For Josiah Ober and Adrienne Mayor

I have used Roman place names wherever possible, with the exception of such common names as Italy and Spain.

I have translated all ancient Greek and Latin quotations myself unless otherwise noted.

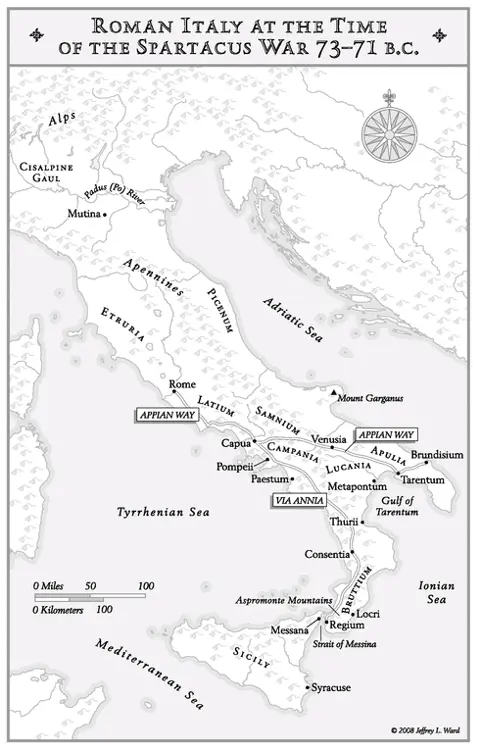

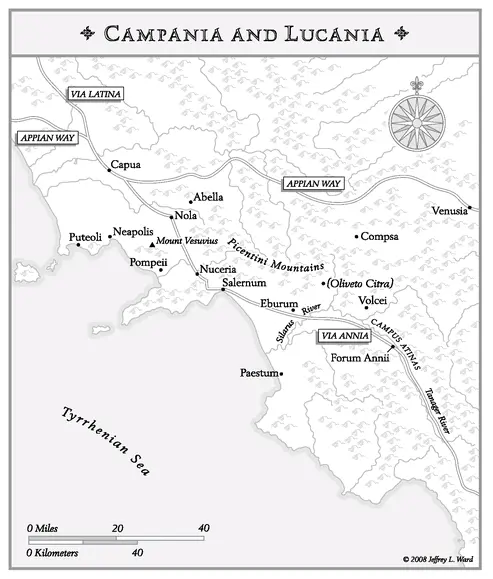

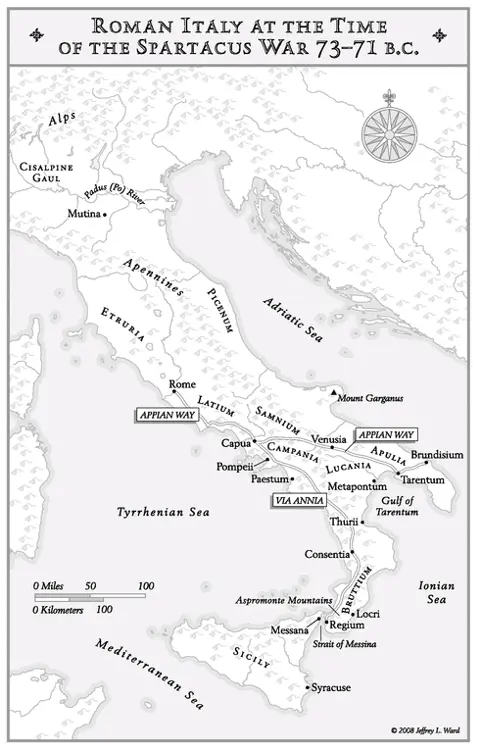

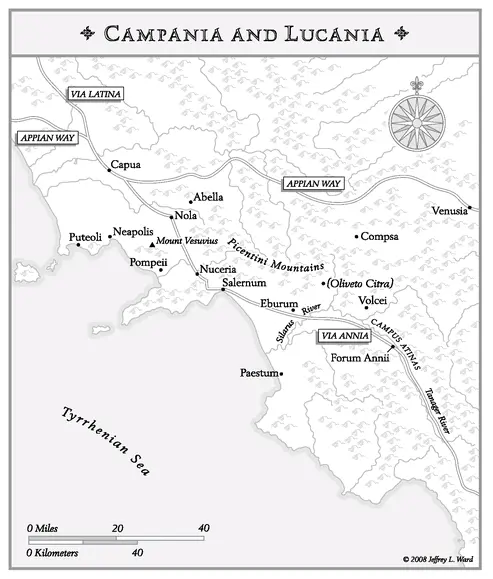

Lucius Cossinius was naked. Senator, commander and deputy to the general Publius Varinius, Cossinius usually wore a full suit of armour and a red cloak, fastened with a bronze brooch on his right shoulder. But now he was bathing. A bath was a luxury in wartime, but no doubt hard to resist after leading 2,000 men on the march. As he had approached, Cossinius could have seen the pool glistening in the grounds of a villa at Salinae - ‘Salt Works’ - located on a coastal lagoon near Pompeii. In the distance stood Vesuvius, still a sleeping volcano in those days, its hills green with pine and beech trees, its orchards overflowing with apples and with grapes that made wine good enough for a senator’s table; its soil teeming with hares, dormice and moles that the locals favoured as hors d’oeuvres.

