Jared Diamond - The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Jared Diamond - The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1991, ISBN: 1991, Издательство: RADIUS, Жанр: Биология, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee

- Автор:

- Издательство:RADIUS

- Жанр:

- Год:1991

- ISBN:0-09-174268-4

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Today, most European languages and many Asian languages as far as India are very similar to each other (see table of vocabulary overle; No matter how we complain while memorizing French word lists school, these so-called 'Indo-European' languages resemble English, each other, and differ from all the world's other languages, in vocabul and grammar. Only 140 of the modern world's 5,000 tongues belong this language family, but their importance is far out of proportion to tt numbers. Thanks to the global expansion of Europeans since 149! especially of people from England, Spain, Portugal, France, and Russi nearly half the world's present population of five billion now speaks Indo-European language as its native tongue.

To us it may seem perfectly natural, and in no need of further explanation, that most European languages resemble each other, until we go to parts of the world with great linguistic diversity do realize how weird is Europe's homogeneity, and how it cries out explanation. For example, in areas of the New Guinea highlands where I work and where first contact with the outside world began only in the Twentieth Century, languages as different as Chinese is from English replace each other over short distances (Chapter Thirteen). Eurasia must also have been diverse in its pre-first-contact condition, and gradually become less so until finally some people speaking the mother tongue of the Indo-European language family steamrollered almost all other European languages out of existence.

INDO-EUROPEAN LANGUAGES

English one two three mother brother sister

German ein zwei drei Mutter Bruder Schwester

French un deux trois mere frere soeur

Latin unus duo tres mater frater soror

Russian odin dva tri mat' brat sestra

Old Irish oen do tri mathir brathir siur

Tocharia sas wu trey macer procer ser

Lithuania vienas du trys motina brolis seser

Sanskrit eka duva trayas matar bhratar svasar

PIE oynos dwo treyes mater bhrater suesor

NON-INDO-EUROPEAN LANGUAGES

Finnish yksi kaksi kolme aiti veli sisar

Fore ka tara kakaga nano naganto nanona

PIE stands for proto-Indo-European, the reconstructed mother tongue of the first Indo-Europeans. Fore is a language of the New Guinea Highlands. Note that most words are very similar among the Indo-European languages and totally different among the non-Indo-European languages.

Of all the processes by which the modern world lost its earlier linguistic diversity, the Indo-European expansion has been the most important. Its first stage, which long ago carried Indo-European languages over Europe and much of Asia, was followed by a second stage that began in 1492 and carried them to all other continents (Chapter Fourteen). When and where did the steamroller start, and what gave it its power? Why was Europe not overrun instead by speakers of a language related to, say, Finnish or Assyrian?

While the Indo-European problem is the most famous problem of historical linguistics, it is a problem of archaeology and history as well. In the case of those Europeans who carried out the second stage of the Indo-European expansion beginning in 1492, we know not only their vocabulary and grammar but also the ports where they set out, the dates of their sailings, the names of their leaders, and why they succeeded in conquering (Chapter Fourteen). But the quest to understand the first stage is a search for an elusive people whose language and society lie veiled in the pre-literate past, even though they became world conquerors and founded today's dominant societies. That quest is also a great detective story, whose solution depends on a language discovered behind a secret wall in a Buddhist monastery, and on an Italian language inexplicably preserved on the linen wrappings of an Egyptian mummy.

When you first think about it, you might be excused for dismissing the Indo-European problem as obviously insoluble. Since the Indo-European mother tongue arose before the origin of writing, is it not almost by definition impossible to study? Even if we found the skeletons or pottery of the first Indo-Europeans, how would we recognize them? The skeletons and pottery of modern Hungarians, living in the centre of Europe, are as typically European as goulash is typically Hungarian. A future archaeologist excavating a Hungarian city would never guess that Hungarians speak a non-Indo-European language, if no examples of writing itself were recovered. Even if we could somehow locate the place and time of the first Indo-Europeans, how could we hope to deduce what advantage let their language triumph?

