The Radiolaria are one-celled animals whose protoplasm is contained in siliceous shells of extraordinary beauty. These minute shells, sinking to the bottom, accumulate there to form one of the characteristic oozes or sediments of the sea floor. The Foraminifera are another unicellular group. Most have calcareous shells, though some build their protective structures with sand grains or sponge spicules. The shells, eventually drifting to the floor of the ocean, cover vast areas with calcareous sediments that, through geologic change, may become compacted into limestone or chalk, and raised to form such features of the present landscape as the chalk cliffs of England. Most Foraminifera are so minute that one gram of sand might contain up to 50,000 shells. On the other hand, a fossil species, Nummulites, was sometimes 6 or 7 inches across and formed limestone beds in Northern Africa, Europe, and Asia. This limestone was used in the building of the Sphinx and the great pyramids. Fossil Foraminifera are much used by geologists in the oil industry in correlating rock strata.

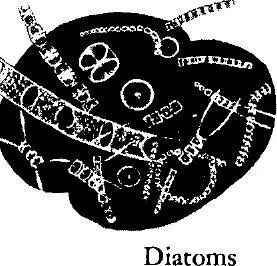

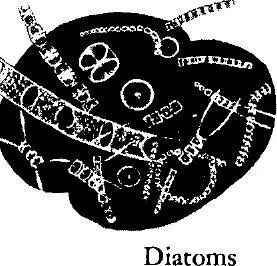

Diatoms (Greek, diatomos —cut in two) are minute plants usually classified among the yellow-green algae because they contain granules of yellow pigment. They exist as single cells or in chains of cells. The living tissue of a diatom is encased within a shell of silica, of which one half fits over the other, as a lid over a box. Fine etchings on the surface of the shell create beautiful patterns and are characteristic for the various species. Most diatoms live in the open sea, and because they exist in inconceivable abundance are the most important single food stuff in the ocean, being eaten not only by many small animals of the plankton, but by many larger creatures, as mussels and oysters. The hard shells sink to the bottom after the death of the tissues, and accumulate there to form diatom oozes that cover vast areas of ocean floor.

The blue-green algae, or Cyanophyceae, are among the simplest and oldest forms of life and are the most ancient plants that still exist. They are widely distributed and occur even in hot springs and other places where conditions are so difficult that no other plant life can exist. They often multiply in phenomenal numbers, giving the surface of ponds and other still waters a colored film known as water bloom. Most are encased in gelatinous sheaths that protect them from extreme heat or cold. They are well represented in the “black zone” above high-tide line on rocky shores.

Thallophyta: Higher Algae

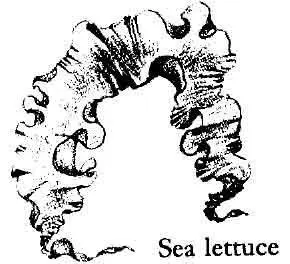

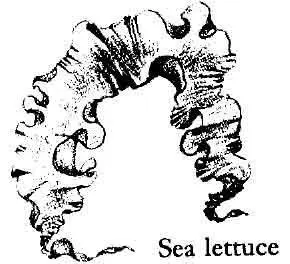

THE GREEN ALGAE, or Chlorophyceae, are able to endure strong light and thrive high in the intertidal zone. They include such familiar forms as the leafy sea lettuce and a stringy, tube-like alga of high rocks and tide pools called Enteromorpha (“intestine-shaped”). In the tropics some of the most common green algae are the brush-shaped Penicillus that forms minute groves over the coral reef flats, and the beautiful little cup alga, Acetabularia, like tiny, inverted mushrooms of purest green. Some of the green algae of the tropics are important in the economy of the sea as concentrators of calcium. Although the group is most typical of warm, tropical seas, the green algae are found on the shore wherever there is strong sunlight, and others of the group live in fresh water.