While Cossinius let down his guard, the enemy prepared to strike. Runaway slaves, gladiators and barbarians, they were a rabble in arms, but they had already beaten Rome twice that summer. Their leader was as cunning as he was strong, as experienced as he was fresh, and he spoke words to steel the most timid soul. His name was Spartacus.

There was probably only a moment’s warning, maybe a centurion sounding the alarm or the shouts of the men. Cossinius, we might imagine, moved quickly out of the water and onto his horse before his slave finished rearranging his master’s cloak. Even so, Spartacus’s men burst into the grounds of the villa so fast that Cossinius barely escaped. Not so his supplies, which the enemy captured, and which would now go to feed the rebel force.

They hounded Cossinius and his men back to their camp. Most of the Romans were new recruits. Children of Italy’s abundance, they had nothing but hasty training to prepare them for a savage foe, some of them giants, red-haired and tattooed, and buoyed by success. In spite of the curses and threats of their centurions, some Romans ran away; the rest stayed and were slaughtered. Everything they had now belonged to the enemy, from their camp down to their arms and armour. Lucius Cossinius was naked again, but this time he was dead.

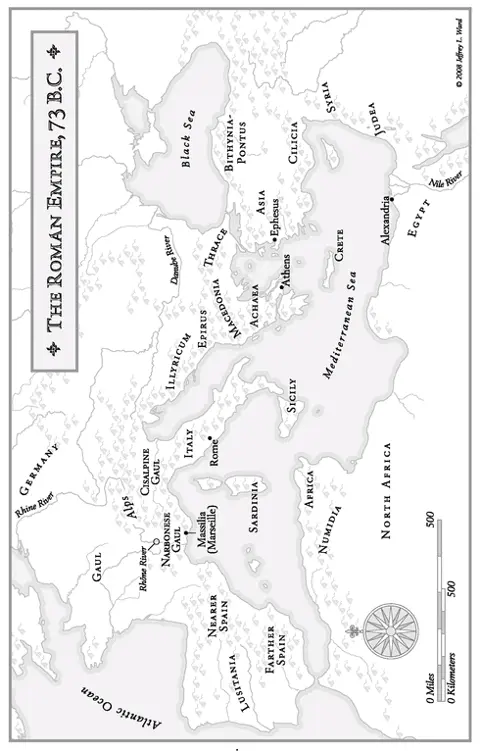

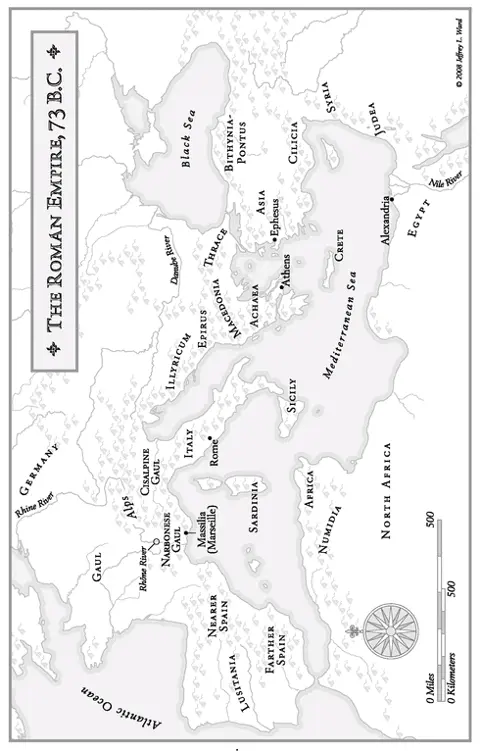

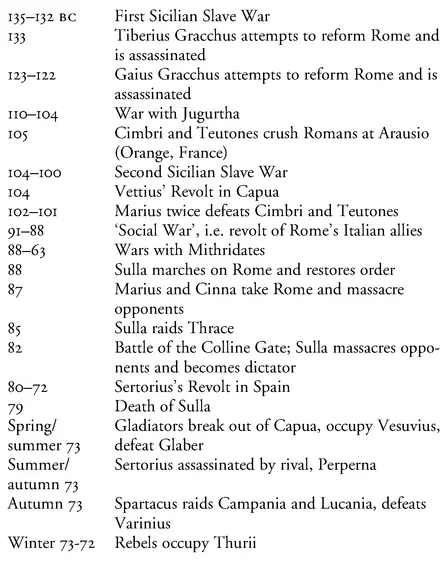

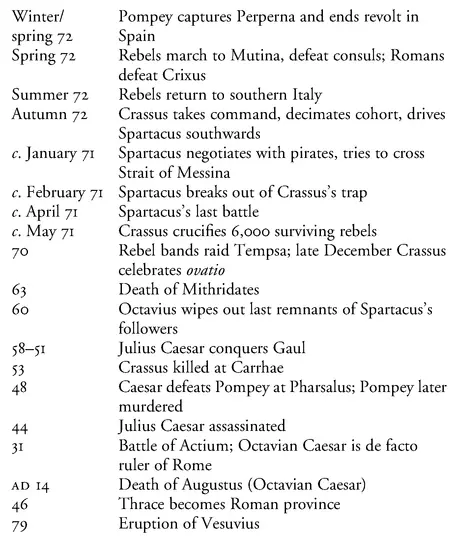

It was the autumn of 73 BC. After several months of rebellion, the fortunes of the Senate and people of Rome were heading towards a low ebb. A city that had shrugged off Etruscan adventurers, weathered a Gallic invasion, stood up to Hannibal’s charge, endured civil war, survived annual outbreaks of malaria, and fought its way to such power that it could think of itself as the head of the world, was afraid of a runaway gladiator.

What began as a prison breakout by seventy-four men armed only with cleavers and skewers had turned into a revolt by thousands. And it wasn’t over: a year later the force would number roughly 60,000 rebel troops. With an estimated 1-1.5 million slaves in Italy, the rebels amounted to around 4 per cent of the slave population. To put that figure in perspective, the USA in the nineteenth century had about 4 million slaves, and yet Nat Turner’s rebellion in 1831 involved only 200 of them.

Rome had seen slave rebellions before but this one was different. Earlier revolts had either been relatively small or, if extensive, far off in Sicily, but this enormous army had come within a week’s march of Rome. Not since Hannibal crossed the Alps had foreigners done so much damage to the Italian countryside. Earlier slave revolts coalesced around mystics and gang leaders, not gladiators and ex-Roman soldiers. Spartacus struck a chord in the Roman psyche. No other leader of rebel slaves was so well remembered or so feared. As a gladiator, Spartacus belonged to a group of men who were licensed to kill - to kill each other, that is: Romans had a lurid fascination with the arena but rebel gladiators aroused first disgust and then dread.

