However, the political mood was changing. On Christmas Day 1926a new emperor, the twenty-five-year-old Hirohito, had succeeded to the Japanese imperial throne. The name he chose for his reign was Showa—“illustrious peace”—but the reality would be different. His yearlong enthronement festivities were celebrated with enthusiasm in Hiroshima as well as in the rest of the country. Reverence for the emperor and a desire to separate his divine person from human contact led to the disinfection of cars and trains in which he was to travel and to the requirement for his people not to look at him but to cast down their eyes in his presence. The celebrations reinforced a growing cult of the emperor.

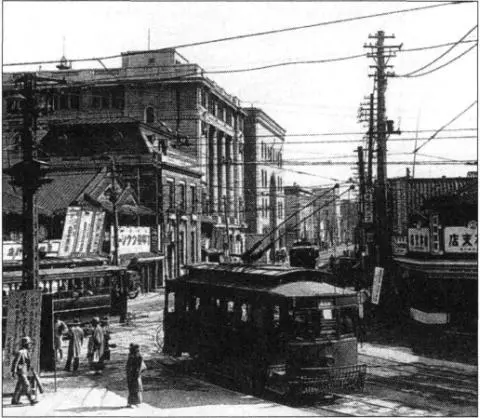

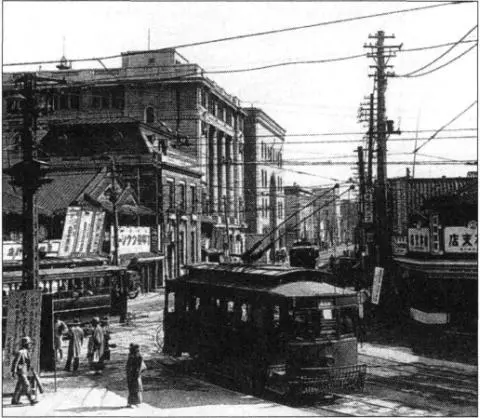

Modern buildings and streetcars in Hiroshima

The early 1930s brought an economic downturn. Turmoil among politicians led to the increasing involvement of the military in the running of all aspects of Japanese life and, at their behest, a further emphasis on the emperor both as a divine religious figure and as the head of a strong and united nation requiring and receiving his subjects’ unquestioning loyalty and obedience. In September 1931 the Japanese military fabricated a crisis—“the Manchurian incident”—as a pretext for their occupation of that much-disputed Chinese province in which Japan had substantial commercial interests and from which it obtained many scarce primary resources. They installed the last emperor of China, Pu Yi, as the puppet emperor of their client state, which they named Manchukuo. When the League of Nations condemned their actions, the Japanese left the league.

In 1932 right-wing officers murdered both the Japanese prime minister and finance minister because they would not follow sufficiently militaristic policies. In the wake of the murders Japan abandoned any kind of party system, and the military’s influence increased further. The cinemas in Hiroshima’s Shintenchi district showed a film called Japan in the National Emergency. The script underlined a growing policy against westernization, and a return to the old values: “In the past we have just followed the western trend without thinking about it… as a result, Japanese pride has faded away…. Today we are lucky to see the revival of the Japanese spirit throughout the nation.” The film disparagingly depicted two westernized young people, in particular a “modern girl” who smokes, dances, and dares to ask a dignified middle-aged gentleman who accidentally steps on her toe in the street to apologize. He refuses, snorting, “This is Japan.” The message was strong: Women should return home, forget Western fashions and behavior, and the Japanese public in general should reject Western mores and glory in Japan’s unique superiority.

SIX

PERSECUTION AND PURGE

ONE NIGHT, Werner Heisenberg had a half-waking “vision.” As he later wrote in his memoirs, he saw a Munich street “bathed in a reddish, increasingly intense and uncanny glow. Crowds of people with scarlet and black-red-and-white flags were streaming from the Victory Gate toward the university fountains and the air was filled with noise and uproar. Suddenly, just in front of me a machine gun began to cough. I tried to jump to safety and woke up.” It was an amalgam of the anarchic scenes he had witnessed as a boy in the Munich of 1919 and of the new, organized National Socialist violence erupting onto Germany’s streets. By 1930 even once moderate and conservative German newspapers were hailing Adolf Hitler as the savior of a Germany deep in financial stagnation. Radical groups of the right and left were fighting in the slums and breaking up each other’s meetings.