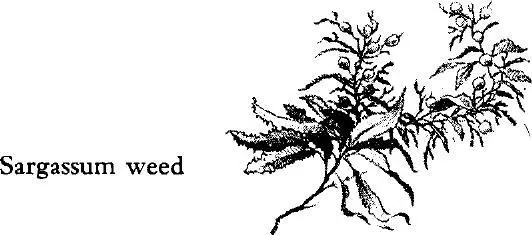

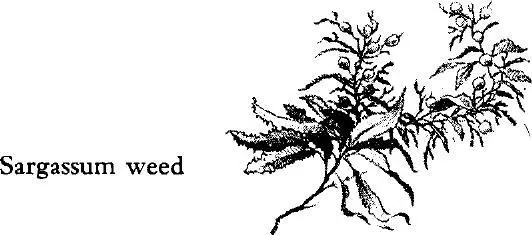

The brown algae, or Phaeophyceae, possess various pigments that conceal their chlorophyll, so their prevailing colors are brown, yellowish, or olive-green. They are largely absent from warmer latitudes except in deep water, being unable to endure heat and strong sun. An exception is the Sargassum weed of tropical shores, which drifts northward in the Gulf Stream. On northern coasts the brown rockweeds live between tide lines, and the kelps or oarweeds from the low-tide line down to depths of 40 to 50 feet. Although all of the algae select and concentrate in their tissues many different chemicals present in sea water, the brown seaweeds and especially the kelps are extraordinary in the quantity of iodine stored. Formerly they were utilized widely in the industrial production of iodine. The same seaweeds now are important in the production of the carbohydrate algin for use in fire-resistant textiles, jellies, ice cream, cosmetics, and various industrial processes. The presence of alginic acid gives these seaweeds their great resilience in heavy surf.

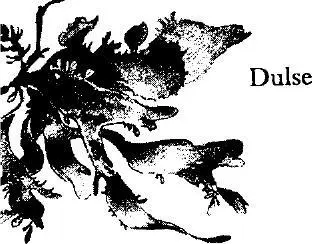

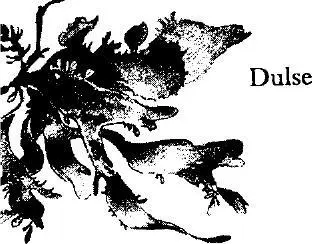

The red algae, or Rhodophyceae, most sensitive light of all the seaweeds, send only a few hardy species (including Irish moss and dulse) into the intertidal zone; most are delicate and graceful seaweeds living for the most part below low water. Some live deeper than any other seaweeds, going down into the dim regions 200 fathoms or more below the surface. Some (the corallines) form hard crusts on rocks or shells. Containing magnesium carbonate as well as calcium carbonate, these algae seem to have played an important geochemical role in earth history, perhaps having aided the formation of the magnesium-rich marble dolomite.

Porifera: Sponges

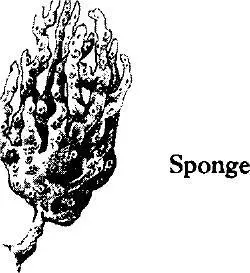

THE SPONGES (Porifera, or pore-bearers) are among the simplest of animals, being little more than an aggregation of cells. Yet they have gone a step beyond the Protozoa, for there are inner and outer layers of cells, with some hint of specialization of function—some for drawing in water, some for taking in food, some for reproduction. All these cells cohere and work together to carry out the single purpose of the sponge—to pass the waters of the sea through the sieves of its own being. A sponge is an elaborate system of canals contained in a matrix of fibrous or mineral substance, the whole pierced by numerous small entrance pores and larger exit holes. The inmost or central cavities are lined with flagellated cells that remind one of protozoan flagellates. The lashing of the whiplike flagella creates currents to draw in water. In passage through the sponge, the water gives up food, minerals, and oxygen, and carries away waste products.

To a certain extent, each of the smaller groups within the sponge phylum has a physical appearance and habit of life that is characteristic, yet the sponges are probably more plastic in relation to their environment than any other animals. In surf they take the form of a flattened crust, almost without regard to species; in deep, quiet water they may assume an upright tubular form, or branch in a way suggestive of shrubbery. Their shape, therefore, is little or no aid in identification, and the classification of sponges is based chiefly on the nature of their skeleton, which is a loose network of minute hard structures called spicules. In some the spicules are calcareous. In others they are siliceous, although sea water contains only a trace of silica and the sponge must have to filter prodigious quantities to obtain enough for its spicules. The function of extracting silica from sea water is confined to primitive forms of life, and among animals does not occur above the sponges. Commercial sponges fall into a third group, having a skeleton of horny fibers. They are confined to tropical waters.

Читать дальше