Rutherford asked Cockcroft and Walton to temper their jubilation in favor of discretion to allow them time to exploit their discovery without alerting rivals. However, with a media increasingly hungry for further revelations about nuclear physics following Chadwick’s recent discovery of the neutron, soon it seemed only sensible to court press attention. The team chose the Marxist science correspondent of the Manchester Guardian to announce their achievement.

• • •

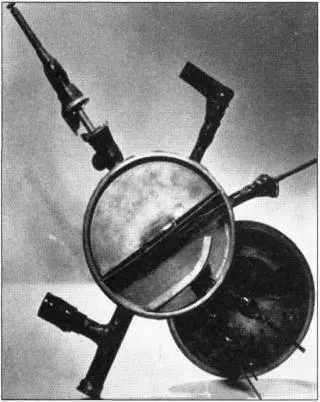

Rutherford had been right to fear competition. The Cavendish might easily have been upstaged by Ernest Lawrence at Berkeley. While Cockcroft and Walton had been busily massaging plasticine over the joints of their accelerator, Lawrence had been developing a successor to his small octopus-armed pillbox. His new cyclotron was an eleven-inch version. In August 1931 his assistant, Milton Stanley Livingston, achieved an energy of over one million electron volts with the new machine-surely enough to accelerate particles to split atoms. Livingston asked Lawrence’s secretary to send him a telegram, which read, “Dr. Livingston has asked me to advise you that he has obtained 1,100,000 volt protons. He also suggested that I add ‘Whoopee!’” When he received it, Lawrence “literally danced around the room,” pale blue eyes shining with excitement and already planning yet bigger, more powerful devices.

Ernest Lawrence’s eleven-inch cyclotron

It was therefore a shock to Lawrence, honeymooning happily in Connecticut in the summer of 1932, to learn that Cockcroft and Walton’s linear accelerator had become the first device to disintegrate the nucleus with accelerated particles. He sent agitated telegraphic orders to Berkeley: “Get lithium from chemistry department and start preparations to repeat with cyclotron. Will be back shortly.” Success was not far off. A few weeks later, the president of the university dispatched a jubilant message to the governor of California: “In September of 1932 artificial disintegration was first accomplished outside of Europe in the Laboratory of Professor Ernest O. Lawrence. This laboratory has taken the lead, in all the world, in the disintegration of the elements.”

• • •

Lawrence had been joined at Berkeley in the autumn of 1929 by a young scientist who shared his ambition to help the United States take “the lead in all the world”: the twenty-five-year-old J. Robert Oppenheimer. Slenderly built, with intensely blue eyes, friends thought him “both subtly wise and terribly innocent.” He was also sensitive, conceited, often neurotic, but charismatically engaging. Though passionate about physics, he was a Renaissance man with obsessions ranging from Hindu philosophy to Dante’s Inferno.

Oppenheimer had grown up in New York, the product of a wealthy, cultured Jewish family whose Riverside Drive apartment was hung with paintings by impressionist masters. He had been, in his own words, “an abnormally, repulsively good little boy.” After attending New York’s exclusive Ethical Culture School, he went on to Harvard. Like many contemporaries in continental Europe, Oppenheimer’s early years were not free of anti-Semitism, albeit differently expressed. He arrived at Harvard shortly after its president had recommended a quota for Jewish undergraduates. When he applied to go and study under Rutherford at the Cavendish, his Harvard professor’s letter of recommendation concluded, in character with the times: “As appears from his name, Oppenheimer is a Jew, but entirely without the usual qualifications of his race. He is a tall, well set-up young man, with a rather engaging diffidence of manner, and I think you need have no hesitation… in considering his application.”

Rutherford, who would never have dreamed of being influenced by matters of race and had a deep contempt for racists, accepted Oppenheimer but was unimpressed by his abilities as an experimentalist. Bohr, while visiting the Cavendish, asked an obviously unhappy Oppenheimer how his work was going. Oppenheimer replied that he was having difficulties. When Bohr asked whether his problems were mathematical or physical, he despairingly said that he didn’t know. Bohr replied with devastating if unhelpful honesty, “That’s bad.” Oppenheimer spent tortured days standing by a blackboard, chalk in hand, but unable to write anything. He could hear himself saying, over and over, “The point is. The point is. The point is….”

Such were Oppenheimer’s inner frustration and turmoil that, during a reunion with a friend, Francis Fergusson, in Paris he became so enraged by something Fergusson said that he leaped on him and tried to strangle him, forcing the more powerfully built Fergusson to fend him off. Back in Cambridge a contrite Oppenheimer wrote to Fergusson, seeking forgiveness for his bizarre behavior and explaining how his failure to live up to “the awful fact of excellence” was tormenting him. He remained troubled, depressed, and occasionally deluded. On one occasion he insisted that he had left a poisoned apple on the desk of a colleague at the Cavendish. For a while a psychiatrist treated him for dementia praecox. There are conflicting stories about why the treatment ended in 1926. According to one, the psychiatrist warned that continuing would do more harm than good. According to the other—and this sounds more likely—Oppenheimer decided he understood more about his condition than his doctor and canceled further sessions. When Max Born visited the Cavendish in 1926 and invited him to Gottingen, Oppenheimer accepted with gratitude but little confidence in his own abilities.

However, Oppenheimer shook off the worst of his depression and mood swings and flourished at Gottingen. More than at either Harvard or Cambridge he felt, in his words, “part of a little community of people who had some common interests and tastes and many common interests in physics.” His passion was theoretical physics, and Gottingen was the focus of the theoretical physics world with all of its leaders teaching there or regularly visiting. Oppenheimer wrote to a friend, “They are working very hard here, and combining a fantastically impregnable metaphysical disingenuousness with the go-getting habits of a wall paper manufacturer. The result is that the work done here has an almost demonic lack of plausibility to it and is highly successful.”

After sampling other leading centers of European theoretical research, Oppenheimer had come home at last. Ten American universities were eager to secure him, and he eventually signed concurrent contracts with two of them: the eight-year-old California Institute of Technology at Pasadena, Cal-tech, where he agreed to teach in the summer, and Berkeley, where he was to teach in autumn and winter. The twenty-five-year-old Oppenheimer loved fast cars but was, he confessed, “a vile driver” who could “scare friends out of all sanity by wheeling corners at seventy.” Unsurprisingly, therefore, when he reached Pasadena after a marathon journey across the States, he had his arm in a sling and his clothes stained with battery acid—the results of a car accident en route.

Oppenheimer had chosen Caltech because he believed its blend of theorists and experimentalists would be good for him—“I would learn, there would be criticism.” His reasons for selecting Berkeley were a little different. Despite possessing Lawrence’s unrivaled experimental facilities, the faculty was weak on the theoretical side, with no one versed in quantum mechanics. Oppenheimer intended to do most of his teaching at Berkeley to remedy these deficiencies and to establish a theoretical and interpretative group to complement Lawrence’s work. In the autumn Oppenheimer arrived at Berkeley ready to begin teaching, fresh from vacationing at the ranch he had just leased in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains of New Mexico. He had named it Perro Caliente at the suggestion of a friend. The words perro caliente are the Spanish translation of the raucous cry of joy—“hot dog!”—he had uttered when he learned the ranch was available. The red, raw beauty of the desert stirred him. He often told friends, “I have two loves, physics and the desert. It troubles me that I don’t see any way to bring them together.”

Читать дальше