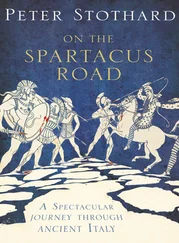

Ludus might mean ‘game’ but life there was serious. A new recruit took the most sacred oath imaginable - and the most terrible: he swore to be ‘burned’ (perhaps tattooed, tattoos being the mark of slavery), chained, beaten and killed with an iron weapon. It was, says the Roman writer Seneca, a promise to die ‘erect and invincible’ [19] Seneca, Letters 37.2.

, because facing death calmly was the height of the gladiatorial art. After his oath-taking, the new gladiator then followed a training schedule that was, in its own way, as pure and strict as a Spartan’s.

Being a gladiator was a special privilege in Roman eyes, and not merely because gladiators were treated better than the average slave. Not that the Romans were simply positive about gladiators. Instead, they considered gladiators to be both good and bad. To be forced to be a gladiator was demeaning; to volunteer as a gladiator was depraved; to become skilled as a gladiator was dangerous, but to die as a gladiator was sublime.

Gladiators didn’t have friends. They had allies, rivals, bosses, hangers-on, punks, spies, suppliers and double-crossers. The new gladiator learned whom to trust and whom to watch out for, who would cover his back and who would steal his food. He quickly took the measure of the men: the strong, the agile, the tough, the ruthless; the weak, the clumsy, the soft and the kind-hearted. A pecking order of leaders and followers would emerge, as brutal and as status-conscious as in any prison. One night a man shared a pre-combat meal with his comrades, the next day he killed his table-mate, and shortly afterwards arranged for the victim’s tombstone.

Maybe some gladiators deserted because life in the ludus was hard, but by Roman standards life there was not especially harsh. Discipline in the Roman legions, for instance, could be nearly as strict. Unlike gladiators, soldiers could not be tortured but they faced severe punishment for crimes ranging from theft and engaging in homosexual acts to loss of weapons and failure to keep the night watch. These punishments included whipping and execution by being clubbed to death.

Some of Vatia’s slaves might even have liked the discipline. They could hardly have minded the rewards. Victorious gladiators got glory, cash, celebrity and sex - which was better than what other slaves faced. And yet 200 gladiators decided to break out of Vatia’s ludus. If it was ironic that they, of all people, should spark a slave uprising, it was also typical. Throughout history, privileged slaves have often led revolts, maybe because they have high hopes. Did the gladiators explode because Vatia tightened the screws? Possibly; or perhaps theirs was a revolution of rising expectations.

Hollywood made one of Vatia’s trainers especially brutal, but we know next to nothing about Vatia and even less about his trainers. Even Vatia’s name is uncertain, since the sources call him either Lentulus Batiatus or Cnaeus Lentulus. According to a plausible theory, ‘Batiatus’ is a mistake; he was really Cnaeus Cornelius Lentulus Vatia, a Roman citizen from a rich and noble family known to have owned gladiators in Capua. The man was crude and thick-skinned enough not to mind having a job description - gladiatorial school owner (lanista, in Latin) - that Romans compared to butcher (lanius) or pimp (leno). Perhaps he kept his distance and left the management of the ludus to others, while he stayed in Rome. Maybe he never even met Spartacus before the revolt; who knows?

According to one ancient author, the gladiators decided ‘to run a risk for freedom instead of being on display for spectators’ [20] Appian, Civil Wars 1.116.539.

. It was humiliating to have to fight to the death for the entertainment of the Roman public. A certain greatness of soul runs through the whole story of Spartacus, from Capua to his last battle. One ancient writer says that Spartacus was ‘more thoughtful and more dignified than his circumstances, more Greek than his race’ [21] Plutarch, Crassus 8.3. For the translation of the Greek word prâotês as ‘dignified’, see Hubert Martin, Jr, ‘The Concept of Prâotês in Plutarch’s Lives’, Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies 3 (1960): 65-73.

. Another says that Spartacus had the support of an elite few men of prudence [22] Sallust, Histories frg. 98A.

and a free soul - in a word, of the nobles.

There is a chance that Spartacus himself had been born an aristocrat. Straws in the wind: the name Spartacus is found in a Thracian royal family; the ancient sources say that there were a few ‘nobles’ among the insurgents [23] Sallust, Histories frg. 98A.

, which probably means slaves of noble birth or descent; two contemporary Roman writers admired Spartacus, which would have been easier for them if he were patrician. Even among gladiators, the glamour of a noble name might have helped Spartacus to draw in supporters.

As Spartacus and his allies gathered support for the revolt, they might have spoken of profit and vengeance as well as freedom and honour. They might also have pointed out that the time was ripe. They might have noted that Mithridates was still carrying the torch of Roman resistance high in the East and that Sertorius’s revolt still smouldered in the West. And perhaps they knew of some of the many earlier slave rebellions against Rome: a dozen uprisings in Italy during the second century BC, two massive uprisings in Sicily (135-132 BC, 104-100 BC), and an anti-Roman coalition of slaves and free people in western Asia Minor between 132 and 129 BC. When in 88 BC Mithridates sponsored a massacre of Romans and Italians in western Asia Minor, he offered freedom to any slave who would kill or inform on his master. With so much revolt in the air, only a hermit could have remained ignorant.

Only thirty years before, Capua’s slaves had risen in revolt - twice. Old-timers in town might still have talked about it. In or around the year 104 BC, 200 slaves at Capua rebelled and were quickly suppressed; no other details survive. Another Capuan revolt in 104 BC was more serious. T. Minucius Vettius, a rich, young Roman, in love with a slave girl but buried under debt, rose in revolt from his father’s estate outside Capua. He formed an army of 3,500 slaves, armed and organized in centuries like a Roman legion. The Roman Senate took this threat seriously. They appointed Lucius Licinius Lucullus to restore order; he was a praetor, a high-ranking public official who was a combination of chief justice and lieutenant general. Lucullus raised an army of 4,000 infantry and 400 cavalry but he beat Vettius by cunning, not brute force. Lucullus offered immunity to Vettius’s general Apollonius (the name suggests a slave or freedman), who turned traitor. The result was mass suicide by the rebels, including Vettius.

The uprising failed but it left encouraging lessons to insurgents. Slaves could form an army, and one that was well organized and well armed. Rome was sufficiently impressed that it used treachery instead of attacking the rebels head-on. It was striking too that Roman forces barely outnumbered the slaves. Maybe Rome didn’t send more troops because it couldn’t send more troops. In 104 BC the Roman army was otherwise engaged.

The year before, in 105 BC, an army of migrating Germans and their Celtic allies had humiliated the legions at the Battle of Arausio (Orange) in southern France and killed tens of thousands of Roman soldiers. Not until 101 BC were the migrating Germans and Celts finally defeated. The two revolts in Capua c. 104 BC, therefore, challenged a regime that already had enough trouble.

Now, in 73 BC, the legions were abroad fighting Sertorius and Mithridates. At home a police force was all but non-existent. Maybe a new uprising could succeed where the old one failed. Opportunity beckoned but something more basic may have inspired rebellion: survival instinct.

Читать дальше