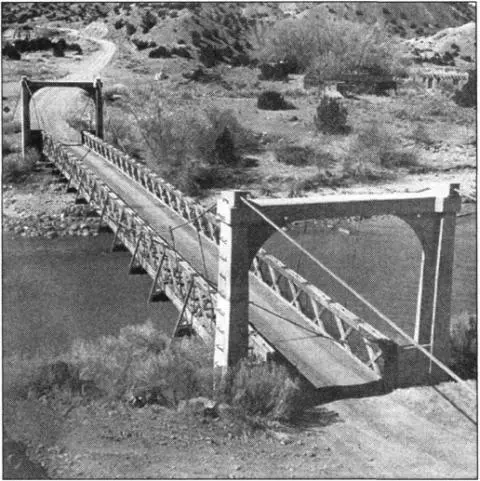

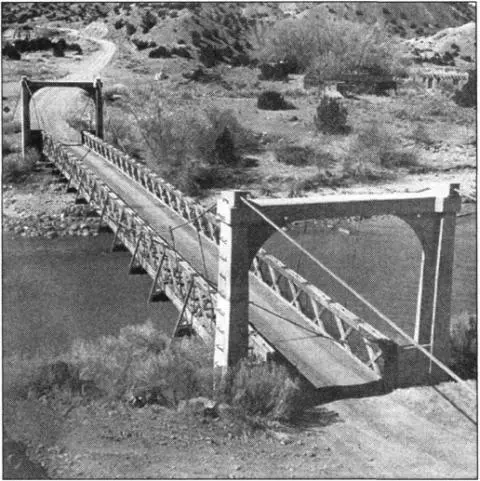

Otowi Bridge leading to Los Alamos, New Mexico

Robert Oppenheimer had not been Groves’s immediate choice as director of the new laboratory. He had first reviewed the more obvious candidates. Despite their initial prickly encounter, he already regarded Ernest Lawrence as an outstanding experimental physicist but did not believe Lawrence could be spared from the work on electromagnetic separation of U-235 at Berkeley. Arthur Compton was also highly competent but was at full stretch running the Met Lab at Chicago. The chemist Harold Urey at Columbia University, the discoverer of deuterium, was a possibility but, in Groves’s view, too weak a personality. Oppenheimer was, Groves concluded, the best man available.

Groves knew he was taking a considerable risk. As Hans Bethe recalled, “Oppenheimer had never directed anything—he was a pure theoretical physicist interested in the most advanced ideas—nobody trusted him except Groves.” However, Groves brushed aside the reservations and alternative suggestions of Arthur Compton and Ernest Lawrence, who argued that Oppenheimer lacked the experimental and administrative experience to run a laboratory, was not a Nobel Prize winner, and would find it hard to impose his authority. Oppenheimer’s sheer intellectual ability would, Groves believed, drive the project on. However, he promised Lawrence and Compton that, should Oppenheimer prove inadequate, they could take over.

Far more surprisingly, Groves ignored evidence of Oppenheimer’s left-wing sympathies and communist connections. His wife, Kitty, whom he had married in November 1940, was a former communist who had been married twice before. Her first husband was an American Communist Party member, killed fighting for the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War. She had then married an English doctor, who had moved to the United States with his new wife. Less than a year later, she and Oppenheimer had fallen in love, and within another year she had obtained a Nevada divorce. Oppenheimer himself had earlier been engaged to a Berkeley professor’s daughter, Jean Tatlock, a committed member of the Communist Party with whom he was still in touch.

Groves was an archconservative with an inherent distaste for liberal thinkers and an obsessive attitude toward security. He infiltrated counterintelligence officers among the workforce of the Manhattan Project. He even had himself tailed to see whether he was under enemy surveillance and carried a small automatic pistol in his trousers pocket when traveling. He ordered any failure of plant or machinery to be rigorously examined in case it was the product of sabotage. Yet he dismissed the assertions of U.S. military intelligence that Oppenheimer was “playing a key part in the attempts of the Soviet Union to secure, by espionage, highly secret information which is vital to the security of the United States.” After personally reviewing the evidence against Oppenheimer, he concluded that “his potential value outweighed any security risk.” He demanded that Oppenheimer be given security clearance, insisting, “He is absolutely essential to the project.” Nevertheless, as Groves well knew, Oppenheimer would remain under surveillance by military intelligence throughout. They tapped his phones and tailed his movements.

