Two years later, Stark used the much-feared official weekly SS journal Das Schwarze Korps to brand Heisenberg “a White Jew”—one of the “representatives of Judaism in German spiritual life who must all be eliminated just as the Jews themselves.” With the SS taking an ever-closer interest in him, Heisenberg’s mother, who had known Heinrich Himmler’s mother since childhood, begged Frau Himmler to intercede, and, somewhat grudgingly, she agreed. However, Heisenberg remained under investigation and was summoned several times to the Gestapo’s notorious headquarters in Prinz Albrechtstrasse in Berlin for questioning. He was interrogated in a cellar with, as he recalled, an “ugly inscription” painted on one of the walls: “Breathe deeply and quietly.” Finally, in July 1938, Himmler wrote to Heisenberg that there would be no more attacks. On the same day Himmler also wrote to Reinhard Heydrich, the chief of the Gestapo, that Heisenberg was too valuable to liquidate. Notwithstanding Himmler’s apparent blessing, Heisenberg was still not appointed to Munich University. Instead, a former assistant of Stark’s was given Sommerfeld’s physics chair. He was, in Sommerfeld’s view, a “complete idiot.”

• • •

Einstein severed his links with Germany early and forever. He was about to sail back to Europe from California when Hitler came to power, and roundly denounced the land of his birth for turning its back on “civil liberty, tolerance, and equality of all citizens before the law.” A few days later, in Antwerp, he announced his resignation from the Prussian Academy of Sciences, thereby infuriating the Prussian minister for education, Bernhard Rust, who had hoped to mark the national boycott of Jewish businesses called for 1 April 1933 by expelling him.

As enraged Nazis ransacked Einstein’s house and the authorities confiscated his bank account, Germany’s most famous scientist crossed the Channel to England with his wife, Elsa, protected by a British naval commander and MP who had had the singular experience of having once been invited to kill Rasputin. Einstein was safe but confessed to Max Born, “My heart aches when I think of the young ones.” He also told him that he had never thought highly of “the Germans” but the degree of their brutality and cowardice had surprised even him. In the autumn of 1933, finding England too formal and preferring a life with “no butlers. No evening dress,” Einstein accepted a post at the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton. Paul Langevin, watching events from Paris, thought his emigration highly significant, remarking only half in jest that “it’s as important an event as would be the transfer of the Vatican from Rome to the New World. The Pope of Physics has moved and the United States will now become the centre of the natural sciences.”

• • •

Einstein rounded on German intellectuals for behaving “no better than the rabble.” Certainly, some prevaricated while books by “undesirables” were tossed on fires and professors sympathetic to the new order donned brown shirts to lecture on such absurdities as “Aryan mathematics.” A number hoped that the expulsion of so many scholars would further their own careers. However, many were troubled, and a few, including Max Planck, had the courage to try to help their Jewish colleagues. Planck was given an audience with Hitler on 16 May 1933, but, according to Planck, the führer “whipped himself into such a frenzy” that Planck could only listen in appalled silence, then leave. Heisenberg also considered protesting, despite his fragile personal position. He visited a tired-looking Planck, whose “finely chiseled face,” he thought, “had developed deep creases” and whose smile “seemed tortured.” The initiator of quantum theory, shaken by his encounter with completely irrational forces, convinced Heisenberg that protests would be “utterly futile.”

Heisenberg took Planck’s advice, trying to convince himself that the extremism could not last, even that something good might rise out of the mayhem. However, his optimism seemed naive to the point of absurdity to his Jewish friends. He told Born, “Since… only the very least are affected by the law—you and Franck certainly not… the political revolution could take place without any damage to Gottingen physics…. Certainly in the course of time the splendid things will separate from the hateful.” Heisenberg would later justify his position as one of “inner exile,” during which he sought to protect “the old values” so that something would survive “after the catastrophe.” Looking back after the war, he even suggested that his Jewish friends had faced easier choices than himself. Forced to leave, “at least they had been spared the agonising choice of whether or not they ought to stay on.” “Inner exile” would come to involve many compromises, both conscious and unconscious, for Heisenberg.

