The high priests of morality in the Hays Office objected to We Accuse , reported Time , because “some of the atrocity shots are shown more than once, and the word ‘damned’ is used—attributed to the Germans in the line, ‘Let them (Russians) bury their dead and be damned’.”

The Hays Office gave Hitler a posthumous victory. In stifling We Accuse, it shoveled more dirt on the graves of the Russian dead, burying them and their stories even deeper, so that one day no one would remember or give a damn.

“Could it be we are all beneath great ruins and we’ll never crawl out?” Yevtushenko wrote in The Apple Trees of Drobitsky . “We are working our way out. An ignominious task, though enormous! Only don’t let the demolition shovel succeed again in finishing off those who are trying to crawl out.”

It’s left to us—the children and grandchildren of the survivors—to deny Hitler’s ghost, and to ensure that the greatest coverup in history does not succeed.

Kharkov under Nazi rule. Seventy percent of the city was destroyed during the Germans’ 22-month occupation.

Shell-shocked Hotel Krasnaya in Kharkov. Krasnaya is Russian for red—or beautiful.

Downtown Kharkov buildings that escaped massive damage during German bombing and shelling.

Dzerzhinsky Square in Kharkov during the war—five times larger than Red Square in Moscow—renamed Freedom Square after Ukraine declared independence.

Kharkov church ravaged by German attacks. Nazis targeted cultural, educational, and religious institutions no less than military installations in an attempt to eviscerate existing society in Kharkov.

Gosprom—government buildings circling Dzerzhinsky Square—were the first high-rise buildings in Ukraine constructed of ferro-concrete and survived sustained German attacks.

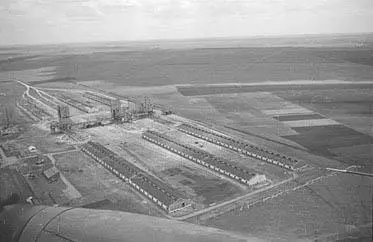

German reconnaisance photo of unnamed facility, possibly agricultural, near Kharkov.

Life goes in Nazi-occupied Kharkov.

Dispirited citizens in the Kharkov marketplace. An estimated 100,000 residents died of hunger during German occupation.

Portrait of Hitler in a Kharkov store window. In the first weeks of the war in western Ukraine, the Führer was hailed for liberating Ukraine from the tyranny of Stalin.

A German soldier directing “traffic” in central Kharkov.

Anti-Semitic Nazi propaganda in a Kharkov store window. Most Jews fled east to the Urals before the Nazis arrived. Those who stayed—some 16,000—were killed at Drobitsky Yar.

Boys inspect a German tank in downtown Kharkov.

Geman attacks devastated the infrastructure of Kharkov, destroying most bridges, the railway junction, power stations, telephone and telegraph connections, and fifty industrial plants.

Kharkov citizens exult at the hanging of four convicted war criminals—three Germans and a Russian traitor—on Dec. 19, 1943.

The crowd surges toward the gallows of fresh-cut wood erected on the grounds of a market burned down by the Nazis. Journalists estimated 40,000 to 50,000 onlookers.

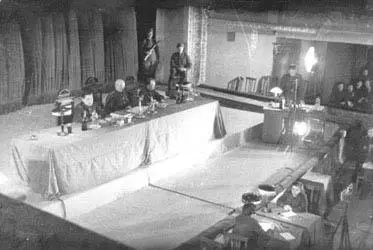

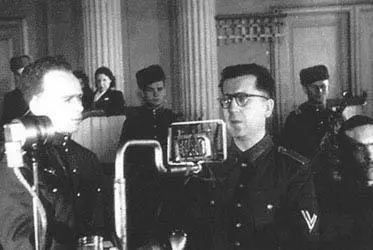

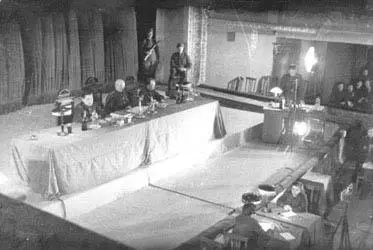

The makeshift courtroom in the Opera House, illuminated with klieg lights for the filming of movies and newsreels. Photo courtesy of Yad Vashem.

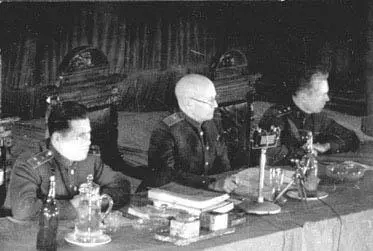

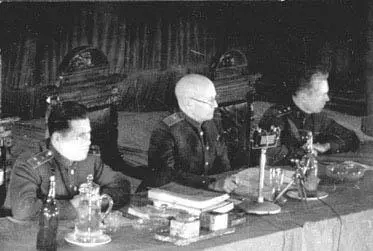

Military Tribunal of the 4th Ukrainian Front. Presiding judge (center), Major General Miasnikov. Photo courtesy of Yad Vashem.