Groves also believed it essential to find a prime contracting agent for Los Alamos to function formally as employer of the staff and procurer of whatever was needed, and he appointed the University of California. Obtaining the right experimental equipment was one of the first challenges, but the project progressively begged, borrowed, and leased from universities across the United States, acquiring a cyclotron and several linear accelerators from Harvard and the Universities of Illinois and Wisconsin.

Oppenheimer meanwhile was identifying the team he wished to bring to Los Alamos. A potential difficulty was that Groves wanted to draft the laboratory’s scientists into the army, believing it would contribute to discipline and security. Oppenheimer initially supported him. According to Hans Bethe, “Oppenheimer was eager to do this—he would have been a lieutenant colonel.” However, others were much less certain, and they found a champion in the highly respected American physicist Isidor Rabi. Although Rabi did not plan to work at Los Alamos himself, believing that his present work on radar had more short-term importance for the war effort, Bethe recalled that he “came to us and said ‘don’t do that. If you make this a military laboratory nothing will ever, ever happen. You will need hundreds of permissions just to buy a screw of one diameter rather than another, and you’ll be commanded by Groves, who’ll boss you around. You won’t be able to refuse; you’ll have to do it because he is the general even if you know the experiments are pointless.’”

Oppenheimer and Groves agreed on a compromise. During the experimental stage of the project, the laboratory would remain under civil administration, but when large-scale testing began—and, whatever happened, not before 1 January 1944—scientists and engineers would become commissioned officers. In fact this never occurred. Groves wisely did not raise the militarization question again. He did, however, establish two lines of command at Los Alamos. Oppenheimer would be scientific director, but there would also be a military commander: Lieutenant Colonel John M. Harmon. [29] Harmon was replaced after four months because of a weakness for alcohol and difficulties in his relations with nonmilitary personnel. His successor was Lieutenant Colonel Whitney Ashbridge.

The site itself would be a military reservation, fenced and guarded. The technical facilities and laboratories would be housed within an inner protected zone—the “Technical Area.”

By April 1943 the new laboratory was beginning to function, although it was still, essentially, a building site. Some three thousand construction workers, billeted there since the previous December in cramped trailers, had made remarkable progress on a main building, five laboratories, a machine shop, a warehouse, and the first accommodation blocks. However, most of the buildings were not ready. The roads oozed with mud when it rained. When it was fine, building dust blew everywhere. To one new arrival the site looked “as raw as a new scar.” A few scientists moved into the old school buildings, but the rest lodged in dude ranches and were bused daily to Los Alamos along bumpy dirt roads, where surprised chickens ran for cover.

Oppenheimer organized a series of lectures to review the latest state of knowledge in atomic physics and to thrash out a detailed experimental program. As well as those already on the site, he invited others like Enrico Fermi and Hans Bethe whom he hoped to attract to Los Alamos or whose work elsewhere would contribute to the design and building of the bomb. Those in academic posts were paid the equivalent of their university salaries. Others were remunerated according to their qualifications. Oppenheimer’s own pay was $10,000 a year—a sum he considered excessive. His sustained attempts to have it lowered failed. The scientists discussed everything from how best to determine the detailed characteristics of chain reactions—including how rapidly new neutrons would be released in each fission—to how much fissionable material it would take to make a bomb. A fundamental question was whether to use U-235. or plutonium—or indeed both—as bomb fuel. As Groves and Oppenheimer knew, it would be some time before sizable amounts of either material became available from Oak Ridge and Hanford. In the meantime all investigations of the chemical properties of U-235. and plutonium would have to be carried out on microscopic samples, and it would be necessary to pursue both types of bomb in tandem.

Читать дальше