Against this background of glowing color the barnacles stand out with sharp distinctness, and in the clear water that pours through the forest like liquid glass, their cirri flicker in and out-extending, grasping, withdrawing, taking from the inpouring tides those minute atoms of life that our eyes cannot see. Around the bases of small wave-rounded boulders the mussels lie as though at anchor, held by gleaming lines spun by their own tissues. Their paired blue shells stand a little apart, the space between them revealing pale brown tissues with fluted edges.

Some parts of the forest are less open. In these the clumps of rockweeds rise from a short turf or undergrowth consisting chiefly of the flat fronds of Irish moss, with sometimes dark mats of another plant with the texture of Turkish toweling. And like a tropical jungle with its orchids, this sea forest has the counterpart of airplants in the epiphytic tufts of a red seaweed that grows on the fronds of the knotted wrack. Polysiphonia seems to have lost—or perhaps it never had—the ability to attach directly to the rocks and so its dark red balls of finely divided fronds cling to the wracks, and by them are lifted up into the water.

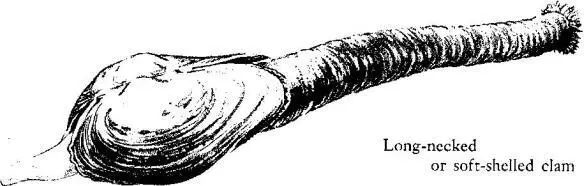

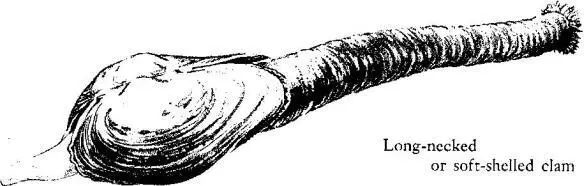

In the areas between the rocks and under loose boulders a substance that is neither sand nor mud has accumulated. It consists of minute and water-ground bits of the remains of sea creatures—the shells of mollusks, the spines of sea urchins, the opercula of snails. Clams live in pockets of this soft substance, digging down until they are buried to the tips of their siphons. Around the clams the mud is alive with ribbon worms, thin as threads, scarlet of color, each a small hunter searching out minute bristle worms and other prey. Here also are the nereids, given the Latin name for sea nymph because of their grace and iridescent beauty. The nereids are active predators that leave their burrows at night to search for small worms, crustaceans, and other prey. In the dark of the moon certain species gather at the surface in immense spawning swarms. Curious legends have become associated with them. In New England the so-called clam worm, Nereis virens, often takes shelter in empty clam shells. Fishermen, accustomed to finding it thus, believe it is the male clam.

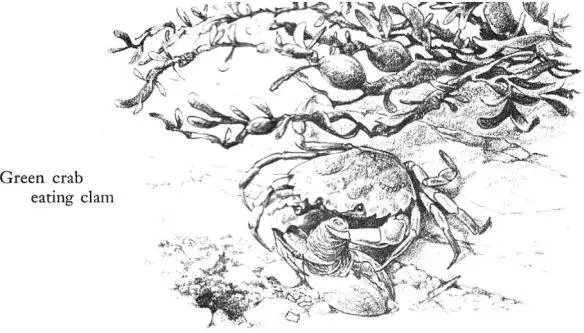

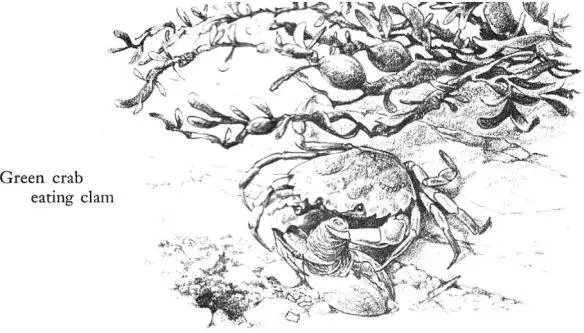

Crabs of thumbnail size live in the weed and come down to hunt in these areas. They are the young of the green crab; the adults live below the tide lines on this shore except when they come into the shelter of the weeds to molt. The young crabs search the mud pockets, digging out pits and probing for clams that are about their own size.