Perhaps to forget such things, in January 1933 Heisenberg invited some old friends on a skiing holiday in Bavaria, which, he recalled, was “long remembered by all of us as a beautiful but painful farewell to the ‘golden age’ of atomic physics.” The friends included Niels Bohr and Bohr’s son, Christian, as well as Carl-Friedrich von Weizsacker, whom Heisenberg had known since the latter was fourteen. They had met in 1927 in Copenhagen, where von Weizsacker’s father, later the second most senior official in Hitler’s foreign office, was Germany’s representative in Denmark. The young Carl had read articles by Heisenberg and engineered a meeting with him. Heisenberg, at that time studying under Bohr, was kind to the quiet, academic, awestruck boy and inspired him to become a physicist. Von Weizsacker became not only Heisenberg’s assistant but one of his closest confidants.

The Bohrs arrived at the local railway station after dark, so Heisenberg and von Weizsacker went to meet them. Guiding his guests back up the mountain to the sleeping hut, Heisenberg was peering ahead in the lantern light when he noticed that the snow seemed unusually powdery. Then “something very odd happened—I suddenly had the feeling that I was swimming. I completely lost control of my movements, and then something pressed on me so violently from all sides that, for a moment, I stopped breathing.” The avalanche had not covered his head, and he managed to free his arms. Looking around, he realized he was the only one to have been swept away and had been lucky to survive. Heisenberg and his friends spent their days skiing and talking physics, trying to forget the “world full of political trouble” below the snowline.

Niels Bohr and Werner Heisenberg

One of the first signs of those troubles was the racial laws passed on 7 April 1933, soon after Hitler’s installation as Germany’s new chancellor. The “Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service” banned “non-Aryans”—anyone with at least one Jewish grandparent—from working for the state, and it included the universities as government institutions. There were a few exceptions: Jewish people appointed before the First World War or who had fought or lost fathers or sons at the front.

The Nobel laureate James Franck had served in the war but refused the “privilege” of remaining in his post. On 17 April he resigned his position at Gottingen, protesting, “We Germans of Jewish descent are being treated as aliens and enemies of the Fatherland.” Max Born, who could also have claimed exemption, departed quietly but bitterly, writing, “All I had built up in Gottingen during twelve years’ hard work was shattered.” He went for a walk in the woods “in despair, brooding on how to save my family.” Fritz Haber, the man who, as Franck’s wartime boss, had masterminded Germany’s chemical warfare strategy in the First World War and was a German patriot through and through, also refused his exemption, resigning after being ordered to purge his institute of other “non-Aryans.”

Viewed as a Jewish stronghold, physics attracted special virulence. Two Nobel Prize winners, physicists Johannes Stark and Philipp Lenard, spearheaded the attack. As early as the 1920s they had set themselves up as figureheads of true “German physics,” denouncing the “Jewish physics” of Einstein. Stark had been fired from the University of Würzburg for breaching the rules of the Nobel foundation by using his prize money to buy himself a china factory, but had convinced himself that Jews were responsible for his fall.

Stark and Lenard also attacked the “Jewish-minded” Aryans who took their inspiration from quantum mechanics and relativity. In particular they launched a very personal crusade against Heisenberg for his espousal of “Jewish science” and for being a “Jewish pawn.” In November 1933, when news broke that he had won the Nobel Prize for Physics, Nazi thugs threatened to disrupt his lecture the following day. In 1935, when it seemed likely that Heisenberg would replace his former teacher at Munich University, Arnold Sommerfeld, who was retiring, Stark objected. He denounced Heisenberg as the “spirit of Einstein’s spirit,” deploring that he was “to be rewarded with a call to a chair.”

Читать дальше