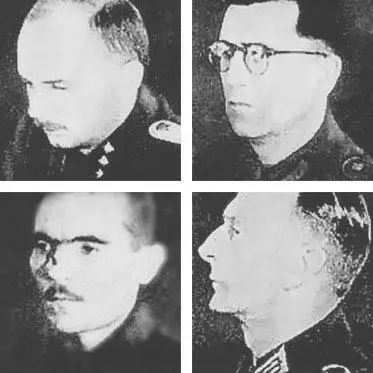

Defendants Bulanov, Ritz, Reinhard, Langheld in the courtroom. Captain Langheld was the only German to maintain his military bearing, even on the gallows. Photo courtesy of Yad Vashem .

SS Lt. Ritz standing before the court, perhaps pleading for mercy before the judges retire to decide the sentences. Photo courtesy of Yad Vashem.

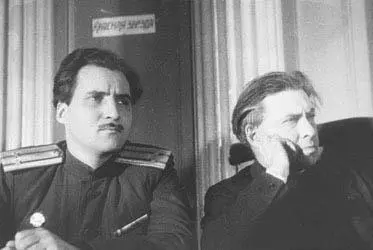

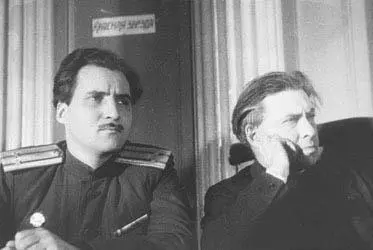

Russian writers Konstantin Simonov and Ilya Ehrenburg (co-editor with Vassily Grossman of The Black Book ) observing at the Kharkov trial. Photo courtesy of the U.S. Holocaust Museum.

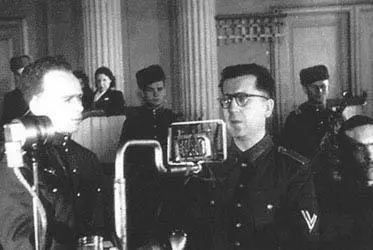

Reinhard Retzlaff, corporal in the German Secret Police, testifies at the trial. Photo courtesy of Yad Vashem.

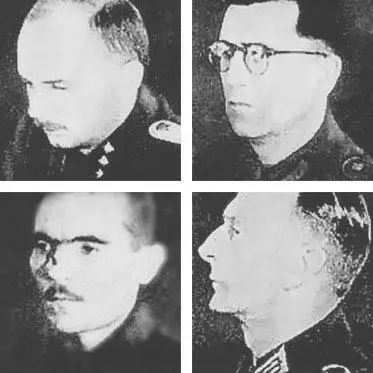

The defendants. Clockwise, starting at lower left: Mikhail Bulanov, Hans Ritz, Reinhard Retzlaff, William Langheld. Photos courtesy of Sovfoto .

Russian soldiers memorialized at Sokolniky Park outside Kharkov, which exchanged hands four times during the war.

Memorial at Drobitsky Yar near Kharkov where 16,000 Jews were murdered and buried in ravines by Germans.

Two of four tablets at Drobitsky Yar memorial engraved with the admonition “Thou Shalt Not Kill,” in myriad languages.

Markers at the site of the tractor factory on the outskirts of Kharkov that served as a temporary ghetto for Jews on the way to the killing field at Drobitsky Yar. Monument to left honors Righteous Gentiles who hid Jews from the Nazis.

Entrance pathway leading to the Motherland statue at Sokolinky Park near Kharkov.

Bus shelter with red-and-blue floral design. Sign in Russian reads: Drobitsky Yar.

Menorah at the end of the entrance road to Drobitsky Yar.

Dueling monuments at Drobitsky Yar killing field south of Kharkov. Obelisk to left, erected by Soviets in 1955, makes no mention of Jews. Monument to right, built in 1998, corrects the historical record.

Heroic statuary in Kharkov center.

Monument in Sokolniky Park where thousands of Jews and Russian soldiers were murdered.

Motherland statue, with beating electronic heart, at Sokolniky Park near Kharkov.

Babushka in balcony at Kharkov music conservatory, December 2010.

Site of the Kharkov synagogue where 400 elderly, crippled Jews and children were locked in by the Nazis and perished in December 1941.

Author at the Kharkov Holocaust Museum (2010) with founder Larisa Volovik (left) and daughter Yulana Volshonok, curator.

Plaque at the site of the old Opera House where the 1943 trial was held before an audience of local residents.

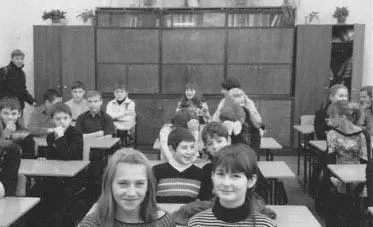

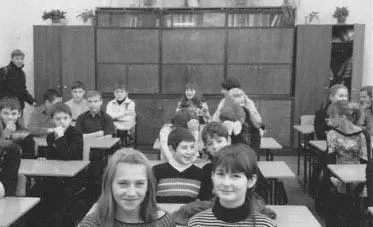

Students at School 13 where Zhanna attended at same age.

First and third generation survivors—Zhanna Dawson and granddaughter Aimee—at Timber Creek High School in Orlando, FL, January 2011. Photo by Wendy Doromal.

The Arshansky extended family, circa 1935 in Kharkov. Zhanna is second from left between father Dmitri and mother Sara. Both perished at Drobitsky Yar.

Читать дальше