Jared Diamond - The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Jared Diamond - The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1991, ISBN: 1991, Издательство: RADIUS, Жанр: Биология, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee

- Автор:

- Издательство:RADIUS

- Жанр:

- Год:1991

- ISBN:0-09-174268-4

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

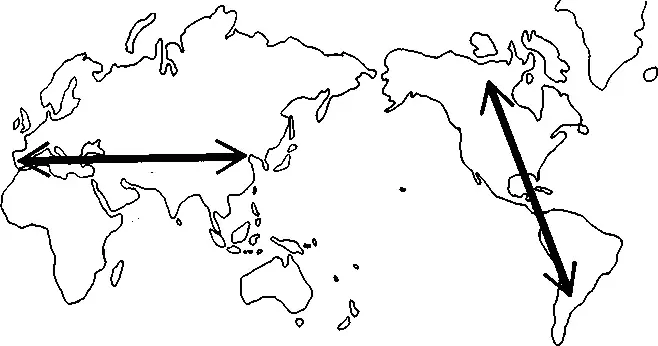

So far, I have discussed geography's biogeographic role, in providing the local wild animal and plant species suitable for domestication. But there is another major role of geography that deserves mention. Each civilization has depended not only on its own food plants domesticated locally, but also on other food plants that arrived after having been first domesticated elsewhere. The predominantly north/south axis of the New World made such diffusion of food plants difficult; the predominantly east/west axis of the Old World made it easy (see map overleaf). Today, we take plant diffusion so much for granted that we seldom stop to think where our foods originated. A typical American or European meal might consist of chicken (of Southeast Asian origin) with corn (from Mexico) or potatoes (from the southern Andes), seasoned with pepper (from India), accompanied by a piece of bread (from Near Eastern wheat) and butter (from Near Eastern cattle), and washed down by a cup of coffee (from Ethiopia). But this diffusion of valued plants and animals did not begin just in modern times: it has been happening for thousands of years.

Plants and animals spread quickly and easily within a climate zone to which they are already adapted. To spread out of this zone, they have to develop new varieties with different climate tolerances. A glance at the map of the Old World on this page shows how species could shift long distances without encountering a change of climate. Many of these shifts proved enormously important in launching farming or herding in new areas, or enriching it in old areas. Species moved between China, India, the Near East, and Europe without ever leaving temperate latitudes of the northern hemisphere. Ironically, the US patriotic song 'America the Beautiful' invokes America's own spacious skies, its amber waves of grain. In reality, the most spacious skies of the northern hemisphere were in the Old World, where amber waves of related grains came to stretch for 7,000 miles from the English Channel to the China Sea.

The Romans were already growing wheat and barley from the Near East, peaches and citrus fruits from China, cucumbers and sesame from India, and hemp and onions from central Asia, along with oats and poppies originating locally in Europe. Horses that spread from the Near East to West Africa revolutionized military tactics there, while sheep and cattle spread down the highlands of East Africa to launch herding in southern Africa among the Hottentots, who lacked locally domesticated animals of their own. African sorghum and cotton reached India by around 2000 BC, while bananas and yams from tropical Southeast Asia crossed the Indian Ocean to enrich agriculture in tropical Africa.

In the New World, however, the temperate zone of North America is isolated from the temperate zone of the Andes and southern South America by thousands of miles of tropics, in which temperate-zone species cannot survive. As a result, the llama, alpaca, and guinea-pig of the Andes never spread in prehistoric times to North America or even to Mexico, which consequently remained without any domestic mammals to carry packs or to produce wool or meat (except for corn-fed edible dogs). Potatoes also failed to spread from the Andes to Mexico or North America, while sunflowers never spread from North America to the Andes. Many crops that were apparently shared prehistorically between North and South America actually occurred as different varieties or even species in the two continents, suggesting that they were domesticated independently in both areas. This seems true, for instance, of cotton, beans, lima beans, chili peppers, and tobacco. Corn did spread from Mexico to both North and South America, but it evidently was not easy, perhaps because of the time it took to develop varieties suited to other latitudes. Not until around 900 AD—thousands of years after corn had emerged in Mexico—did corn become a staple food in the Mississippi Valley, thereby triggering the belated rise of the mysterious mound-building civilization of the American Midwest.

Thus, if the Old and New Worlds had each been rotated ninety degrees about their axes, the spread of crops and domestic animals would have been slower in the Old World, faster in the New World. The rates of rise of civilization would have been correspondingly different. Who knows whether that difference would have sufficed to let Montezuma or Atahuallpa invade Europe, despite their lack of horses?

I have argued, then, that continental differences in the rates of rise of civilization were not an accident caused by a few individual geniuses. They were not produced by the biological differences determining the outcome of competition among animal populations—for example, some populations being able to run faster or digest food more efficiently than others. They also were not the result of average differences among whole peoples in inventiveness; there is no evidence for such differences anyway. Instead, they were determined by biogeography's effect on cultural development. If Europe and Australia had exchanged their human populations twelve thousand years ago, it would have been the former native Australians, transplanted to Europe, who eventually mvaded America and Australia from Europe. Geography sets ground rules for the evolution, both biological and cultural, of all species, including our own. Geography's role in determining our modern political history is even more obvious than the role I have discussed in determining the rate at which we domesticate plants and animals. From this perspective, it is almost funny to read that half of all American schoolchildren do not know where Panama is, but not at all funny when politicians display comparable ignorance. Among the many notorious examples of disasters brought on by politicians ignorant of geography, two must suffice: the unnatural boundaries drawn on the map of Africa by nineteenth-century European colonial powers, thereby undermining the stability of some modern African states that inherited those borders; and the borders of Eastern Europe drawn at the Treaty of Versailles in 1919 by politicians who knew little of that region, thereby helping to fuel the Second World War. Geography used to be a required subject in US schools and colleges until a few decades ago, when it began to be dropped from many curricula. The mistaken belief arose then that geography consisted of little more than memorizing the names of capital cities. But twenty weeks of geography in the seventh grade is not enough to teach our future politicians about the effects that maps really have on us. The fax machines and satellite communications that span the globe cannot erase the differences among us bred by differences in location. In the long run, and on a broad scale, where we live has contributed heavily to making us who we are.

FIFTEEN

HORSES, HITTITES, AND HISTORY

More than 4,000 years before the recent expansion of Europeans over all other continents, there was an earlier expansion within Europe and western Asia that sired most of the languages spoken in that region today. Although those earlier conquerors were illiterate, much of their language and culture can be reconstructed from shared word roots preserved in modern Indo-European languages. Their conquest of much of Eurasia, like the subsequent overseas expansion of their descendants, appears to have been an accident of biogeography. 'Yksi, kaksi, kolme, nelja, viisi.

I watched the little girl counting out five marbles, one by one. Her was familiar, but her words were strange. Almost anywhere else Europe, I would have heard words like our English 'one, two, three' 'uno, due, tre' in Italy, 'ein, zwei, drei' in Germany, 'odin, dva, tri' in Russia. But I was vacationing in Finland, and Finnish is one of Europe's) non-Indo-European languages.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.