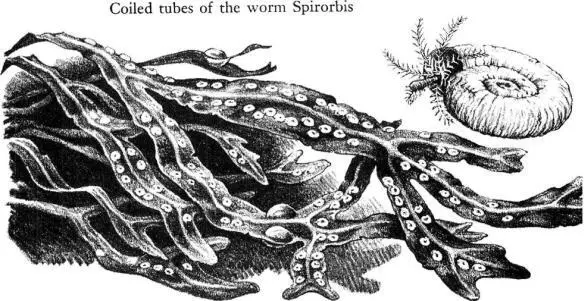

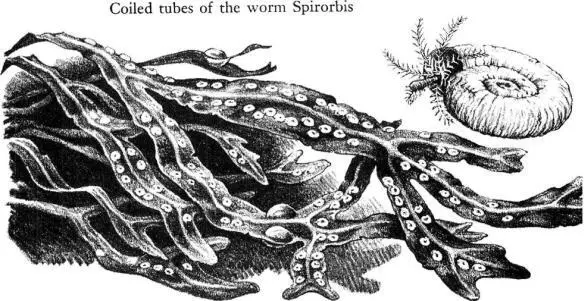

Clams, crabs, and worms are part of a community of animals whose lives are closely interrelated. The crabs and the worms are the active predators, the beasts of prey. The clams, the mussels, and the barnacles are the plankton feeders, able to live sedentary lives because their food is brought to them by each tide. By an immutable law of nature, the plankton feeders as a group are more numerous than those that prey on them. Besides the clams and other large species, the rockweeds shelter thousands of small beings, all of them busy with filtering devices of varying design, straining out the plankton of each tide. There is, for example, a small, plumed worm called Spirorbis. Seeing it for the first time, one would certainly say that it is no worm, but a snail, for it is a tube-builder, having learned some feat of chemistry that allows it to secrete about itself a calcareous shell or tube. The tube is not much larger than the head of a pin and is wound in a flat, closely coiled spiral of chalky whiteness, its form strongly suggesting some of the land snails. The worm lives permanently within the tube, which is cemented to weed or rock, thrusting out its head from time to time to filter food animals through the fine filaments of its crown of tentacles. These exquisitely delicate and filmy tentacles serve not only as snares to entangle food but as gills for breathing. Among them is a structure like a long-stemmed goblet; when the worm draws back into its tube the goblet or operculum closes the opening like a neatly fitted trap door.

The fact that the tube worms have managed to live in the intertidal zone for perhaps millions of years is evidence of a sensitive adjustment of their way of life, on the one hand to conditions within the surrounding world of the rockweeds, on the other to vast tidal rhythms linked with the movements of earth, moon, and sun.

In the inmost coils of the tube are little chains of beads wrapped in cellophane—or so they appear. There are about twenty beads in a chain. The beads are developing eggs. When the embryos have developed into larvae, the cellophane membranes rupture and the young are sent forth into the sea. By keeping the embryonic stages within the parental tube Spirorbis protects its young from enemies and assures that the infant worms will be in the intertidal zone when they are ready to settle. Their period of active swimming is short—at most an hour or so, and well contained within a single rising or falling of the tide. They are stout little creatures with bright red eye spots; perhaps the larval eyes help in locating a place for attachment but in any event they degenerate soon after the larva settles.

In the laboratory, under my microscope, I have watched the larvae swimming about busily, all their little bristles whirring, then sometimes descending to the glass floor of their dish to bump it with their heads. Why and how do the infant tube worms settle in the same sort of place their ancestors chose? Apparently they make many trials, reacting more favorably to smooth surfaces than to rough, and displaying a strong instinct of gregariousness that leads them to settle by preference where others of their kind are already established. These tendencies help to keep the tube worms within their comparatively restricted world. There is also a response, not to familiar surroundings, but to cosmic forces. Every fortnight, on the moon’s quarter, a batch of eggs is fertilized and taken into the brood chamber to begin its development. And at the same time the larvae that have been made ready during the previous fortnight are expelled into the sea. By this timing—this precise synchronizing with the phases of the moon—the release of the young always occurs on a neap tide, when neither the rise nor the fall of the water is of great extent, and even for so small a creature the chances of remaining within the rockweed zone are good.

Sea snails of the periwinkle tribe inhabit the upper branches of the weeds at high tide or take shelter under them when the tide is out. The orange and yellow and olive-green colors of their smoothly rounded, flat-topped shells suggest the fruiting bodies of the rockweeds, and perhaps the resemblance is protective. The smooth periwinkle, unlike the rough, is still an animal of the sea; the salty dampness it requires is provided by the wet and dripping fronds of the seaweeds when the tide is out. It lives by scraping off the cortical cells of the algae, seldom if ever descending to the rocks to feed on the surface film as related species do. Even in its spawning habits the smooth periwinkle is a creature of the rockweeds. There is no shedding of eggs into the sea, no period of juvenile drifting in the currents. All the stages of its life are lived in the rockweeds—it knows no other home.

Читать дальше