Life was certainly strange for the new arrivals as they adjusted to existence behind the wire. They could tell no one where they were; the only address they were allowed to quote was “Box 1663, Santa Fe.” The site itself was confusing. Barrack-like buildings stood at odd angles on streets without names, all alike and all painted green, camouflaged among the green pines. They were so uniform that it was easy to get lost. People used the cylindrical wooden water tower on the site’s highest point to orient themselves.

Rose Bethe was appointed head of the housing office and was hence responsible for allocating accommodations—a task, as another Los Alamos wife described, requiring every ounce of her “self-reliance, efficiency and stubbornness.” There were a few ground rules to help her. Childless couples were only entitled to a one-bedroom apartment; couples with one child were allocated two bedrooms; and couples with two children were given three-bedroom dwellings. There were, nevertheless, perpetual problems to solve and people to soothe. Edward Teller and his beloved, monumental piano were placed right below a quiet, contemplative bookworm who relished silence rather than Teller’s nocturnal sonatas. An enthusiastic chemist with a passion for conducting explosive experiments in his apartment lived adjacent to a large brood of children.

A childless couple asked Rose for a two-bedroom apartment. When she inquired whether they were expecting a baby, the blushing pair replied, “No, but we let nature take its course.” Babies were, in fact, a prominent feature of life at Los Alamos, which was, above all, a young site—the average age was twenty-seven. Many couples decided to start their families there. Medical care in the one-story hospital was free, and it was especially strong in pediatrics and gynecology. Groves later wrote wryly, “Apparently we provided adequate service, for one of the doctors told me later that the number and spacing of babies born to the scientific personnel surpassed all existing medical records.” Some of the scientists blamed Groves for a perennial shortage of diapers, which they believed he had arranged on purpose. They also believed he had ordered Oppenheimer to discourage people from reproducing, but Oppenheimer’s own daughter, Toni, was born at Los Alamos. Like the others, her place of birth was simply listed as Box 1663, Sandoval County Rural.

There were tensions between parents and dog owners. Many had brought their pets with them, and the animals roamed the mesa at will. One dog started biting people and was found to have rabies. Rules were hastily introduced to keep dogs under control, but, as a Los Alamos mother later recalled, “when the dog owners got tired of keeing their pets inside or on a leash, they suggested putting the children on leashes and letting the dogs go free.”

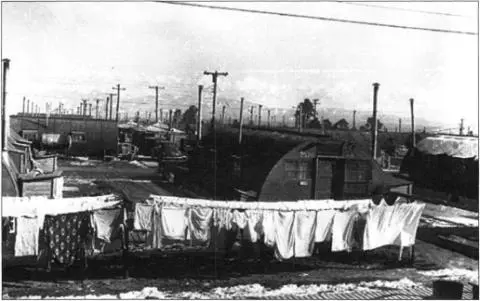

Living quarters at Los Alamos

The most desirable residences were in “Bathtub Row.” These attractive, sturdy stone-and-log cottages had belonged to the school. Their great attraction—hence the nickname—-was that they possessed baths, whereas the new army-built accommodations had only showers. At first, only the most senior people like Oppenheimer and his wife, who settled into the erstwhile headmaster’s house, lived there. But later, as others moved in, “it became uncertain in envious minds whether Bathtub Row derived its lustre from its residents or whether the residents acquired distinction from living in it,” according to one wife. Apartments in nearby “Snob Hollow” were also highly prized.

Snobbery was a genuine issue, as the American physicist Luis Alvarez discovered shortly after arriving at Los Alamos. As news spread that a family called Alvarez was moving in, other wives in the apartment building hurried to the housing office to complain about living next to Spanish-Americans. They were reassured to learn that the tall, blond Alvarez was only partly Spanish. The shortage of domestic help was another potential source of discord. Indian girls from the nearby villages were assigned by need rather than by the ability to pay. Kitty Oppenheimer, who had a full-time maid, took a role in the allocation. As an incentive to wives to work, those who did volunteer were given priority with household assistance.

Wives were not the only women working at Los Alamos. Promising young female scientists were recruited—like Joan Hinton, a graduate physics student from the University of Wisconsin, who worked on the design and construction of research facilities. By October 1944 there would be twenty women scientists and about fifty women technicians working on the site, in addition to nurses, teachers, secretaries, and clerks.

Frenetic partying became an established feature. As Emilio Segre recalled, “The isolation of Los Alamos pushed families to an active social life: there were many dinner parties; many people for the first time took up poker and square dancing.” Amateur dramatics flourished—Edward Teller played a corpse in a production of Arsenic and Old Lace. Oppenheimer also negotiated with a local woman, Edith Warner, who agreed to provide dinner three nights a week for small groups of scientists and their wives at her little house on the banks of the Rio Grande. As Oppenheimer had hoped, it gave them a brief respite from the stressful claustrophobia of the site.

The extraordinary surroundings, the ever-changing colors of mountains, sky, and desert, the clear, crisp air, the vivid flowers that bloomed from early spring to late autumn also helped invigorate people. The scientist Philip Morrison, summoned to Los Alamos, was seduced by “the utterly enchanting landscape.” To Robert Christy it was “a wonderful environment for anyone who liked the outdoors. The only ones who didn’t like it were the complete New Yorkers.” There were trails to ride and hike, streams to fish, Indian ruins to visit, and in the winter snowy slopes to ski. Leo Szilard, still in Chicago, had warned departing Met Lab colleagues that “nobody could think straight in a place like that. Everybody who goes there will go crazy,” but he would, for once, be proved wrong. Despite the pressures, many would remember their time at Los Alamos as the most stimulating and enjoyable of their lives.

• • •

Meanwhile rapid progress was being made at the two giant industrial sites of Oak Ridge and Hanford. At Oak Ridge, where construction was shared between several contractors, work began in early 1943 on Lawrence’s electromagnetic uranium-separation plant, code-named “Y-12.” It was based on cyclotrons modified into mass spectrographs that were known as “calutrons” after the University of California. They were put together in great “racetracks,” each containing ninety-six calutrons. Eventually, fifteen such racetracks would be built. From the outside the complex of concrete-and-brick buildings connected by a maze of streets with gantries of pipework and electrical wiring passing overhead resembled a conventional chemical plant.

In June the first ground was broken at Oak Ridge for the gaseous diffusion plant, code-named “K-2 c” and so immense that it would consume more electricity than a small city. At half a mile long, it was probably the largest chemical engineering plant ever built. In the interests of safety, Y-12 and K-25 were located in valleys seventeen miles apart. With no time to build pilot plants, the respective designs were based on Lawrence’s research at Berkeley and Harold Urey’s at Columbia. As Groves later wrote, “Research, development, construction and operation all had to be started and carried on simultaneously and without appreciable prior knowledge.”

Читать дальше