Schachtel set forth another trait of symbolic behavior when he observed the genesis of an attitude among children which he called “autonomous object interest,” an attitude which he was careful to distinguish from need-satisfactions and wish fulfillment. It is not difficult, I think, to demonstrate that this autonomous object interest is intimately associated with the genesis of object language in the second year of life and is in fact an enduring trait of all symbolic behavior.

Two observations by Martin Buber are also of the utmost relevance to the basic structure of symbolic behavior. One of the main theses of Buber’s thought is his concept of relation, or the interhuman, which he holds to be beyond the reach of a behavioristic psychology. The other is the concept of distance. In contrast to the organism which exists wholly within its environment, man sets things at a distance. He is the creature through whose being (Sein), a phenomenon, “what is” (das Seiende), becomes detached from him and recognized for itself. Buber’s observations are developed within the framework of a philosophical anthropology; the traits of distance and relation are expressed as modes peculiar to human existence rather than as directly observable features of human relations. Expressed thus, Buber’s insights are perhaps somewhat uncongenial to many American social scientists with their strict empirical methodology — although it would be quite possible to defend the thesis that Buber’s analysis of human existence and human relations is also empirical in the broad sense of the word. It may be true that these existential traits of distance and relation are not “mental,” but they must strike the empirical scientist as vague in meaning and difficult to define operationally. Man is after all an organism, whatever else he is, and he does live in an environment. If he exists in uniquely human modes of being, such as distance and relation, it is not clear how these modes are grounded in or otherwise related to the present empirical knowledge of man. Precisely what does it mean to say that the human organism enters into the interhuman relation and sets things at a distance? Such theoretical grounding is, I believe, forthcoming from an empirical analysis of symbolic behavior. Indeed, it seems clear that Ruesch and Jaffe’s more-than-one-person system, Schachtel’s autonomous object interest, and Buber’s distance and relation are neither random nor reducible characteristics of human behavior. They are rather among the prime and generic traits of the highly structured meaning-situation found in symbolic behavior. What is more important, these traits are ascertainable not by a philosophical anthropology — which source is itself enough to render them suspect in the eyes of the behavioral scientists — but by an empirical analysis of language events as they are found to occur in the genetic appearance of language in the encultured child, in blind deaf-mutes, and in the structure of everyday language exchanges.

The greatest danger of the narrow behavioristic framework within which American behavioral scientists almost instinctively conceive the interpersonal process is that peculiarly human phenomena, such as language, are held either reducible to response sequences which leave out symbols altogether, or else describable by analogy, which does not so much shed light on the subject as close the door. Thus it may be unexceptionable to compare genes and symbols as the permanent characters of their respective systems and to speak of “levels of organization,” but such semantic shifts shed little or no light on intersubjective processes.* In an article about Buber, Leslie Farber wrote not long ago, “Having used only the single mode of scientific knowledge for the past hundred years or so, we are uneasily aware that this was the wrong mode — the wrong viewpoint, the wrong terminology, and the wrong kind of knowledge — ever to explain the human being.” This is true enough, I believe. There is a danger, however, in setting philosophical anthropology over against empirical science in such a sharp dichotomy. It is apt to confirm the positive scientist in his determination to have nothing to do with the existentialist-phenomenological movement — and so further impoverishes his social behaviorism. At the same time it encourages from the opposite quarter all manner of irrational and antiscientific prejudice — in particular the ill-assorted crew of post-Cartesian mentalists who want to rescue “man” from “science” and restore him to the angelic order of mind and subjectivity. No, the present crisis of the social sciences need not polarize itself into an ideological issue between American positivists and European existentialists. Surely the better course is an allegiance to the empirical method — but not, let me carefully note, an allegiance to a theoretical commitment. The watchword of the empirical social scientist who confronts interpersonal phenomena should be, Let us see what is going on , and not, Let us see how we can fit it into a stimulus-response transaction.

The Structure of Symbolic Behavior

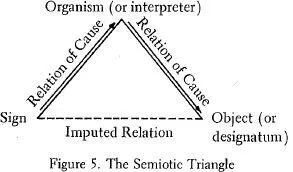

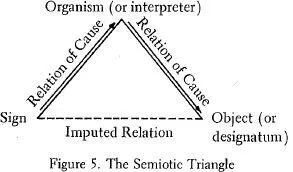

It would not, perhaps, be inaccurate to say that American psychology, as well as other behavioral sciences, has settled on an eclectic behaviorism in which the cruder features of Watsonian psychology have been refined by the work of Tolman, Skinner, Hull, Mowrer, Dollard and Miller, Sears, and Angyall. In this view, also put forward at the pragmatic level of semiotic, the organism, whether human or subhuman, is regarded as an open system living in an environment and adapting to that environment through its response to elements which are called signs. A sign is defined as an element in the environment which, through congenital or acquired patterns of behavior, directs the organism to something else, this something else being understood either as some other element or simply as biologically relevant behavior. Thus, the scent of deer directs the tiger to the deer; the scent of the tiger directs the deer to flight. A good representation of this relation is the semiotic triangle, shown in Figure 5.*

The relations between signs and interpreters and between interpreters and objects are of the nature of space-time transactions between an organism and its environment and can be studied by a natural science. The relation between sign and object, shown in Figure 5 as dotted, has been called an imputed, as opposed to a real, relation. But this imputed relation is ambiguous. Does it mean that naming is folly and not the fit subject of a natural science, or does it mean that it is a formal relation and open to study only by a formal science? But naming does happen. People give names to things as surely as rats find their way through mazes.

The problem, it would seem, is how to give an account of symbolic behavior considered not in its formal aspects — as it would be considered by grammar, logic, and mathematics — but as a happening and, as such, open to a natural science.

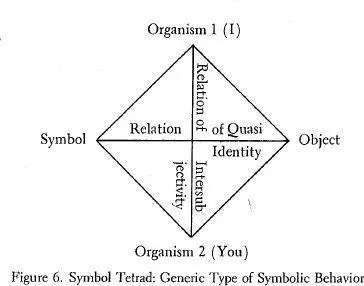

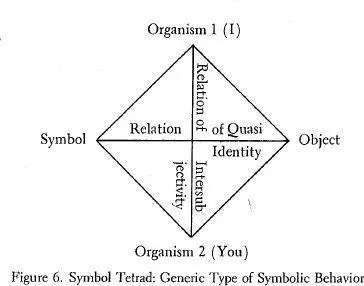

Although the semiotic triangle is a useful model of stimulus-response arcs and of learning behavior, the fact is that symbolic behavior is irreducibly tetradic in structure, as shown in Figure 6.*

The second person is required as an element not merely in the genetic event of learning language but as the indispensable and enduring condition of all symbolic behavior. The very act of symbolic formulation, whether it be language, logic, art, or even thinking, is of its very nature a formulation for a someone else. Even Robinson Crusoe, writing in his journal after twenty years on the island, is nevertheless performing a through-and-through social and intersubjective act.†

Читать дальше