David Deutch - The Fabric of Reality

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «David Deutch - The Fabric of Reality» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. ISBN: , Жанр: Физика, Философия, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Fabric of Reality

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:0-7139-9061-9

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 2

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Fabric of Reality: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Fabric of Reality»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Fabric of Reality — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Fabric of Reality», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

This last type of problem resembles stage 1 of the inductivist scheme, but only superficially. For an unexpected observation never initiates a scientific discovery unless the pre-existing theories already contain the seeds of the problem. For example, clouds wander even more than planets do. This unpredictable wandering was presumably familiar long before planets were discovered. Moreover, predicting the weather would always have been valuable to farmers, seafarers and soldiers, so there would always have been an incentive to theorize about how clouds move. Yet it was not meteorology that blazed the trail for modern science, but astronomy. Observational evidence about meteorology was far more readily available than in astronomy, but no one paid much attention to it, and no one induced any theories from it about cold fronts or anticyclones. The history of science was not crowded with disputes, dogmas, heresies, speculations and elaborate theories about the nature of clouds and their motion. Why? Because under the established explanatory structure for weather, it was perfectly comprehensible that cloud motion should be unpredictable. Common sense suggests that clouds move with the wind. When they drift in other directions, it is reasonable to surmise that the wind can be different at different altitudes, and is rather unpredictable, and so it is easy to conclude that there is no more to be explained. Some people, no doubt, took this view about planets, and assumed that they were just glowing objects on the celestial sphere, blown about by high-altitude winds, or perhaps moved by angels, and that there was no more to be explained. But others were not satisfied with that, and guessed that there were deeper explanations behind the wandering of planets. So they searched for such explanations, and found them. At various times in the history of astronomy there appeared to be a mass of unexplained observational evidence; at other times only a scintilla, or none at all. But always, if people had chosen what to theorize about according to the cumulative number of observations of particular phenomena, they would have chosen clouds rather than planets. Yet they chose planets, and for diverse reasons. Some reasons depended on preconceptions about how cosmology ought to be, or on arguments advanced by ancient philosophers, or on mystical numerology. Some were based on the physics of the day, others on mathematics or geometry. Some have turned out to have objective merit, others not. But every one of them amounted to this: it seemed to someone that the existing explanations could and should be improved upon.

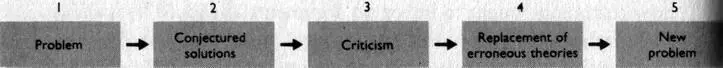

One solves a problem by finding new or amended theories, containing explanations which do not have the deficiencies, but do retain the merits, of existing explanations (Figure 3.2). Thus, after a problem presents itself (stage 1), the next stage always involves conjecture: proposing new theories, or modifying or reinterpreting old ones, in the hope of solving the problem (stage 2). The conjectures are then criticized which, if the criticism is rational, entails examining and comparing them to see which offers the best explanations, according to the criteria inherent in the problem (stage 3). When a conjectured theory fails to survive criticism — that is, when it appears to offer worse explanations than other theories do — it is abandoned. If we find ourselves abandoning one of our originally held theories in favour of one of the newly proposed ones (stage 4), we tentatively deem our problem-solving enterprise to have made progress. I say ‘tentatively’, because subsequent problem-solving will probably involve altering or replacing even these new, apparently satisfactory theories, and sometimes even resurrecting some of the apparently unsatisfactory ones. Thus the solution, however good, is not the end of the story: it is a starting-point for the next problem-solving process (stage 5). This illustrates another of the misconceptions behind inductivism. In science the object of the exercise is not to find a theory that will, or is likely to, be deemed true for ever; it is to find the best theory available now, and if possible to improve on all available theories. A scientific argument is intended to persuade us that a given explanation is the best one available. It does not and could not say anything about how that explanation will fare when, in the future, it is subjected to new types of criticism and compared with explanations that have yet to be invented. A good explanation may make good predictions about the future, but the one thing that no explanation can even begin to predict is the content or quality of its own future rivals.

FIGURE 3.2 The problem-solving process.

What I have described so far applies to all problem-solving, whatever the subject-matter or techniques of rational criticism that are involved. Scientific problem-solving always includes a particular method of rational criticism, namely experimental testing. Where two or more rival theories make conflicting predictions about the outcome of an experiment, the experiment is performed and the theory or theories that made false predictions are abandoned. The very construction of scientific conjectures is focused on finding explanations that have experimentally testable predictions. Ideally we are always seeking crucial experimental tests — experiments whose outcomes, whatever they are, will falsify one or more of the contending theories. This process is illustrated in Figure 3.3. Whether or not observations were involved in the instigating problem (stage 1), and whether or not (in stage 2) the contending theories were specifically designed to be tested experimentally, it is in this critical phase of scientific discovery (stage 3) that experimental tests play their decisive and characteristic role. That role is to render some of the contending theories unsatisfactory by revealing that their explanations lead to false predictions. Here I must mention an asymmetry which is important in the philosophy and methodology of science: the asymmetry between experimental refutation and experimental confirmation. Whereas an incorrect prediction automatically renders the underlying explanation unsatisfactory, a correct prediction says nothing at all about the underlying explanation. Shoddy explanations that yield correct predictions are two a penny, as UFO enthusiasts, conspiracy-theorists and pseudo-scientists of every variety should (but never do) bear in mind.

If a theory about observable events is untestable — that is, if no possible observation would rule it out — then it cannot by itself explain why those events happen in the way they are observed to and not in some other way. For example, the ‘angel’ theory of planetary motion is untestable because no matter how planets moved, that motion could be attributed to angels; therefore the angel theory cannot explain the particular motions that we see, unless it is supplemented by an independent theory of how angels move. That is why there is a methodological rule in science which says that once an experimentally testable theory has passed the appropriate tests, any less testable rival theories about the same phenomena are summarily rejected, for their explanations are bound to be inferior. This rule is often cited as distinguishing science from other types of knowledge-creation. But if we take the view that science is about explanations, we see that this rule is really a special case of something that applies naturally to all problem-solving: theories that are capable of giving more detailed explanations are automatically preferred. They are preferred for two reasons. One is that a theory that ‘sticks its neck out’ by being more specific about more phenomena opens up itself and its rivals to more forms of criticism, and therefore has more chance of taking the problem-solving process forward. The second is simply that, if such a theory survives the criticism, it leaves less unexplained — which is the object of the exercise.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Fabric of Reality»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Fabric of Reality» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Fabric of Reality» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.