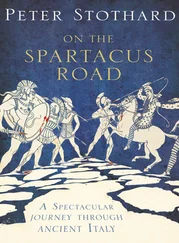

It was an unlikely school of revolution. Yet fights like this steeled the blood of the men who would start the ancient world’s most savage slave revolt.

Let us go back to where it all began, to the place where Spartacus lived and trained, the gladiatorial barracks owned by Cnaeus Cornelius Lentulus Vatia. Vatia was a lanista, an entrepreneur who bought and trained gladiators, whom he then hired out to the producers of gladiatorial games. Vatia’s business was located in the city of Capua [5] the ruins of ancient Capua are located in today’s city of Santa Maria Capua Vetere. The modern city called Capua was, in fact, ancient Casilinum.

, which sits about 15 miles north of Naples. It is a part of Italy renowned for its climate, but Spartacus was not likely to appreciate the 300 days of sunshine a year.

He had come to Capua from Rome, probably on foot, certainly in chains, likely tied to the men next to him. In Rome he had been sold into slavery to Vatia. Imagine a scene like that of the slave sale carved on a Capuan tombstone [6] the stele of Publilius Satyr, published by Theodor Mommsen et al., Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum, 17 vols. (Berlin: 1863-1986), vol. X.8222. For a photo, see http://www.culturacampania.rai.it/site/engb/Cultural_Heritage/Museums/Scheda/Main_works/works/capua_museo_campano_stele_di_publilius_satyr_.html?UrlScheda=capua_museo_provinciale_campano.

of the first century BC, possibly marking a slave trader’s grave. The slave stands on a pedestal, most likely a wooden auction block, naked except for a loincloth - standard practice in Roman slave markets. It was also standard to mark the slave by chalking his feet. Bearded and broad-shouldered, with his long arms at his sides, the slave in the relief looks fit for hard labour. And the artist uses a size imbalance to suggest a power imbalance, because he makes the slave smaller than the freedmen on either side of him.

Spartacus’s first view of Capua might have been neither its walls nor temples but its amphitheatre. The building rose up outside the city walls and just to the north-west of them, beside the Appian Way. The structure had the squat and rugged shape of one of Italy’s first stone amphitheatres, built in the Late Republic.

Most of Spartacus’s life had unfolded on the broad plains and winding hills of the Balkans but now his frame of reference was no wider than the walls of Vatia’s establishment, with occasional glimpses of Capua. The city and the business had much in common. Neither was respectable in Rome’s eyes and both depended on slave labour. Each occasionally offered a ladder of mobility to slaves. But there was one difference: outside the house of Vatia, the ladder sometimes led to freedom, but inside, it usually led to death.

Spartacus had taken the long route to Capua. In his native Thrace, young Spartacus had served in an allied unit [7] Florus, Epitome 2.8.7.

of the Roman army. The Romans called these units auxilia (literally, ‘the help’) and its men were called auxiliaries. These units were separate from the legions, which were restricted to Roman citizens. Although they were not legionaries, auxiliaries got a glimpse of Roman military discipline. Spartacus’s later military success against Rome becomes easier to understand if he had seen first-hand how the Roman army worked.

As an auxiliary, Spartacus was probably a representative of a conquered people fulfilling their military service to Rome; that is, he was probably more draftee than mercenary. As a rebel he would display the eye of command, which might suggest that he was an officer under the Romans. In all likelihood, he was a cavalryman.

Almost all of Rome’s cavalry were auxiliaries. None made fiercer horsemen than the Thracians. The Second Book of Maccabees [8] 12.35.

(included in some versions of the Bible) offers a powerful image of a Thracian on horseback: a mercenary, bearing down on a very strong Jewish cavalryman named Dositheus and chopping off his arm. The unnamed Thracian had thereby saved his commander, Gorgias, whom Dositheus had grabbed by the cloak. That happened in 163 BC. In 130 BC a Thracian cavalryman decapitated a Roman general with a single blow of his sword. Fifty years later the Romans still shivered at the thought.

According to one writer, Spartacus next deserted and became what the Romans called a latro [9] Florus, Epitome 2.8.8.

. The word means ‘thief’, ‘bandit’, or ‘highwayman’ but it also means ‘guerrilla soldier’ or ‘insur gent’: the Romans used the same word for all those concepts. We can only guess at Spartacus’s motives. Perhaps, like many Thracians, he had decided to join Mithridates’ war against Rome; perhaps he had a private grievance; perhaps he had taken to a life of crime. Nor do we know where he deserted, whether in Thrace, Macedonia or even Italy. In any case, after his time as a latro, Spartacus was captured, enslaved and condemned to be a gladiator.

In principle, Rome reserved the status of gladiator for only the most serious of criminals. Whatever Spartacus had done, by Roman standards it did not merit such severe punishment. He was innocent, as we learn from no less a source than Varro [10] Sosipater Charisius 1.133 (ed. Keil).

, a Roman writer in the prime of his life at the time of the gladiators’ war. Knowing that he was guiltless would have added flames to the fire of Spartacus’s rebellion. In any case, Spartacus had become the property of Vatia. The next and possibly last act of the Thracian’s life was about to begin.

Capua was known for its roses, its slaughterhouses and its gladiators. It was fat, rich and a political eunuch. In 216 BC, during the wars with Carthage, Capua had betrayed its ally Rome for Hannibal, Carthage’s greatest general. After the Romans reconquered Capua in 211 BC they punished the town by stripping it of self-government and putting it under a Roman governor.

Yet Capua had bounced back, richer than ever. The city was a centre of metalworks and of textiles. It was also the perfume and medicine capital of Italy as well as a grain-producer and Rome’s meat market, providing pork and lamb for the capital. Capua sits at the foot of a spur of the Apennines, Italy’s rugged and mountainous spine. To the south lies a flat plain, hot and steamy in the summer when the fields are brown, alternately rainy and bright in the winter when the fields are green. Some of the most fertile land in Europe, this was Campania Felix, ‘Lucky Campania’.

Lucky, that is, except from the point of view of its workers. Capua was in large part a city of slaves, both home-grown and imported. The number of slaves made Capua differ only in degree, not kind, from the rest of Italy. The 125 years of Roman expansion after 200 BC had flooded Italy with unfree labour. By Spartacus’s day, there were an estimated 1-1.5 million slaves on the peninsula, perhaps about 20 per cent of the people of Italy.

It was the heyday of exploitation in the ancient world, the zenith of misery and the nadir of freedom. Yet it was also an era of large concentrations of slaves, many of them born free, some of them ex-soldiers; of absentee masters, and of few or no police forces. Add to that the freedom given to some slaves to travel and even carry arms. Finally, consider the many possible refuges provided by nearby mountains. It is no accident that, within the space of sixty years, Sicily and southern Italy would explode into three of history’s greatest slave uprisings: first in two separate revolts on the island (135-132 BC, 104-100 BC) and then in Spartacus’s rebellion.

In the countryside, masses of slaves worked on farms, often in chains, usually locked up for the night in prison-like barracks. Others, employed as herdsmen, were left to fend for themselves or starve. Meanwhile, in town, slaves worked in every profession, from the shop to the school to the kitchen. In Capua, there were even slaves to collect the 5 per cent tax owed when slaves earned their freedom. A lucky few made it to freedom and some prospered; some, astonishingly, went into the slave business, turning their back on their humble origins. One Capuan freedman, for example, did not mind getting rich by manufacturing the rough woollen cloaks that were issued to slave field hands - issued once every other year, that is.

Читать дальше