Spartacus came from Thrace (roughly, Bulgaria), an area known to Romans for its fierce fighters and ecstatic religion, and for its alternation between alliance and rebellion. As a one-time allied soldier in Rome’s service, Spartacus should have been a Roman success story. Instead, he had become the enemy within. Thracians, Celts and Germans - barbarians all, in Roman eyes - made up most of his followers. Earlier slave rebels came from the citified Greek East; fairly or not, the Romans scorned their warrior prowess. But they dreaded a fight against barbarians.

Timing made matters worse. When Spartacus began his revolt, Rome faced major wars at both ends of its empire. Mithridates, a king in Asia Minor (today, Turkey), had sparked a substantial war against Rome in 88 BC that had spread to Greece and Thrace and was still going strong after fifteen years. Meanwhile, in Spain, the renegade Roman general Sertorius ran a breakaway government whose Roman leaders had the support of a native resistance movement. Finally, at the same time, off the coasts of Crete, the Roman navy struggled to catch pirates who were wrecking the sea lanes. We know that Rome eventually defeated all these challengers. But in 73 BC that outcome was not yet clear.

By exploiting propaganda masterfully Spartacus threatened to widen his base of support. He sounded themes that appealed not only to slaves but also to Italian nationalists and to supporters of Mithridates. Although his message probably attracted few free men to his banner in the end, it was enough to frighten Rome.

Spartacus’s was antiquity’s most famous slave revolt and arguably its largest. It was a revolt that absorbed southern Italy, caught Rome with its homeland virtually defenceless, led to nine defeats of Roman armies and kept antiquity’s greatest military power at bay for two years. How was it possible? Why did the rebels do so well for so long? Why did they fail in the end? And how could the world’s only superpower have let such a problem persist in its own back yard?

It’s a story that should have been in pictures, and, of course, it is. In 1960 Spartacus appeared, a Hollywood epic starring Kirk Douglas and directed by Stanley Kubrick. The film was a hit then and remains a classic. It was loosely based on a bestselling 1951 novel by Howard Fast, which he wrote after serving a jail term for contempt of Congress during the McCarthy era. An American Communist who eventually left the party, Fast was not the first Communist to admire Spartacus. Lenin, Stalin and Karl Marx himself saw Spartacus as the very model of the proletarian revolutionary. German Marxist revolutionaries of 1919 called their group the Spartacus League; their failed uprising grew legendary. Soviet composer Aram Khachaturian wrote a ballet about Spartacus that won him the Lenin Prize for 1959.

Читать дальше