There is also evidence of a so-called genocide fax sent to UN headquarters in New York that outlines plans for mass killings, but this document has been discredited by many as a hoax, another attempt to bolster support for the RPF among Western nations.

One of the ironies of the genocide was that Kagame and his 12,000-strong RPF defeated the FAR and Hutu paramilitary groups with no artillery, aircraft, or armored vehicles. Their main weapon was the AK. In his best-selling book We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed with Our Families , author Philip Gourevitch noted this about Kagame: “That he had pulled it off [the defeat of FAR and the end of genocide] with an arsenal composed merely of mortars, rocked propelled grenades and, primarily, what one American arms specialist described to me as ‘piece of shit’ secondhand Kalashnikovs, has only added to the [Kagame] legend. ‘The problem isn’t the equipment,’ Kagame said, ‘the problem is always the man behind it.’”

Whether the Rwandan war turns out to have been a true tribal conflict, a war perpetrated by Western nations, or a combination of these factors, one thing is certain: the AK was the main fuel that fed this terrible tragedy.

RWANDA AND OTHER COUNTRIES in Africa make up just a small part of a long list of devastation brought about by the AK and other small arms. In some countries, people half jokingly call the AK the “African Credit Card,” because in many parts of the continent having one is necessary for everyday existence. In Angola, for example, refugees and former rebels fleeing from government forces during their civil war traded AKs to Zambian villagers for food.

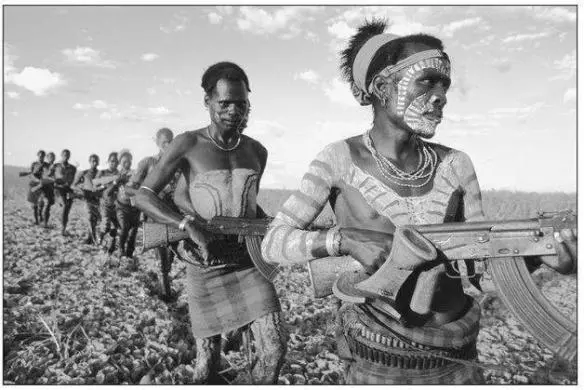

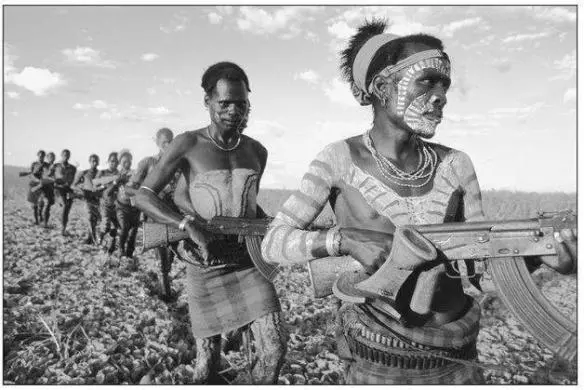

In pastoral areas, traditional people such as the Karamajong in Uganda had always fought other groups using spears because of traditional and spiritual imperatives. Introduction of the AK, however, spewing hundreds of bullets a minute, turned their societies topsy-turvy. The weapon not only raised the level of destruction among warring groups but also ratcheted up hostilities against repressive governments with whom the tribesmen formerly held no advantage. On a tribal level, AKs immediately endowed power to warlords over the authority traditionally held by tribal elders. Age and wisdom no longer determined status; Kalashnikovs did.

The AK changed cultural patterns in ways that westerners could hardly fathom. It became a standard-exchange barter amount for cattle among the group. In 1998, an AK might be worth three or four cattle. If the gun was registered with the Ugandan government, it was considered more valuable and the investment could be recouped in a few years. It also could be used to increase a person’s herd through cattle rustling, which until the advent of the AK was a relatively small-scale activity.

The AK also began appearing as parts of dowries.

