Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders, and the publishers will be happy to correct mistakes or omissions in future editions.

Martin Amis is the author of two collections of stories, six works of non-fiction, and thirteen novels, most recently Lionel Asbo .

Fiction

The Rachel Papers

Dead Babies

Success

Other People

Money

Einstein’s Monsters

London Fields

Time’s Arrow

The Information

Night Train

Heavy Water

Yellow Dog

The House of Meetings

The Pregnant Widow

Lionel Asbo

Non-fiction

Invasion of the Space Invaders

The Moronic Inferno

Visiting Mrs Nabokov

Experience

The War Against Cliché

The Second Plane

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Version 1.0

Epub ISBN 9781407018546

www.randomhouse.co.uk

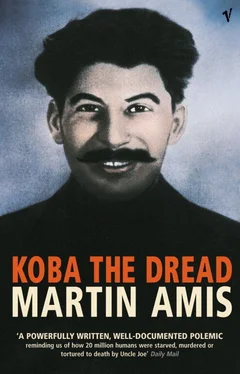

Published by Vintage 2003

4 6 8 10 9 7 5

Copyright © Martin Amis 2002

Martin Amis has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988 to be identified as the author of this work

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

First published in Great Britain in 2002 by Jonathan Cape

Vintage

Random House, 20 Vauxhall Bridge Road,

London SW1V 2SA

www.vintage-books.co.uk

Addresses for companies within The Random House Group Limited can be found at: www.randomhouse.co.uk/offices.htm

The Random House Group Limited Reg. No. 954009

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9780099438021

The millennial moment was midnight, 31 December 2000. This is because we went from B.C. to A.D. without a year nought. Vladimir Putin described the (pseudo) millennium as ‘the 2000th anniversary of Christianity’.

It will be as well, here, to get a foretaste of his rigour. The fate of Mikhail Tukhachevsky, a famous Red commander in the Civil War, was ordinary enough, and that of his family was too. Tukhachevsky was arrested in 1937, tortured (his interrogation protocols were stained with drops of ‘flying’ blood, suggesting that his head was in rapid motion at the time), farcically arraigned, and duly executed. Moreover (this is Robert C. Tucker’s précis in Stalin in Power: The Revolution from Above, 1928–41 ): ‘His wife and daughter returned to Moscow where she was arrested a day or two later along with Tukhachevsky’s mother, sisters, and brothers Nikolai and Aleksandr. Later his wife and both brothers were killed on Stalin’s orders, three sisters were sent to camps, his young daughter Svetlana was placed in a home for children of “enemies of the people” and arrested and sent to a camp on reaching the age of seventeen, and his mother and one sister died in exile.’

Conquest was strongly anti-Vietcong, but his support for the American conduct of the war was never emphatic, and has evolved in the direction of further deemphasis. (Here we may recall that, despite his donnish accent and manner, Conquest is an American. Well, American father, English mother; born in the UK; dual nationality; now a resident of California.) Kingsley was never less than 100 per cent earnest on Vietnam, right up until his death in 1995.

The New Statesman was founded in 1913 by, among others (and the others included Maynard Keynes), the century’s four most extravagant dupes of the USSR: H. G. Wells, George Bernard Shaw, and Sidney and Beatrice Webb. Wells, after an audience with Stalin in 1934, said that he had ‘never met a man more candid, fair and honest’; these attributes accounted for ‘his remarkable ascendancy over the country since no one is afraid of him and everyone trusts him’. Shaw, after some banquet diplomacy, declared the Russian people uncommonly well-fed at a time when perhaps 11 million citizens (Martin Malia, The Soviet Tragedy: A History of Socialism in Russia , 1917–1991) were in the process of dying of starvation. The Webbs, after extensive study, wrote a book which, ‘seen as the last word in serious Western scholarship, ran to over 1,200 pages, representing a vast amount of toil and research, all totally wasted. It was originally entitled Soviet Communism: A New Civilisation? , but the question mark was triumphantly removed in the second edition – which appeared in 1937 at precisely the time the regime was in its worst phase’ (Conquest). Sidney and Beatrice Webb swallowed the great Show Trials of 1936–38, and the New Statesman was not much less sceptical: ‘We do not deny… that the confessions may have contained a substratum of truth’; ‘there had undoubtedly been much plotting in the USSR’; and so on.

What Nabokov characterizes as the Com-pom-poms – Sovnarkom and Narkomindel, and so on; the state liquor monopoly was called Soyuzsprit; the agency shunting the Mandelstams around in the early 1920s was unencouragingly known as Centroevac.

The insurrectionary armies of the Peasant War (1918–22). Lenin, with justice, thought the Greens a greater threat to the regime’s survival than the Whites.

Between 1 January 1917, and 1 January 1923, the price of goods increased by a factor of 100 million.

This made sense doctrinally, too. The Bolsheviks were internationalists; the Soviet Union was no more than the headquarters of Communism while it waited for planetary revolution. As he advanced on Warsaw in July 1920, Marshal Tukhachevsky repeated the official line: ‘Over the corpse of White Poland lies the path to world conflagration.’ (After the Red Army – largely thanks, it seems, to Stalin – was defeated, the Bolsheviks began to suspect that the fraternal revolutions weren’t going to materialize.) As for the Russians themselves, Lenin was frankly racist in his settled dislike for them. They were fools and bunglers, and ‘too soft’ to run an efficient police state. He made no secret of his preference for the Germans.

Though very tardily: the future US president Herbert Hoover had been agitating for a food campaign in the USSR since 1919. Lenin also continued to export grain throughout this period (and continued, of course, to commit vast sums to the fomentation of revolutions elsewhere).

Читать дальше