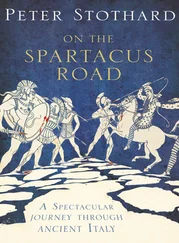

Varinius, Publius Praetor in 73 BC, Varinius suffered several defeats against Spartacus including one in which he lost his horse and nearly his life.

Vatia, Cnaeus Cornelius Lentulus The likely name for the man who is also called Batiatus, the gladiatorial entrepreneur who owned Spartacus at the time of his revolt.

Verres, Gaius (d. 43 BC) Rendered infamous by Cicero for his corruption as governor of Sicily, Verres probably did a good job of protecting the island from Spartacus.

What follows is a description of the main works used to write this study and a guide to further reading. It is not a complete list of references but a representative sample, with the emphasis on English-language scholarship. I include a few works in foreign languages that I have found essential, but many fine studies in French, German and Italian have been omitted.

The indispensable reference book for classics and ancient history is The Oxford Classical Dictionary, 3rd edn (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999). Excellent maps of the ancient world can be found in Richard J.A. Talbert, ed., The Barrington Atlas of the Ancient Greco-Roman World (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000).

The best place to begin is with Brent D. Shaw’s excellent edited collection and translation of the main documents of the revolt, Spartacus and the Slave Wars, a Brief History with Documents (Boston, Mass: Bedford/St Martins, 2001). The book also includes the main documents on the two Sicilian slave revolts as well as other Roman slave uprisings; it has a fine introductory essay too. Theresa Urbainczyk’s Spartacus (London: Bristol Classical Press, 2004) offers a concise and prudent overview. M.J. Trow’s Spartacus: The Myth and the Man (Stroud, UK: Sutton Publishing, 2006) is a highly readable work by a non-scholar. Keith Bradley’s Slavery and Rebellion in the Roman World, 140 B.C. - 70 B.C. (Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1989) has an outstanding chapter on Spartacus. F.A. Ridley, Spartacus, the Leader of the Roman Slaves (Ashford, England: F. Maitland, 1963), is a concise and often accurate little book by a socialist activist and writer. Several important books on Spartacus have appeared in European languages; two of the best are J.-P. Brisson, Spartacus (Paris: Le club français du livre, 1959) and A. Guarino, Spartaco (Napoli: Liguori, 1979). Guarino sees Spartacus as more bandit than hero; the argument does not convince but it is highly stimulating. The standard scholarly encyclopedia article is (in German) F. Muenzer, ‘Spartacus’, in August Pauly, Georg Wis sowa et al., Paulys Real-encyclopädie der classischen Altertumswissenschaft, 83 vols. (Stuttgart: 1893-1978), Vol. III A: cols. 1527-36 and Suppl. Vol. V: col. 993. There is a great deal of value, especially on topography, in the works of Luigi Pareti, particularly his Storia di Roma e del Mondo Romano III: Dai prodromi della III Guerra Macedonica al ‘primo triumvirato’ (170-59 av. Cr.) (Turin: Unione Tipografico-Editrice Torinese, 1953), 687-708, and Luigi Pareti, with Angelo Russi, Storia della regione lucano-bruzzia nell’ anti chita‘ (Rome: Edizioni di storia e letteratura, 1997), 459-69.

A 1977 scholarly symposium held in Bulgaria contains many important essays, most in English: Chr. M. Danov and Al. Fol, eds., SPARTACUS Symposium Rebus Spartaci Gestis Dedicatum 2050 A.: Blagoevgrad, 20-24.1X.1977 (Sofia, Bulgaria: Editions de l’Académie Bulgare des Sciences, 1981). Also in 1977 the Japanese Spartacus scholar Masaoki Doi published in English a valuable bibliography of scholarship on Spartacus, but copies are not easy to find: Bibliography of Spartacus’ Uprising, 1726-1976 (Tokyo: [s.n.], 1977).

The ancient evidence for Spartacus is notoriously inadequate. All the Greek and Latin sources are collected in one place, in the original languages, in Giulia Stampacchia, La Tradizione della Guerra di Spartaco di Sallusto a Orosio (Pisa: Giardini, 1976), which also offers (in Italian) a careful and measured study of the narrative of the revolt as seen through the various sources. The most important ancient work about Spartacus was probably the Histories of Gaius Sallustius Crispus, better known as Sallust (86- 35 BC). A failed politician who commanded a legion for Julius Caesar, Sallust was a teenager at the time of the Spartacus War. He wrote extensively about Spartacus in his Histories, and, to judge from what remains of this work, he wrote trenchantly, but only bits and pieces have survived. The basic Latin edition is B. Maurenbrecher, C. Sallusti Crispi Historiarum Reliquae. Vol. II: Fragmenta (Leipzig: Teubner, 1893). For an excellent translation and historical commentary of the surviving fragments of Sallust’s Histories, see Patrick McGushin, Sallust, The Histories. Translated with Introduction and Commentary, 2 vols. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992-4).