This day-to-day incorporation of the AK was far from unique. In South Africa, black youths considered buying an AK as a rite of manhood as well as a way to fight government-sponsored apartheid. The rifle became such a strong icon of antigovernment groups like the African National Congress (ANC) that the government demonized the weapon in the media, equating it with the Soviet Union and Communism and thus justifying its legitimate suppression of such groups. In this way, the government used the ANC’s interest in the AK to allege that it was supported by the Soviet Union and was not a homegrown, grassroots organization.

Many AKs in South Africa came from Mozambique in the early 1990s as that nation’s twenty-year civil war was winding down. (South Africa is the only sub-Saharan nation that produces its own AK version, the Vektor R4, which is actually a copy of the Israeli Galil, itself a modified AK.) In that country, AKs were so commonplace, so easy to get, that they were used as currency.

This was a far cry from the situation when Mozambique in 1974 won its independence from Portugal. When the colonial power left, it took most of its arms with it. However, this did not deter groups contending for power from increasing their small-arms caches. According to UN estimates, armies on both sides of the ensuing civil war—the Front for the Liberation of Mozambique (FRELIMO), which had initiated the armed campaign of independence against Portugal in 1964, and the Mozambique National Resistance (RENAMO)—never amounted to more than 92,000 people, so outside authorities were shocked when they looked at the number of weapons left over after fighting ended in 1993.

Introduction of the AK turned pastoral people’s societies upside down. It not only raised the level of destruction among warring groups, who usually fought with spears and swords for traditional and spiritual reasons, but also ratcheted up hostilities against repressive governments over whom they formerly held no advantage. Here, Hamer warriors in Ethiopia’s Omo Valley patrol Lake Chew Bahir for protection against the Boranas, their worst enemies. © Remi Benali/Corbis

One report had the Mozambican government handing out 1.5 million AKs to civilian self-defense groups. But a 1994 Interpol presentation noted that 1.5 million AKs came from the Soviet Union alone. UN reports pegged the number at between 5 and 10 million weapons.

The true number may never be known. Although the United Nations collected almost 170,000 AKs from uniformed troops, many more weapons were kept by private individuals or smuggled or sold to neighboring South Africa, which saw an unprecedented surge in AKs as evidenced by prices plummeting to as low as five to ten dollars in some instances.

As a cultural icon, the AK clearly left its mark on Mozambique. The country’s flag features an AK crossed with a hoe on a field of horizontal red, green, black, gold, and white stripes. Both images are superimposed on an open book. The flag symbolizes the country’s commitment to defense, labor, and education. Mozambique’s coat of arms also displays the AK, hoe, and book over a map of the country and is seen every day on paper money and coins.

In 1999, the country held a contest to change the flag, ostensibly to replace the AK with a more peaceful symbol. Jose Forjaz, a widely known Mozambican architect, won the design competition, but nothing further happened. A constitutional package that would change the flag and coat of arms, and provide a new national anthem along with some other amendments, has been stalled for years. It’s unclear when or if the flag will ever change.

Even if the AK image is deleted from the flag and emblem, it remains embedded in the country’s consciousness, not only through the estimated one million deaths it caused, but through children, many of them now grown, who were named for the gun. “When I met the Mozambique minister of defense, he presented me with his country’s national banner, which carries the image of a Kalashnikov gun,” said Mikhail Kalashnikov. “He told me that when all the Liberation [FRELIMO] soldiers went home to their villages, they named their sons Kalash.”

By the late 1980s, the Kalashnikov’s reputation had already spread like a virus throughout the Far East, Middle East, and Africa, leaving a path of destruction and human suffering. In the Western Hemisphere, Central and South America were not spared the AK’s wrath. This ten-dollar weapon of mass destruction had already penetrated Latin America, leaving millions dead and displaced and helping to foster the world’s most powerful and brutal drug cartels.

5

THE KALASHNIKOV CULTURE REACHES LATIN AMERICA

AMID THE COLLAPSED buildings of Nicaragua’s capital, Managua—many structures remain in ruins after a devastating earthquake in 1972—rises the city’s largest statue, an iron figure with his outstretched arm thrusting skyward, defiantly gripping an AK.

Читать дальше