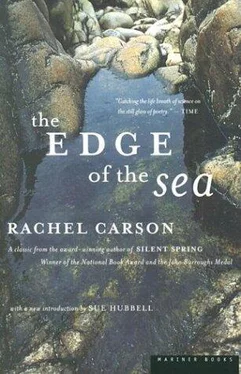

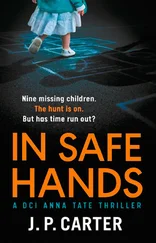

The Jonah crabs use the resilient cushion of moss as a hiding place to wait for the return of the tide or the coming of darkness. I remember a moss-carpeted ledge standing out from a rock wall, jutting out over sea depths where Laminaria rolled in the tide. The sea had only recently dropped below this ledge; its return was imminent and in fact was promised by every glassy swell that surged smoothly to its edge, then fell away. The moss was saturated, holding the water as faithfully as a sponge. Down within the deep pile of that carpet I caught a glimpse of a bright rosy color. At first I took it to be a growth of one of the encrusting corallines, but when I parted the fronds I was startled by abrupt movement as a large crab shifted its position and lapsed again into passive waiting. Only after search deep in the moss did I find several of the crabs, waiting out the brief interval of low tide and reasonably secure from detection by the gulls.

The seeming passivity of these northern crabs must be related to their need to escape the gulls—probably their most persistent enemies. By day one always has to search for the crabs. If not hidden deeply within the seaweeds, they may be wedged in the farthest recess afforded by an overhanging rock, secure there, in dim coolness, gently waving their antennae and waiting for the return of the sea. In darkness, however, the big crabs possess the shore. One night when the tide was ebbing I went down to the low-tide world to return a large starfish I had taken on the morning tide. The starfish was at home at the lowest level of these tides of the August moon, and to that level it must be returned. I took a flashlight and made my way down over the slippery rockweeds. It was an eerie world; ledges curtained with weed and boulders that by day were familiar landmarks seemed to loom larger than I remembered and to have assumed unfamiliar shapes, every projecting mass thrown into bold relief by the shadows. Everywhere I looked, directly in the beam of my flashlight or obliquely in the half-illuminated gloom, crabs were scuttling about. Boldly and possessively they inhabited the weed-shrouded rocks. All the grotesqueness of their form accentuated, they seemed to have transformed this once familiar place into a goblin world.

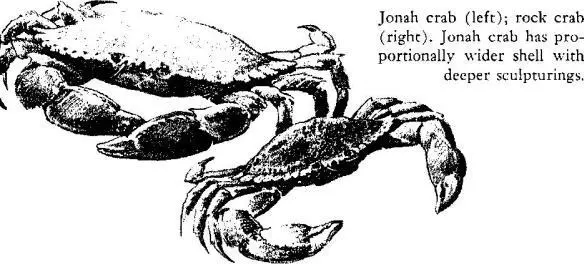

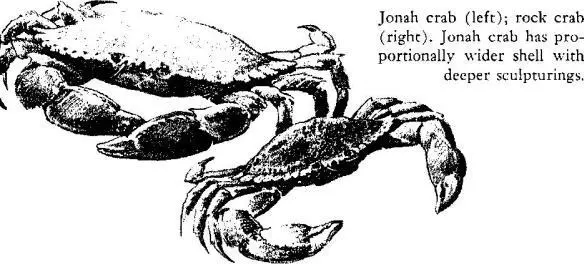

In some places, the moss is attached, not to the underlying rock, but to the next lower layer of life, a community of horse mussels. These large mollusks inhabit heavy, bulging shells, the smaller ends of which bristle with coarse yellow hairs that grow as excrescences from the epidermis. The horse mussels themselves are the basis of a whole community of animals that would find life on these wave-swept rocks impossible except for the presence and activities of the mollusks. The mussels have bound their shells to the underlying rock by an almost inextricable tangle of golden-hued byssus threads. These are the product of glands in the long slender foot, the threads being “spun” from a curious milky secretion that solidifies on contact with sea water. The threads possess a texture that is a remarkable combination of toughness, strength, softness, and elasticity; extending out in all directions they enable the mussels to hold their position not only against the thrust of incoming waves but also against the drag of the backwash, which in a heavy surf is tremendous.

