Of the three Roman generals who closed in on Spartacus in 71 BC, only Marcus Lucullus died of natural causes. Lucullus celebrated a triumph for his success in Thrace, but the rest of his public life was not easy. His older brother, Lucius Lucullus, won great military success against Mithridates but made important enemies in Roman politics who forced him out of power. They made trouble at Rome for both brothers over the next decade. Lucius went insane and died around 56 BC. His grieving brother Marcus buried him on the family estate in the countryside near Rome and then died shortly afterwards.

After the frustration of serving under Gellius in 72 BC, Cato the Younger went on to greatness and tragedy. He became the Late Republic’s leading member of the old guard; no one defended the Senate’s privileges more stubbornly. Although Cato distrusted Pompey, he detested Caesar, so Cato fought for Pompey in the civil war that broke out in 49 BC. After serving in Sicily, Epirus and Asia Minor, in 46 BC Cato ended up in North Africa, where Caesar defeated Cato and pardoned him. Cato preferred suicide. Like Spartacus, his name became legendary. Cato lives on as an icon of Republican virtue.

Thracian rebels would continue to rise in arms against Rome for a century after Spartacus’s death. Big revolts broke out in 11 BC, AD 11 and 26, which forced Rome to send in the legions. Finally, in AD 46, Rome formally annexed Thrace, which had been a client state, as a province. Six years later, in AD 52, a Thracian from the tribe of the Bessi received Roman citizenship as a reward for loyal service in the Roman navy, where he had been a marine for twenty-six years. His name was Spartacus - or, rather, to use the variant spelling of his citizenship record, Sparticus. Sparticus assimilated, unlike the gladiator. Yet the great rebel, too, had once served Rome; if fate had taken a different turn, Spartacus might have headed towards Roman citizenship in 73 BC instead of rising in revolt. But Rome was a much more open society in AD 52 than it had been 125 years earlier.

It is in the shadow of Vesuvius that our story ends. In AD 14 an old man lay dying just west of Vesuvius, at the foot of the mountain or perhaps on its slopes: in either case, within the territory of the Italian city of Nola. He called for a mirror [257] the details come from Suetonius, Deified Augustus 98.5-100.1.

, had his hair combed and his sagging jaws set. Surrounded by his friends, he asked wittily whether he had played his part well in the comedy of life. He displayed coolness in the face of death that a gladiator would have envied. But he was no gladiator: he was the first man in Rome, the ‘father of his country’, as the Senate called him. Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus, better known as Augustus, Rome’s first emperor. As Augustus made his exit, Spartacus took a bow with him.

Nola lies at the foot of Mount Vesuvius. When Spartacus and his men poured down from the summit in 73 BC, they victimized the territory of Nola. As he lay dying, the man who ruled the world is unlikely to have turned his attention to local history. But in truth, Augustus had reason to look up towards the summit and think of the slaves who had once ruled the mountain. Without them, he might never have become emperor.

As a young man, Augustus held the honorary title of Thurinus, ‘the man from Thurii’. The sources disagree as to the origin of that title, but the likeliest explanation is a souvenir from his father. Augustus’s father was Gaius Octavius, the man who had cleaned out the nests of Spartacus’s remaining followers around Thurii in 60 BC. If Octavius senior had lived, he might well have gone on to other titles. As governor of Macedonia, he won a smashing victory over Thracian rebels; he was on his way back home to Rome in 58 BC to claim a triumph when he suffered an untimely death. His son was cheated of the bragging rights of having a pater triumphator, but he was entitled to call himself ‘Thurinus’. Not exactly military glory on the grand scale, but the label recalled Octavius’s finest hour.

For a young fatherless boy, being ‘Thurinus’ was a start. He would begin his career with an honour attached to his name. Ironically, his father’s marriage turned out to be even more helpful to his son than his military success, for Octavius had married Julius Caesar’s niece. Caesar would adopt the boy and young Thurinus grew up to become Octavian Caesar and then Augustus.

The shrewd Augustus might have considered, nonetheless, how much he owed Spartacus, at least indirectly. Spartacus’s rebellion had helped to make it possible for Augustus to end the Republic and become emperor. As scholars have pointed out, Spartacus had more symbolic than actual importance in the history of the later Roman Republic. Yet symbols matter. If Romans clamoured for order, if they willingly submitted to dictatorship, it was in small part the result of Spartacus’s symbolic power.

Arrius, Quintus. As propraetor in 72 BC Arrius served on the staff of the consul Gellius.

Batiatus - see Vatia

Caesar, Gaius Julius (100-44 BC) The famous Roman statesman made a veiled reference to Spartacus’s revolt in his Gallic War.

Cannicus (also known as Gannicus) Celtic co-commander of a breakaway rebel army that was defeated by Crassus in Lucania in 71 BC.

Castus Celtic co-commander of a breakaway rebel army that was defeated by Crassus in Lucania in 71 BC.

Cato, Marcus Porcius, Cato the Younger (95-46 BC) Fought against Spartacus under the consul Gellius in 72 BC.

Cicero, Marcus Tullius (106-43 BC) Makes several references to Spartacus, especially in his orations against the former governor of Sicily, Verres.

Crassus, Marcus Licinius (d. 53 BC) Was the Roman general who, holding a special command, defeated Spartacus.

Crixus (d. 72 BC) Celtic gladiator and Spartacus’s colleague as leader of the revolt against Rome.

Gellius, Lucius (c. 136-50s BC) Consul in 72 BC, suffered the humiliating defeat in battle by Spartacus.

Glaber, Caius Claudius, praetor In 72 BC was defeated by Spartacus at Mount Vesuvius.

Heracleo Active in Sicily, this pirate humiliated Verres by sailing into Syracuse Harbour under his nose.

Lentulus, Gnaeus Cornelius Claudianus Consul in 72 BC, was defeated in battle by Spartacus.

Lucullus, Lucius Lucinius (118-56 BC) Prominent Roman statesman and victorious commander against Mithridates, 73-66 BC.

Lucullus, Marcus Consul in 73 BC, governor of Macedonia, victor over the Thracian Bessi, he was recalled to Italy to help defeat Spartacus.

Mithridates (120-63 BC) King of Pontus, he led a serious and long-lasting revolt against Rome with which Spartacus or at least some of his followers sympathized.

Mummius Officer under Crassus, he was defeated by Spartacus in 72 BC.

Octavius, Gaius Father of the emperor Augustus, he defeated the last of Spartacus’s followers in 60 BC.

Oenomaus Celtic gladiator and one of the original leaders of the revolt, he was killed early in the rebellion.

Pompey, or Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (106-48 BC) One of the two leading Roman statesmen of his generation. Pompey defeated Sertorius in Spain and was recalled to Italy to help defeat Spartacus.

Publipor ‘Publius’s boy’, he joined Spartacus’s rebellion and guided the slaves through Lucania.

Sertorius, Quintus (c. 126-73 BC) renegade Roman general and brilliant guerrilla soldier, he led a ten-year-long rebellion in Spain.

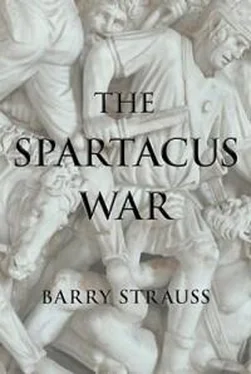

Spartacus (d. 71 BC) Thracian, Roman auxiliary soldier, bandit and gladiator, Spartacus led the most famous slave revolt of antiquity for two years in Italy, 73-71 BC.

Thracian Lady Spartacus’s female companion, whose name has not survived, was a prophetess of Dionysus who preached Spartacus’s mission.

Читать дальше