Martin Amis - Koba the Dread

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Martin Amis - Koba the Dread» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 2003, ISBN: 2003, Издательство: Vintage Books, Жанр: История, Публицистика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

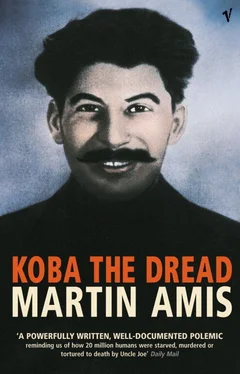

- Название:Koba the Dread

- Автор:

- Издательство:Vintage Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2003

- Город:London

- ISBN:978-0099438021

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Koba the Dread: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Koba the Dread»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

is the successor to Martin Amis’s award-winning memoir,

.

Koba the Dread The author’s father, Kingsley Amis, though later reactionary in tendency, was a “Comintern dogsbody” (as he would come to put it) from 1941 to 1956. His second-closest, and then his closest friend (after the death of the poet Philip Larkin), was Robert Conquest, our leading Sovietologist whose book of 1968,

, was second only to Solzhenitsyn’s

in undermining the USSR. The present memoir explores these connections.

Stalin said that the death of one person was tragic, the death of a million a mere “statistic.”

, during whose course the author absorbs a particular, a familial death, is a rebuttal of Stalin’s aphorism.

Koba the Dread — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Koba the Dread», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

You cannot decide to have brotherhood; if you start trying to enforce it, you will before long find yourself enforcing something very different, and much worse than the mere absence of brotherhood.

And:

The ideal of the brotherhood of man, the building of the Just City, is one that cannot be discarded without lifelong feelings of disappointment and loss.

Sentence one seems to me so obvious, and so elementary, that sentence two has no meaning – indeed, no content. Just what is this Just City? What would it look like? What would its citizens be saying to each other and doing all day? What would laughter be like, in the Just City? (And what would you find to write about in it?) This is the time to start asking why. Zachto? Why? What for? To what end? Your ‘emotional need’ was not a positive but a negative force. Not romantic. Not idealistic. The ‘very nobility’ of that ideal, you say, ‘makes the results of its breakdown doubly horrifying’. But the breakdown, the ignobility, is inherent in the ideal. This is the joke, isn’t it? And it’s a joke about human nature: the absurd assiduity, the droll dispatch, with which utopia becomes dystopia, with which heaven becomes hell… The ‘conflict’ you describe is, in the end, not a conflict between ‘feeling and intelligence’. It is, funnily enough, a conflict between hope and despair.

I quote the following with only token complacency (it is not merely ‘derivative’, as claimed; it is kleptomaniacal):

‘…although Eden, then, is the “goal” of human life, it remains strictly an imaginative goal, not a social construct, even as a possibility. The argument applies also to the literary utopias, which are not the dreary fascist states popularisers try to extrapolate from them, but, rather, analogies of the well-tempered mind: rigidly disciplined, highly selective as regards art, and so on. Thus Blake, like Milton, saw the hidden world, the animal world in which we are condemned to live, as the inevitable complement to man’s imagination. Man was never meant to escape death, jealousy, pain, libido – what Wordsworth calls “the human heart by which we live”. Perhaps this is why Blake paints the created Adam with a serpent already coiled round his thigh.’

So ended my short, derivative, Roget -roughaged essay…

When I wrote that I was about twenty-two; and my student narrator was nineteen – the same age as you were when you ‘joined’. And so, Dad, probably to my detriment, I never felt the call of political faith (and probably one should feel it, one should be zealous, for a while). Nobody can be ‘against’ the Just City. This is among the reasons people feel entitled to kill people who get in the way of it. But when you threw in your lot with the agnostics, the gradualists (and also found another ideology: anti-Communism), you aligned yourself with those who have more faith in human nature than the believers. More faith in – and more affection for. Enough. And now the happier ending.

Anonymously present at Sally’s funeral was Sail’s daughter. Remember, you and I saw her when she was a baby (in the summer of 1979), just before her adoption. The baby, who was perfect, was called Heidi, named after Sally’s very unencouraging new mentor. She is not called Heidi any longer. Sally, then, was twenty-four. Catherine, now, is twenty-two.