Over the years that the mussels have been growing here, particles of muddy debris have settled under their shells and around the anchor lines of the byssus threads. This has created still another area for life, a sort of understory inhabited by a variety of animals including worms, crustaceans, echinoderms, and numerous mollusks, as well as the baby mussels of an oncoming generation—these as yet so small and transparent that the forms of their infant bodies show through newly formed shells.

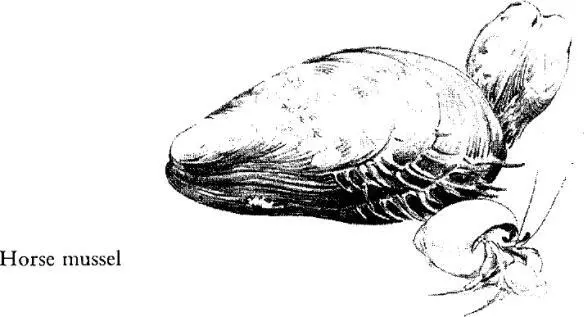

Certain animals almost invariably live among the horse mussels. Brittle stars insinuate their thin bodies among the threads and under the shells of the mussels, gliding with serpentine motions of the long slender arms. The scale worms always live here, too, and down in the lower layers of this strange community of animals starfish may live below the scale worms and brittle stars, and sea urchins below the starfish, and sea cucumbers below the urchins.

Of the echinoderms that live here, few are the largest individuals of their species. The blanket of horse mussels seems to be a shelter for young, growing animals, and indeed the full-grown starfish and urchins could hardly be accommodated there. In the waterless intervals of the low tide, the cucumbers draw themselves into little football-shaped ovals scarcely more than an inch long; returned to the water and fully relaxed, they extend their bodies to a length of five or six inches and unfurl a crown of tentacles. The cucumbers are detritus feeders, and explore the surrounding muddy debris with their soft tentacles, which periodically they pull back and draw across their mouths, as a child would lick his fingers.

In pockets deep in the moss under layers of mussels, a long, slender little fish of the blenny tribe, the rock eel, waits for the return of the tide, coiled in its water-filled refuge with several of its kind. Disturbed by an intruder, all thrash the water violently, squirming with eel-like undulations to escape.

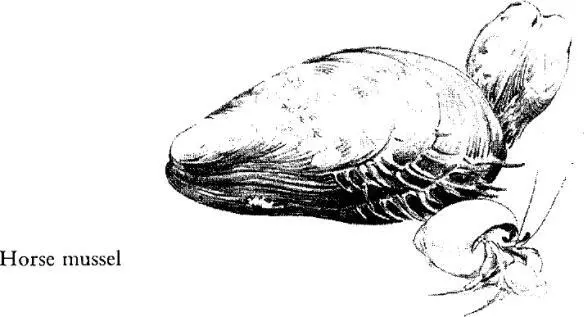

Where the big mussels grow more sparsely, in the seaward suburbs of this mussel city, the moss carpet, too, becomes a little thinner; but still the underlying rock seldom is exposed. The green crumb-of-bread sponge, which at higher levels seeks the shelter of rock overhangs and tide pools, here seems able to face the direct force of the sea and forms soft, thick mats of pale green, dotted with the cones and craters typical of this species. And here and there patches of another color show amid the thinning moss—dull rose or a gleaming, reddish brown of satin finish—an intimation of what lies at lower levels.

During much of the year the spring tides drop down into the band of Irish moss but go no lower, returning then toward the land. But in certain months, depending on the changing positions of sun and moon and earth, even the spring tides gain in amplitude, and their surge of water ebbs farther into the sea even as it rises higher against the land. Always, the autumn tides move strongly, and as the hunter’s moon waxes and grows round, there come days and nights when the flood tides leap at the smooth rim of granite and send up their lace-edged wavelets to touch the roots of the bayberry; on their ebbs, with sun and moon combining to draw them back to the sea, they fall away from ledges not revealed since the April moon shone upon their dark shapes. Then they expose the sea’s enameled floor—the rose of encrusting corallines, the green of sea urchins, the shining amber of the oarweeds.

At such a time of great tides I go down to that threshold of the sea world to which land creatures are admitted rarely in the cycle of the year. There I have known dark caves where tiny sea flowers bloom and masses of soft coral endure the transient withdrawal of the water. In these caves and in the wet gloom of deep crevices in the rocks I have found myself in the world of the sea anemones—creatures that spread a creamyhued crown of tentacles above the shining brown columns of their bodies, like handsome chrysanthemums blooming in little pools held in depressions or on bottoms just below the tide line.

Читать дальше