fueled by AKs supplied by the two superpowers, have left Central America as one of the most violent regions in the world, with crime rates more than double the world average. These crime rates not only impede democratic processes but have locked the region in widespread poverty. The Inter-American Development Bank estimates that Latin America’s per capita gross domestic product would be 25 percent higher if the crime rate were more in line with the world average.

LIKE AFGHANISTAN, NICARAGUA became its hemisphere’s premier entry point for AKs. In almost parallel fashion, the U.S. government, wanting to fight pro-Soviet regimes, covertly armed Nicaraguan Contra fighters with AKs manufactured by Warsaw Pact countries. The Soviets did the same for their comrades.

Drugs, AKs, and political dogma are so tightly bound together in this region of the world that they may never be unwound. Unless they are, however, the three will feed on each other as Latin American nations remain mired in the chaos of government corruption, violence, and severe urban poverty.

This deadly triad in Central America can be traced to U.S. intervention in Nicaragua in the 1850s when the conservative elite of the city of León invited American adventurer William Walker to fight against their rivals, the liberal elite of Granada. Remarkably, Walker was elected president in 1856, but forces from neighboring Honduras and other countries drove him out and later executed him.

From 1912 through 1933, except for one nine-month period, U.S. Marines were stationed in Nicaragua; the U.S. administrations said they were needed to protect American citizens and property. From 1927 to 1933, Sandino led a revolt against the conservative regime and their U.S. supporters, and U.S. troops finally left in 1933, but not before they had set up the National Guard, a militia designed to look after U.S. economic interests after the marines’ exit. Anastasio Somoza Garcia was put in charge of the National Guard, and he ruled the country along with Sandino and President Carlos Alberto Brenes Jarquin, a figurehead politician. Half a century later, the fragments of this National Guard would became the focal point of U.S.-supplied AKs.

With U.S. support, Somoza Garcia took full control of the country, and the National Guard assassinated Sandino in 1934. The Somoza clan held dictatorial power through torture, intimidation, and military force until 1979. During the family’s reign, which was passed along to sons and brothers, they built an enormous fortune through bribery, exports of coffee, cattle, cotton, and timber, and by accepting financial and military aid from the United States—as long as they remained anti-Communist. Like Charles Taylor in Liberia, the Somozas ran Nicaragua for their own personal benefit.

Opposition was building, however. Buoyed by the success of the Communist revolution against Cuban dictator General Fulgencio Batista in 1961, Sandinista forces backed by Cuba staged raids from Honduras and Costa Rica against Somoza’s National Guard troops. Although Cuba did not produce AKs, it received them from the Soviet Union and Warsaw Pact countries as well as North Korea and supplied them to rebel forces in Nicaragua. Aside from hunting rifles and other scrounged firearms, the AK became the Sandinistas’ main weapon. Cuba had previously backed pro-Communist rebels in Angola with weapons, funding, and troops and was doing the same for the Sandinistas despite protests from the United States.

U.S. officials were torn. On one side was a dictatorship that was growing more brutal as the revolutionaries became more active. On the other side was the specter of the Soviet Union gaining a foothold in Nicaragua as it had done in Cuba. The United States continued to support Somoza with funds and weapons until December 1972, when an earthquake destroyed much of Managua, killing ten thousand people, leaving fifty thousand families homeless, and ruining about 80 percent of the city’s commercial buildings.

Читать дальше