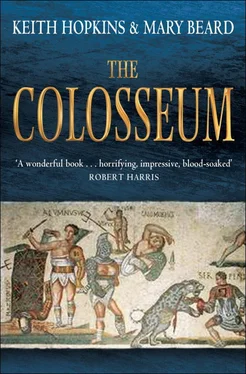

Keith Hopkins - The Colosseum

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Keith Hopkins - The Colosseum» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 2011, ISBN: 2011, Издательство: Profile Books, Жанр: История, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Colosseum

- Автор:

- Издательство:Profile Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- Город:London

- ISBN:9781846684708

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Colosseum: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Colosseum»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Colosseum — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Colosseum», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The Colosseum was the temple of the Sun, of marvellous greatness and beauty, disposed with many diverse vaulted chambers, and all covered with a heaven of gilded bronze where thunders and lightnings and glittering fires were made, and where rain was shed through silver tubes.

In the middle there was supposed to have been a huge statue of Jupiter or Apollo (perhaps a reminiscence of the Colossus) symbolising Roman power. The story went that when Pope Sylvester in the early fourth century had this temple of idolatry destroyed, he had the head and the hands of this statue displayed in front of what was then the principal Christian church in Rome, St John Lateran.

There were other variant medieval theories about the Colosseum. A twelfth-century English traveller known as ‘Master Gregory’ reported that it had been the palace of Vespasian and Titus (a brave attempt presumably to make sense of a remembered connection with those emperors). But it was not until the Italian renaissance humanists got down to work on classical texts, from the fifteenth century onwards, that the building became generally recognised again for the amphitheatre that it had originally been. Even so the connections with magic and demons did not disappear. In the sixteenth century Benvenuto Cellini, the brilliant Florentine jeweller (even if appalling self-promoter and thug), went to the Colosseum on at least two occasions by night in the company of a Sicilian priest (and part-time necromancer) in order to use the black arts to recapture his girlfriend. On the second occasion this proved a rather too successful experiment in summoning the spirits and the necromancers terrified the wits out of themselves. As Cellini explains in his Autobiography , no fumigations seemed effective in persuading the demons to leave – until one of the party in panic ‘let fly such a volley from his breech’ as John Addington Symonds’ delicate translation puts it (‘gave such a blast of a fart accompanied by a vast quantity of shit’ is closer to the demotic Italian) that the evil spirits took to flight. In the morning Cellini and his friends made for home, not entirely certain they had escaped scot-free. In fact, a little boy in the group ‘all the while… kept saying that two of the devils he had seen in the Colosseum were gambolling in front of us, skipping now along the roof and now upon the ground’.

For us, it is hardly possible to imagine the Colosseum being thought of as anything other than an arena of gladiatorial display and animal hunts. But by the eleventh century the connection of the ruined monument with its original function was a distant one. It had not been used for such spectacles for centuries: the last clear record of gladiatorial combat there is in the mid 430s; animal hunts are known to have continued for a century or so more. As late as 523 the Roman senator and bureaucrat Cassiodorus drafted a letter to a consul (responsible for staging hunts in the Colosseum) on behalf of his master, the then ruler of Rome, the Gothic King Theodoric. In it Cassiodorus deplores the cruelty and excesses of the spectacles, while lingering on their details: ‘The first hunter, trusting to a brittle pole, runs on the mouths of the beasts, and seems, in the eagerness of his charge, to desire the death he hopes to avoid… The man’s bent limbs are tossed into the air like flimsy cloths by a lofty spring of his body’; and so on. But Cassiodorus also makes clear that such shows were still extremely popular (even if, as usual in such accounts, there is a trace of the snobbish assumption that the populace will flock to see what their betters rightly disdain); and more to the point he drafts what is effectively Theodoric’s formal authorisation of the shows, urging the consul, as sponsor, to be generous. How much later this continued, however, is anyone’s guess.

It would be comforting if the end of arena spectacles could be pinned directly to the triumph of Christianity. But in fact, when Constantine, the first Christian emperor, came to power at the beginning of the fourth century, his legislation against gladiatorial shows seems to have had about as much visible effect as a thirty-mile-an-hour speed limit at the outskirts of a British town. Besides, Constantine’s policy was not one of outright banning; we have evidence, for example, in an inscription from the central Italian town of Hispellum (modern Spello) that he gave specific permission in the 330s for the local people to hold annual gladiatorial shows there, apparently so that they would not have to make the difficult journey to those in the town of Volsinii. Some laws were certainly passed through the fourth and into the fifth century prohibiting various aspects of arena culture (senators, for example, were banned from using gladiators as bodyguards). But as with the edicts which during the same period outlawed paganism, the reaction was presumably a mixture of obedience, evasion and complete flouting.

In the end it was not so much the legislation (high-minded, religiously driven or not) that put a stop to the bloody spectacles in the Colosseum and elsewhere. Rather, repeated civil wars and barbarian invasions limited the capacity of the state and individuals to sponsor shows, to procure wild animals and (in the case of the Colosseum itself) to keep up a costly, high-maintenance monument. Behind the series of inscriptions which commemorate restorations of the Colosseum at this time probably lie a series of much more amateurish ‘patchingsup’ of an already decaying, down-at-heel, half-abandoned building than we usually imagine (and almost certainly on a smaller scale than these boastful commemorations try to suggest). In parts the building was probably already being quarried for stone in the final stages of its life as an amphitheatre. The Colosseum and its traditional activities were beyond what the resources of Rome in the fifth century could sustain. Constantine had, after all, transferred the principal capital of the empire to Constantinople (modern Istanbul), with all the funding and infrastructure that went with it. And so weakened had Rome itself been by wars, invasions and natural disasters, that the Byzantine historian Procopius estimated that (aristocrats apart) there were only 500 people there when the Gothic KingTotila invaded in 545. Of course, the terrible decline of the late antique city is almost as much a cliché as the overwhelming grandeur of the imperial capital. We should not take Procopius’ figure as a good guide to the usual population of the city at the time (in addition to his likely exaggeration, many inhabitants with means and sense surely left town – as Procopius implies – in advance of Totila’s arrival). Nonetheless this was not a community with either the human or material resources to keep up a monument on this scale even in mothballs, let alone in working order.

It is perhaps no surprise then that when, on 3 September 1332, a bullfight was supposedly held in the Colosseum’s arena in honour of the visit of Ludwig of Bavaria, people at the time do not seem to have made the link with the activities that had taken place there in antiquity. To us, the resemblances are uncanny: we have some more or less contemporary descriptions of bulls maddened by the blows of their human combatants, and striking out fatally at those who had wounded them; the final death toll is said to have been eleven animals and eighteen humans. To most of those watching, the connection between beast hunts and the ancient Colosseum had been forgotten.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Colosseum»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Colosseum» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Colosseum» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.