• • •

Lise Meitner wondered anxiously what would happen to her. She was an Austrian national, not a German. Also, the Kaiser Wilhehn Institute was not directly under government control, and its staff were not government servants. Nevertheless, she felt threatened and, on 3 May 1933, wrote to her long-term friend and collaborator Otto Hahn, then in the United States, begging him to come home. Hahn, who had received equally disturbing letters from other Jewish friends, hurried back to Berlin to see for himself. He was so shocked that he suggested a group of prominent Aryan academics should protest against the treatment of their Jewish colleagues. Yet, just as he had counseled Heisenberg, Max Planck, on the basis of his own protest, warned that it would be pointless: “If today you assemble 50 such people, then tomorrow 150 others will rise up who want the positions of the former.” Planck believed the best way to protect German science was for the present to keep quiet. In an amoral, practical sense he was right. Once the Jewish academics were gone, German science was allowed to proceed largely unmolested.

Hahn too followed Planck’s advice. Like Heisenberg, he steadfastly refused to join the Nazi Party. He also resigned his lectureship at the University of Berlin to avoid having to participate in Nazi Party meetings. In 1935, on the first anniversary of the death of Fritz Haber—he had died of a heart attack during a visit to Switzerland the year before—Hahn and Max Planck, prompted to action again, organized a memorial service, despite official threats, at which they both spoke. University professors, as government employees, were too nervous to attend, fearing they would be dismissed, but sent their wives in one of the very few concerted gestures of solidarity by the scientific community with those who had been ousted. Planck ended his oration with the words “Haber was true to us, we shall be true to him.”

• • •

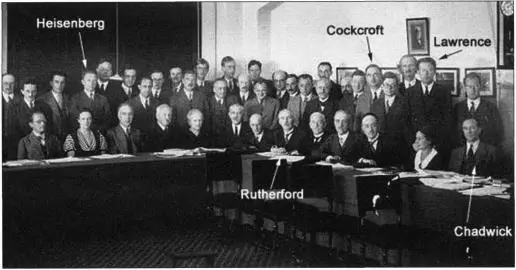

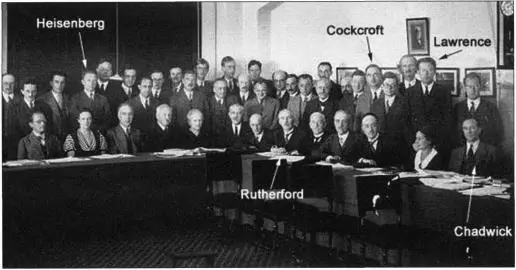

Solvay Conference attendees, 1933

The Solvay Conference of October 1933 in Brussels was a refuge and a distraction from the disturbing happenings in the wider world. Forty experimentalists and theoreticians attended, including Rutherford, Chadwick, Lawrence, Madame Curie, the Joliot-Curies, Langevin, Meitner, and Bohr, to debate the “Structure and Properties of the Atomic Nucleus.” They argued about whether Chadwick’s neutron was a composite of particles or—as experiments would shortly confirm—a particle in its own right. They also discussed the recent finding of another new subatomic particle—the positively charged electron, or “positron”—by Carl Anderson, a physicist at Cal-tech, Pasadena, researching into cosmic radiation. Anderson had made his discovery using a clever device invented many years earlier by the Scotsman Charles Wilson—the cloud chamber—designed to make the invisible path of particles visible. This was achieved by shooting particles through a saturated water vapor created in the chamber, causing them to leave a trail of droplets, like the tail of a meteor. Their track, thus revealed, could be photographed through a window in the side. [19] The discovery of the positron was the first clear indication that the universe consisted of antimatter as well as matter.

Читать дальше