On the bitterly cold night of 19 November 1942, two four-engine RAF Halifax bombers, each towing a glider holding seventeen British commandos, took off for Norway’s remote Hardanger Plateau. On the plateau a team of four British-trained Norwegian commandos—code-named “Grouse”—listened carefully for the sound of approaching aircraft engines. The team, led by Jens Anton Poulsson, accompanied by radioman Knut Haugland, Claus Helberg, and Arne Kjelstrup, had parachuted in a month earlier. Several times Haugland thought he heard through the headphones of his radio direction-finding equipment the buzzing that would announce Freshman’s arrival. His comrades flashed signal lights into the sky, but no gliders floated silently in to land. Shortly before midnight, the Grouse team returned frustrated to their base-hut.

Radio messages from London soon told them that both gliders and one of the Halifaxes had crashed in sudden bad weather. The fate of the survivors would emerge only after the war. The glider that had been released by the surviving plane had crashed on a mountaintop near Stavanger, killing eight outright. The Germans quickly captured the nine survivors. They took four severely injured commandos first to the hospital and then to Gestapo headquarters for interrogation. Afterward, a German medical officer gave them a series of lethal injections. When they failed to die quickly enough, Gestapo men stamped on their throats. They then flung the four bodies into the sea. The five uninjured men were sent to Grini concentration camp north of Oslo. Two months later, in January 1943, the Germans tied the men’s hands behind their backs with barbed wire and shot them.

The other glider and its mother Halifax crashed soon after crossing the Norwegian coastline. All aboard the plane died instantly, but on the glider only three were dead. Of the remaining fourteen, three were badly injured but the rest were in reasonable shape. Two commandos struggled through the deep snow to a farmhouse to beg for help. The frightened farmer, knowing the Germans would shortly arrive, refused, sending them instead to the local sheriff, who at once phoned the German authorities. The Germans quickly captured the men and executed them all a few hours later.

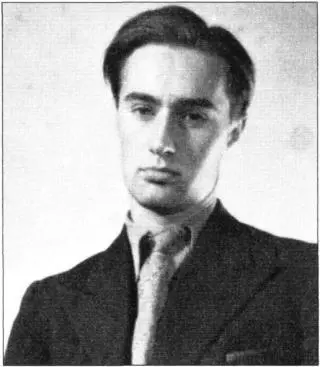

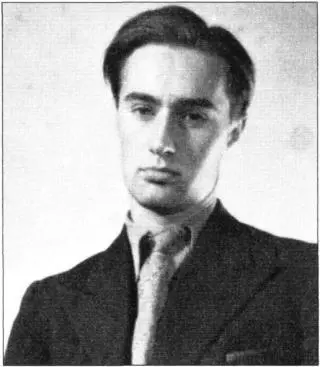

The total failure of Operation Freshman posed a stark dilemma to the British. Dare they hazard more men, especially now that the Germans had been alerted to British interest in the Rjukan area? Yet how could they allow German heavy water production to continue? They decided to try again, using Norwegian commandos familiar with the terrain, who would parachute in. The man selected to lead the new expedition—code-named “Gunnerside”—was Joachim Ronneberg, who had fled Norway after the German occupation. In early December 1942 he was training Norwegian resistance fighters at a Special Operations Executive (SOE) camp in the west of Scotland. He was ordered to pick five men to accompany him and to be ready in two weeks’ time. The twenty-three-year-old Ronneberg appointed as his second-in-command Knut Haukelid, who had plotted unsuccessfully to kidnap the Norwegian puppet prime minister Vidkun Quisling, before himself escaping to Britain. [28] Vidkun Quisling was the origin of the word quisling to describe a person collaborating with an enemy occupier.

Joachim Ronneberg

The team trained at a secret SOE school at Farm Hall, a country house near Cambridge, where, ironically, captured German nuclear scientists would one day be interned. Using microphotographs of blueprints of the Norsk-Hydro plant, smuggled out of Norway in fake toothpaste tubes, the British had reconstructed key parts of the plant, including wooden replicas of the eighteen cells that produced the heavy water. Unknown to the team, their training was being guided by Jomar Brun, the ingenious castor oil saboteur, also recently smuggled out of Norway on Churchill’s express orders.

Meanwhile, still in Norway, the Grouse team was surviving high in the mountains while awaiting fresh orders from London. The failure of Operation Freshman had been, as Poulsson wrote in his diary, “a hard blow.” Since then they had been pushed to their limits physically and emotionally, dodging German patrols, bivouacking in remote huts, and eating anything they could find—sometimes just “reindeer moss,” the soft, green moss beneath the snow on which reindeers grazed and so acid as to be barely digestible even when boiled into a soup. Some of the men became almost too weak to stand, and their skin turned yellow. Poulsson’s timely shooting of a reindeer on Christmas Eve probably saved them, providing protein and vitamins. They ate every part of the animal, including eyes, brains, and stomach. Even the reindeer moss, predigested in the animal’s stomach, proved more palatable than the fresh. A message from London of a new operation heartened them, only for them to be disappointed again when, in January 1943, the pilot of the plane bringing the Gunnerside men aborted the mission after failing to locate the drop site in the shadowy, moonlit maze of the snowy mountains.

On 16 February a fresh message announced that the Gunnerside commandos were coming. The plane again missed the drop point, but the men parachuted anyway, landing on the Hardanger Plateau with containers of arms and explosives and packs containing skis and sledges. They buried their equipment in the snow and found a hut to shelter them while they worked out what to do. A map in the hut showed they were some miles from the rendezvous point, but three days of vicious snowstorms kept them pinned down.

Finally, on 23 February, skiing over the frozen terrain in their white camouflage suits, they spied the tiny dot of a distant figure. Ronneberg ordered Haukelid to ski ahead and investigate. Drawing nearer, pistol at the ready, he saw not one man but two, both heavily bearded. He was within fifteen yards before he recognized the ragged, wan-faced men with drooping shoulders as Claus Helberg and Arne Kjelstrup of Grouse and rushed forward to embrace them.

That night at Grouse’s headquarters, a remote hut at Svensbu near Lake Saure, the commandos celebrated with a dinner of reindeer meat supplemented by chocolate and dried fruit brought by the new arrivals. The next morning, 24 February, they began to plan the attack. The location of the heavy water plant, on a lip of rock jutting from a three-thousand-foot mountain and five hundred feet above a river gorge, could hardly have been more impregnable. The only direct route across the gorge was a heavily guarded suspension bridge. The strategy agreed at Farm Hall was that the commandos should cross the gorge somewhere between Rjukan and Vemork and then follow the railway line that ran around the side of the mountain into the plant. First, though, they needed more detailed information. Ronneberg dispatched Claus Helberg to seek details of the latest German deployments from a contact in the Norwegian resistance and then to rendezvous with the main group later that day at another hut nearer the plant.

Helberg returned with important news: Amazing though it seemed, the railway line into the plant was unguarded. However, the critical question remained: Where could the men climb up and out of the river gorge onto the railway? Scrutinizing aerial photographs, they noticed bushes and trees growing up the side of the gorge at a single point. Ronneberg reckoned where plants could grow, men could climb, and he again sent Claus Helberg to reconnoiter. Slipping and sliding down into the ice-bound gorge at a safe distance from the plant, he crept along the frozen river at its base until he reached the bushes and identified “a somewhat passable way” up to the factory.

Читать дальше