She had never met her mother. The funeral was supposed to be a goodbye to her birth identity. As we reconstructed it later, though, she saw our clan at the church and thought – that’s my clan too. She wrote to ‘The Amis Family’ via the undertaker (and what a sinister word that turns out to be). I wrote back: we would meet. A little later, when it was all becoming very much worse for me (the cud in my throat tasted like a decisive diminution of love of life), I wrote again. I said that soon I would be going for three months to the other side of the world; and before I could do that I needed to see the semblance of my sister. She came (with her foster-parents), and she was perfect. You will have to imagine the strange precision of the way she physically occupied the space that Sally had vacated – the same weight of presence, and then a certain smile, a certain glance.

Last spring we took her to Spain to meet her grandmother, and her step-grandfather, and her uncles Philip and Jaime. Catherine was also accompanied by four cousins: my Louis and Jacob, whom you will admiringly remember, and my Fernanda and Clio, two of the three granddaughters you never met. So all your grandchildren were there bar two: my Delilah Seale, and Philip’s Jessica. The clan suffers its losses but continues to expand. There have been four additions in the last six years. Mum said that if we spring too many more grandchildren on her she’s going to have to start strangling them like kittens. Catherine said afterwards, ‘It was like a dream.’ I know you would have taken to her very much, and especially and instantly for this proof of both her nature and her nurture: she’s one of the last thirty or forty people in the English-speaking world who doesn’t say ‘between you and I’.

Last winter, over in Uruguay, as we were about to begin our evening game of catch, Fernanda, who had just turned four, seized the ball with a look of demure triumph on her face. The ball was an inflated globe; and on its surface a dead bee had alighted. The bees were dying in their hundreds as the southern summer ended. They would fizz greedily around the lamps on the veranda, then drop. This was the thing they wanted to do before they died… Of course, a dead bee can still sting. Fernanda’s smile abruptly disappeared and she said in a strong, proud, declarative voice (before shedding the necessary tears), ‘Something just hurt me very much .’ Well, that was exactly how I was feeling about Sally’s death. Remembering her, and you, and you and her, has filled me with an exhaustion that no amount of sleep can seem to reach. But the exhaustion is not onerous. It is appropriate. It feels like decorum. Naturally, it feels like self-pity, too. But pity and self-pity can sometimes be the selfsame thing. Death does that. Don’t you find?

Stalin (whom, incredibly, you served for twelve years, inconspicuously, infinitesimally – but still incredibly) once said that, while every death is a tragedy, the death of a million is a mere statistic. The second half of the aphorism is of course wholly false: a million deaths are, at the very least, a million tragedies. The first half of the aphorism is perfectly sound – but only as far as it goes. In fact, every life is a tragedy, too. Every life cleaves to the tragic curve.

This letter comes at the end of a book subtitled ‘Laughter and the Twenty Million’. You might consider it an odd conclusion. Sally, of course, has nothing whatever in common with the Twenty Million. Nothing but death, and perhaps a semblance of reawakening.

Your middle child hails you and embraces you.

Permissions

The author and publishers wish to thank the following for permission to reprint copyright material:

