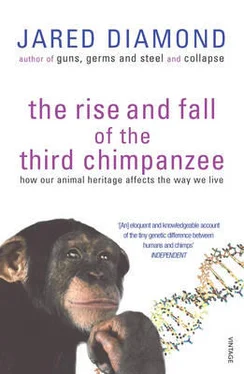

Jared Diamond - The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Jared Diamond - The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1991, ISBN: 1991, Издательство: RADIUS, Жанр: Биология, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee

- Автор:

- Издательство:RADIUS

- Жанр:

- Год:1991

- ISBN:0-09-174268-4

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Such considerations help explain the slow rate of human technological development in Australia. That continent's relative poverty in wild plants appropriate for domestication, as in appropriate wild animals, undoubtedly contributed to the failure of aboriginal Australians to develop agriculture. But it is not so obvious why agriculture in the Americas lagged behind that in the Old World. After all, many food plants now of worldwide importance were domesticated in the New World: corn, potatoes, tomatoes, and squash, to name just a few. The answer to this puzzle requires closer scrutiny of corn, the New World's most important crop. Corn is a cereal—that is, a grass with edible starchy seeds, like barley kernels or wheat grains. Cereals still provide most of the calories consumed by the human race. While all civilizations have depended on cereals, different native cereals have been domesticated by different civilizations: for instance, wheat, barley, oats, and rye in the Near East and Europe; rice, foxtail millet, and broomcorn millet in China and Southeast Asia; sorghum, pearl millet, and finger millet in sub-Saharan Africa; but only corn in the New World. Soon after Columbus discovered America, corn was brought back to Europe by early explorers and spread around the globe, and it now exceeds all other crops except wheat in world acreage planted. Why, then, did corn not enable American Indian civilizations to develop as fast as the Old World civilizations fed by wheat and other cereals?

It turns out that corn was a much bigger pain in the neck to domesticate and grow, and gave an inferior product. Those will be fighting words to all of you who, like me, love hot, buttered corn-on-the-cob. Throughout my childhood, I looked forward to late summer as the season to stop at roadside stands and pick out the best-looking fresh ears. Corn is the most important crop in the US today, worth twenty-two billion dollars to us and fifty billion dollars to the world. But before you charge me with slander, please hear me out on the differences between corn and other cereals. The Old World had over a dozen wild grasses that were easy to domesticate and grow. Their large seeds, favoured by the Near East's highly seasonal climate, made their value obvious to incipient farmers. They were easy to harvest en masse with a sickle, easy to grind, easy to prepare for cooking, and easy to sow. Another subtle advantage was first recognized by University of Wisconsin botanist Hugh Iltis: we did not have to figure out for ourselves that they could be stored, since wild rodents in the Near East already made caches of up to sixty pounds of those wild grass seeds.

The Old World grains were already productive in the wild, and one can still harvest up to 700 pounds of grain per acre from wild wheat growing naturally on hillsides in the Near East. In a few weeks a family could harvest enough to feed itself for a year. Even before wheat and barley were domesticated, there were sedentary villages in Palestine that had already invented sickles, mortars and pestles, and storage pits, and that were supporting themselves on wild grains. Domestication of wheat and barley was not a conscious act. It was not the case that several hunter-gatherers sat down one day, mourned the extinction of big game animals, discussed which particular wheat plants were best, planted the seeds of those plants, and thereby became farmers the next year. Instead, as I mentioned in Chapter Ten, the process we call domestication—the changes in wild plants under cultivation—was an unintended by-product of people preferring some wild plants over others, and hence accidentally spreading seeds of the preferred plants. In the case of wild cereals, people naturally preferred to harvest ones with big seeds, ones whose seeds were easy to remove from the seed-coverings, and ones with firm non-shattering stalks that held all the seeds together. It took only a few mutations, favoured by this unconscious human selection, to produce the large-seeded, non-shattering cereal varieties that we refer to as domesticated rather than wild. By around 8000 BC, wheat and barley remains from archaeological digs at ancient Near Eastern village sites are beginning to show these changes. The development of bread wheats, other domestic varieties, and intentional sowing soon followed. Gradually, fewer remains of wild foods are found at the sites. By 6000 BC, crop cultivation had been integrated with animal herding into a complete food production system in the Near East. For better or worse (in some major respects worse, as I argued in Chapter Ten), people were no longer hunter-gatherers but farmers and herders, en route to being civilized.

Now contrast these relatively straightforward Old World developments with what happened in the New World. The parts of the Americas where farming began lacked the Near East's highly seasonal climate, and so lacked large-seeded grasses that were already productive in the wild. North American and Mexican Indians did start to domesticate three small-seeded wild grasses called maygrass, little barley, and a wild millet, but these were displaced by the arrival of corn and then of European cereals. Instead, the ancestor of corn was a Mexican wild grass that did have the advantage of big seeds but in other respects hardly seemed like a promising food plant: annual teosinte.

Teosinte ears look so different from corn ears that scientists argued about teosinte's precise role in corn's ancestry till recently, and even now some scientists remain unconvinced. No other crop underwent such drastic changes on domestication as did teosinte. It has only six to twelve kernels per ear, and they are inedible, because they are enclosed in stone-hard cases. One can chew teosinte stalks like sugar cane, as Mexican farmers still do. But no one uses its seeds today, and there is no indication that anyone did prehistorically either.

Hugh Iltis identified the key step in teosinte's becoming useful: a permanent sex change! In teosinte the side branches end in a tassel composed of male flowers; in corn they end in a female structure, the ear. Although that sounds like a drastic difference, it is really a simple hormonally-controlled change that could have been started by a fungus, virus, or change in climate. Once some flowers on the tassel had changed sex to female, they would have produced edible naked grains likely to catch the attention of hungry hunter-gatherers. The tassel's central branch would then have been the beginning of a corn cob. Early Mexican archaeological sites have yielded remains of tiny ears, barely an inch-and-a-half long and much like the tiny ears of our 'Tom Thumb' corn variety.

With that abrupt sex change, teosinte (alias corn) was now finally on the road to domestication. However, in contrast to the case with Near Eastern cereals, thousands of years of development still lay ahead before high-yield corns capable of sustaining villages or cities resulted. The final product was still much more difficult for Indian farmers to manage than were the cereals of Old World farmers. Corn ears had to be harvested individually by hand, rather than en masse with a sickle; the cobs had to be shucked; the kernels did not fall off but had to be scraped or bitten off; and sowing the seeds involved planting them individually, rather than scattering them en masse. The result was still poorer nutritionally than Old World cereals: lower protein content, deficiencies of nutritionally important amino acids, deficiency of the vitamin niacin (tending to cause the disease pellagra), and need for alkali treatment of the grain to partially overcome these deficiencies.

In short, characteristics of the New World's staple food crop made its potential value much harder to discern in the wild plant, harder to develop by domestication, and harder to extract even after domestication. Much of the lag between New World and Old World civilization may have been due to those peculiarities of one plant.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.