The great Roman historian Titus Livius, or Livy (59 BC - AD 12) also wrote about Spartacus, but that section of his work survives only in a sketchy summary probably written centuries later.

The two most complete histories of Spartacus’s revolt to survive from antiquity are by Plutarch (c. AD 40s-120s) and Appian (c. AD 90s-160s). They are useful but problematic. Both writers were Greek, and both moved in government circles in the heyday of the Roman Peace. Both wrote about Rome’s past, drawing their information from earlier writings that no longer survive, and each preserved important details. But Appian condensed his sources imperfectly, and Plutarch cared less about history than biography. His account of Spartacus, for example, is just a section of his biography of Spartacus’s conqueror, Marcus Licinius Crassus. Plutarch has a maddening habit of sacrificing narrative for a good moral. And Plutarch is our best single source about Spartacus! Still, Plutarch was careful and worldly, and a cautious reader can get a lot from him. There is an important historical commentary in Italian in M.G. Bertinelli Angeli et al., Le Vite di Nicia e di Crasso (Verona: Fondazione Lorenzo Vallo: A. Mondadori, 1993). An excellent historical commentary on Appian can be found in Emilio Gabba, Appiani. Bellorum Civilium Liber Primus (Firenze: La Nuova Italia Editrice, 1958).

Other Romans and Greek writers provide important details about Spartacus, all drawn, more or less accurately, from earlier histories. The most important of them are Velleius Paterculus (c.20 BC - AD 30s?), Frontinus (c. AD 30-104), Florus (c. AD 100- 150) and Orosius (c. AD 380s-420s). An important study of Florus on Spartacus is H.T. Wallinga, ‘Bellum Spartacium: Florus’ Text and Spartacus’s Objective’, Athenaeum 80 (1992): 25-43. Cicero lived through Spartacus’s revolt as a grown man and referred to it in several of his speeches, most notably in his orations against Verres, especially Oration 6 (also known as II,5). An English translation of the speech by Michael Grant is conveniently found in Cicero, On Government (Hardmondsworth, England: Penguin, 1994), 13-105. For an overview, see M. Doi, ‘Spartacus’ Uprising in Cicero’s Works’, Index 17(1989): 191-203.

Two brilliant but speculative and ultimately unconvincing studies argue that Spartacus’s revolt was primarily nationalist and anti-Roman rather than a slave revolt: W.Z. Rubinsohn, ‘Was the Bellum Spartacium a Servile Insurrection?’, Rivista di Filologia 99 (1971): 290-99, and Pierre Piccinin, ‘Les Italiens dans le “Bellum Spartacium” ’, Historia 53.2 (2004): 173-99. See also Piccinin, ‘À propos de deux passages des œuvres de Salluste et Plutarque’, Historia 51.3 (2002): 383-4 and Piccinin, ‘Le dionysisme dans le Bellum Spartacium’, Parola del Passato 56.319 (2001): 272-96.

The following are important studies of specific topics in the history of Spartacus’s revolt: R. Kamienik, ‘Die Zahlenangaben ueber des Spartakus-Aufstand und ihre Glaubwuerdigkeit’, Alter tum 16 (1970): 96-105, on the number of rebels at various points in the revolt; K. Ziegler, ‘Die Herkunft des Spartacus’, Hermes 83 (1955): 248-50, on the possibility that Spartacus was a Maedus; M. Doi, ‘Spartacus’ Uprising and Ancient Thracia, II’, Dritter Internationaler Thrakologischer Kongress vol. 2 (Sofia: Staatlicher Verlag Swjat, 1984): 203-7, and M. Doi, ‘The Origins of Spartacus and the Anti-Roman Struggle in Thracia’, Index 20 ( 1992): 31-40, on the influence of Spartacus’s Thracian background; G. Stampacchia, ‘La rivolta di Spartaco come rivolta contadina’, Index 9 (1980): 99-111, on the rural character of Spartacus’s supporters; C. Pellegrino, Ghosts of Vesuvius: A New Look at the Last Days of Pompeii, How Towers Fall, and Other Strange Connections (New York: W. Morrow, 2004), 147-66, on Spartacus’s sojourn on Mount Vesuvius; E. Maróti, ‘De suppliciis. Zur Frage der sizili anischen Zusammenhange des Spartacus-Aufstandes’, Acta Antiquae Hungariae 9 (1961): 41-70, on Spartacus’s planned crossing to Sicily; Maria Capozza, ‘Spartaco e il sacrificio del cavallo (Plut. Crass. 11, 8-9)’, Critica Storica 2 (1963): 251-93, on Spartacus’s sacrifice of a horse during his last battle. Allen Mason Ward, Marcus Crassus and the Late Roman Republic (Columbia and London: University of Missouri Press, 1977), esp. 83-98, ‘Chapter IV: The War with Spartacus’, offers a fundamental study of the crucial last six months of the war.

Читать дальше