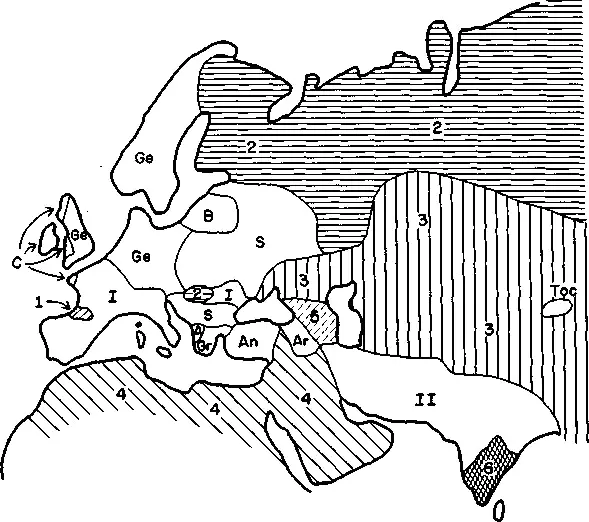

Remarkably, it turns out that linguists have been able to extract answers to these questions from the languages themselves. I shall explain why we are so confident that language distributions today reflect a steamroller in the past, then try to assess when and where the mother tongue was spoken, and how it managed to take over so much of the world. How can we infer that the modern Indo-European languages replaced other, now-vanished languages? I am not talking about the observed second-stage replacements of the past 500 years, which saw English and Spanish dislodge most native tongues of the Americas and Australia. Those modern expansions were obviously due to the advantages Europeans gained from guns, germs, iron, and political organization (Chapter Fourteen). Instead, I am talking about the inferred first-stage replacement that saw Indo-European dislodge older languages of Europe and western Asia, and that must have happened before writing reached those areas. The map on the following page shows the distribution of Indo-European language branches surviving in 1492, just before Spanish began to leap across the Atlantic with Columbus. Three branches are especially familiar to most Europeans and Americans: Germanic (including English and German), Italic (including French and Spanish), and Slavic (including Russian), each branch with twelve to sixteen surviving languages and 300 to 500 million speakers. The largest branch, however, is Indo-Iranian, with ninety languages and nearly 700 million speakers from Iran to India (including Romany, the language of gypsies). Relatively tiny surviving branches are Greek, Albanian, Armenian, Baltic (consisting of Lithuanian and Latvian), and Celtic (including Welsh and Gaelic), each with only two to ten million speakers. In addition, at least two Indo-European branches, Anatolian and Tocharian, vanished long ago but are known from extensive preserved writings, while others disappeared with less trace.

Indo-European

A Albanian

Ar Armenian

B Baltic

C Celtic

Ge Germanic

Gr GreeK

I Italic

II Indo-Iranian

S Slavic

An Anatolian"] extinct Toe Tocharianj

Non-Indo-European

1 WA Basque

2 I IFinno-Ugric

3 II I II Turkic and Mongolian

4 k\N Semitic

5 Exx^l Caucasian

6 ETO Dravidian

This map shows language distribution, circa 1492, just before the European discovery of the New World. There must have been other Indo-European language branches that had become extinct before then. However, lengthy written texts exist only in languages of the Anatolian branch (including Hittite) and the Tocharian branch, whose homelands became occupied by speakers of Turkic and Mongolian languages before 1492.

What proves that all these tongues are related to each other and distinct from other language stocks? One obvious clue is shared vocabulary, as illustrated by the table of vocabulary on page 226 and thousands of other examples. A second clue is similar word endings (so-called inflectional endings) used to form verb conjugations and noun declensions. These endings are illustrated by part of the conjugation of 'to be' below. It becomes easier to recognize such similarities when you realize that word roots and endings shared between related languages are generally not shared identically. Instead, a particular sound in one language is often replaced by another sound in the other language. Familiar examples are the frequent equivalence of English 'th' and German 'd' (English 'thing' equals German 'ding, 'thank' equals 'danke'), or of English V and Spanish 'es' (English 'school' equals 'escuela, 'stupid' equals 'estupido'). Those resemblances among the Indo-European languages are detailed, but much grosser features of sounds and word formation set Indo-European languages apart from other language families. For example, my atrocious French accent embarrasses me as soon as I open my mouth to ask, 'Ow est le metro' But my difficulties with French are nothing compared with my total inability to produce the click sounds of some southern African languages, or to produce the eight gradations of vowel pitch in the Lakes Plain languages of the New Guinea lowlands. Naturally, my Lakes Plain friends loved teaching me bird names that differed only in pitch from words for excrement, then watching me ask the next villager I met for more information about that 'bird'.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.