David Deutch - The Fabric of Reality

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «David Deutch - The Fabric of Reality» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. ISBN: , Жанр: Физика, Философия, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Fabric of Reality

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:0-7139-9061-9

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 2

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Fabric of Reality: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Fabric of Reality»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Fabric of Reality — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Fabric of Reality», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

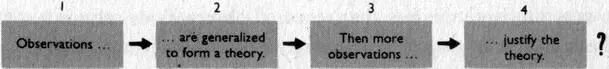

This is known as the ‘problem of induction’. The name derives from what was, for most of the history of science, the prevailing theory of how science works. The theory was that there exists, short of mathematical proof, a lesser but still worthy form of justification called induction. Induction was contrasted, on the one hand, with the supposedly perfect justification provided by deduction, and on the other hand with supposedly weaker philosophical or intuitive forms of reasoning that do not even have observational evidence to back them up. In the inductivist theory of scientific knowledge, observations play two roles: first, in the discovery of scientific theories, and second, in their justification. A theory is supposed to be discovered by ‘extrapolating’ or ‘generalizing’ the results of observations. Then, if large numbers of observations conform to the theory, and none deviates from it, the theory is supposed to be justified — made more believable, probable or reliable. The scheme is illustrated in Figure 3.1.

The inductivist analysis of my discussion of shadows would therefore go something like this: ‘We make a series of observations of shadows, and see interference phenomena (stage 1). The results conform to what would be expected if there existed parallel universes which affect one another in certain ways. But at first no one notices this. Eventually (stage 2) someone forms the generalization that interference will always be observed under the given circumstances, and thereby induces the theory that parallel universes are responsible. With every further observation of interference (stage 3) we become a little more convinced of that theory. After a sufficiently long sequence of such observations, and provided that none of them ever contradicts the theory, we conclude (stage 4) that the theory is true. Although we can never be absolutely sure, we are for practical purposes convinced.’

It is hard to know where to begin in criticizing the inductivist conception of science — it is so profoundly false in so many different ways. Perhaps the worst flaw, from my point of view, is the sheer non sequitur that a generalized prediction is tantamount to a new theory. Like all scientific theories of any depth, the theory that there are parallel universes simply does not have the form of a generalization from the observations. Did we observe first one universe, then a second and a third, and then induce that there are trillions of them? Was the generalization that planets will ‘wander’ round the sky in one pattern rather than another, equivalent to the theory that planets are worlds, in orbit round the Sun, and that the Earth is one of them? It is also not true that repeating our observations is the way in which we become convinced of scientific theories. As I have said, theories are explanations, not merely predictions. If one does not accept a proposed explanation of a set of observations, making the observations over and over again is seldom the remedy. Still less can it help us to create a satisfactory explanation when we cannot think of one at all.

FIGURE 3.1 The inductivist scheme.

Furthermore, even mere predictions can never be justified by observational evidence, as Bertrand Russell illustrated in his story of the chicken. (To avoid any possible misunderstanding, let me stress that this was a metaphorical, anthropomorphic chicken, representing a human being trying to understand the regularities of the universe.) The chicken noticed that the farmer came every day to feed it. It predicted that the farmer would continue to bring food every day. Inductivists think that the chicken had ‘extrapolated’ its observations into a theory, and that each feeding time added justification to that theory. Then one day the farmer came and wrung the chicken’s neck. The disappointment experienced by Russell’s chicken has also been experienced by trillions of other chickens. This inductively justifies the conclusion that induction cannot justify any conclusions!

However, this line of criticism lets inductivism off far too lightly. It does illustrate the fact that repeated observations cannot justify theories, but in doing so it entirely misses (or rather, accepts) a more basic misconception: namely, that the inductive extrapolation of observations to form new theories is even possible. In fact, it is impossible to extrapolate observations unless one has already placed them within an explanatory framework. For example, in order to ‘induce’ its false prediction, Russell’s chicken must first have had in mind a false explanation of the farmer’s behaviour. Perhaps it guessed that the farmer harboured benevolent feelings towards chickens. Had it guessed a different explanation — that the farmer was trying to fatten the chickens up for slaughter, for instance — it would have ‘extrapolated’ the behaviour differently. Suppose that one day the farmer starts bringing the chickens more food than usual. How one extrapolates this new set of observations to predict the farmer’s future behaviour depends entirely on how one explains it. According to the benevolent-farmer theory, it is evidence that the farmer’s benevolence towards chickens has increased, and that therefore the chickens have even less to worry about than before. But according to the fattening-up theory, the behaviour is ominous — it is evidence that slaughter is imminent.

The fact that the same observational evidence can be ‘extrapolated’ to give two diametrically opposite predictions according to which explanation one adopts, and cannot justify either of them, is not some accidental limitation of the farmyard environment: it is true of all observational evidence under all circumstances. Observations could not possibly play either of the roles assigned to them in the inductivist scheme, even in respect of mere predictions, let alone genuine explanatory theories. Admittedly, inductivism is based on the common-sense theory of the growth of knowledge — that we learn from experience — and historically it was associated with the liberation of science from dogma and tyranny. But if we want to understand the true nature of knowledge, and its place in the fabric of reality, we must face up to the fact that inductivism is false, root and branch. No scientific reasoning, and indeed no successful reasoning of any kind, has ever fitted the inductivist description.

What, then, is the pattern of scientific reasoning and discovery? We have seen that inductivism and all other prediction-centred theories of knowledge are based on a misconception. What we need is an explanation-centred theory of knowledge: a theory of how explanations come into being and how they are justified; a theory of how, why and when we should allow our perceptions to change our world-view. Once we have such a theory, we need no separate theory of predictions. For, given an explanation of some observable phenomenon, it is no mystery how one obtains predictions. And if one has justified an explanation, then any predictions derived from that explanation are automatically justified too.

Fortunately, the prevailing theory of scientific knowledge, which in its modern form is due largely to the philosopher Karl Popper (and which is one of my four ‘main strands’ of explanation of the fabric of reality), can indeed be regarded as a theory of explanations in this sense. It regards science as a problem-solving process. Inductivism regards the catalogue of our past observations as a sort of skeletal theory, supposing that science is all about filling in the gaps in that theory by interpolation and extrapolation. Problem-solving does begin with an inadequate theory — but not with the notional ‘theory’ consisting of past observations. It begins with our best existing theories. When some of those theories seem inadequate to us, and we want new ones, that is what constitutes a problem. Thus, contrary to the inductivist scheme shown in Figure 3.1, scientific discovery need not begin with observational evidence. But it does always begin with a problem. By a ‘problem’ I do not necessarily mean a practical emergency, or a source of anxiety. I just mean a set of ideas that seems inadequate and worth trying to improve. The existing explanation may seem too glib, or too laboured; it may seem unnecessarily narrow, or unrealistically ambitious. One may glimpse a possible unification with other ideas. Or a satisfactory explanation in one field may appear to be irreconcilable with an equally satisfactory explanation in another. Or it may be that there have been some surprising observations — such as the wandering of planets — which existing theories did not predict and cannot explain.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Fabric of Reality»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Fabric of Reality» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Fabric of Reality» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.