The Estate of Vladimir Nabokov for permission to reprint material from Dear Bunny, Dear Volodya: The Nabokov-Wilson Letters, 1940–1971 edited by Simon Karlinsky, all rights reserved; Viking Penguin, a Division of Penguin Putnam, Inc. for permission to reprint material from Kolyma: The Arctic Death Camps by Robert Conquest © 1978 by Robert Conquest; HarperCollins Publishers Ltd for permission to reprint material from Forever Flowing: A Novel by Vasily Grossman, translated by Thomas P. Whitney © 1970 by Possev-Verlag, English translation © 1972 by Thomas P. Whitney and material from The Rise and Fall of the Soviet Union by Dmitri Volkogonov, translated and edited by Harold Shukman © 1998 Novosti Publishers, English translation © 1998 by Harold Shukman; The Random House Group Ltd and HarperCollins Publishers, Inc. for permission to reprint 1370 words from The Gulag Archipelago 1918–1956: An Experiment in Literary Investigation I–II by Aleksandr I. Solzhenitsyn © 1973 by Aleksandr I. Solzhenitsyn, English translation © 1973, 1974 by Harper & Row Publishers, Inc., published by The Harvill Press, and 730 words from The Gulag Archipelago 1918–1956: An Experiment in Literary Investigation III-IV by Aleksandr I. Solzhenitsyn © 1974 by Aleksandr I. Solzhenitsyn, English translation © 1975 by Harper & Row Publishers, Inc., published by The Harvill Press; Curtis Brown, Ltd and Oxford University Press, Inc. for permission to reprint material from The Harvest of Sorrow by Robert Conquest © 1986 by Robert Conquest, material from Stalin and the Kirov Murder by Robert Conquest © 1989 by Robert Conquest and material from The Great Terror: A Reassessment by Robert Conquest © 1990 by Robert Conquest; Curtis Brown, Ltd and W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. for permission to reprint material from Reflections on a Ravaged Century by Robert Conquest © 1999 by Robert Conquest; The Free Press, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. and Robert I. Ducas for permission to reprint material from Lenin: A New Biography by Dmitri Volkogonov, translated by Harold Shukman © 1994 by Dmitri Volkogonov, English translation © 1994 by Harold Shukman; The Free Press, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. for permission to reprint material from The Soviet Tragedy: A History of Socialism in Russia, 1917–1991 by Martin Malia © 1994 by Martin Malia; The Harvill Press for permission to reprint material from The KGB’s Literary Archive by Vitaly Shentalinsky © 1993 Editions Robert Laffont, Paris, English translation © 1995 by The Harvill Press; Alfred A. Knopf, a Division of Random House, Inc. for permission to reprint material from The Russian Revolution by Richard Pipes © 1990 by Richard Pipes; Penguin Books Ltd, for permission to reprint material from Kolyma Tales by Varlam Shalamov, translated by John Glad (Penguin Classics, 1994) © 1980, 1981, 1994 by John Glad; Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass.: for permission to reprint material from pp. 274, 725, 149, 161–162, 166, 164, 165, 168 of The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression by Stéphane Courtois, Nicholas Werth, Jean-Louis Panné, Andrzej Packowski, Karel Bartoöek, and Jean-Louis Margolin, translated by Jonathan Murphy and Mark Kramer © 1999 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College, all rights reserved, first published in France as Le livre noir du communisme: Crimes, terreur, répression © 1997 Editions Robert Laffont, S.A., Paris; The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass.: for permission to reprint material from p. 80 of Russia Under Western Eyes: From the Bronze Horseman to the Lenin Mausoleum by Martin Malia © 1999 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College; W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. for permission to reprint material from Stalin in Power: The Revolution from Above, 1928–1941 by Robert C. Tucker © 1990 by Robert C. Tucker; The Random House Group Ltd for permission to reprint material from Three ‘Whys’ of the Russian Revolution by Richard Pipes © 1995 by Richard Pipes, published by Pimlico; Simon & Schuster UK Ltd for permission to reprint material from Man is Wolf to Man: Surviving the Gulag by Janusz Bardach and Kate Gleeson © 1998 by Janusz Bardach and Kate Gleeson; The New Press (800–253–4830) for permission to reprint material from Intimacy and Terror: Soviet Diaries of the 1930s edited by Véronique Garros, Natalia Korenevskaya, and Thomas Lahusen © 1995; The Society of Authors, on behalf of the Laurence Binyon Estate for permission to reprint material from ‘For the Fallen’ (September 1914); Harcourt, Inc. for permission to reprint material from Journey Into the Whirlwind by Eugenia Semyonovna Ginzburg © 1967 by Arnoldo Mondadori Editore-Milano, English translation by Paul Stevenson and Max Hayward © 1967 by Harcourt Inc.; The New Statesman for permission to reprint material from Weekend Competition No. 2372 by Robin Ravenbourne and Basil Ransome, first published in the New Statesman in the issue dated 29 August 1975 © New Statesman Ltd, all rights reserved; Weidenfeld & Nicholson, a Division of the Orion Publishing Group Ltd for permission to reprint material from Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime by Richard Pipes, material from Stalin: Triumph and Tragedy by Dmitri Volkogonov, translated by Harold Shukman © 1991 by Harold Shukman and material from Stalin: Breaker of Nations by Robert Conquest © 1991 by Robert Conquest; The Stationary Office Ltd for permission to reprint material from The Russian Revolution, 1917 ; The Marvell Press, England and Australia for permission to reprint ‘Born Yesterday’ from The Less Deceived , by Philip Larkin.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Koba the Dread»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Koba the Dread» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Koba the Dread» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.