The limpet’s relations with other inhabitants of the shore are simple. It lives entirely on the minute algae that coat the rocks with a slippery film, or on the cortical cells of larger algae. For either purpose, the radula is effective. The limpet scrapes the rocks so assiduously that fine particles of stone are found in its stomach; as the teeth of the radula wear away under hard use they are replaced by others, pushed up from behind. To the algal spores swarming in the water, ready to settle down and become sporelings and then adult plants, the limpets stand in the relation of enemy, since they keep the rocks scraped fairly clean where they are numerous. By this very act, however, they render a service to barnacles, making easier the attachment of their larvae. Indeed, the paths radiating out from a limpet’s home are sometimes marked by a sprinkling of the starlike shells of young barnacles.

In its reproductive habits this deceptively simple little snail seems again to have defied exact observation. It seems certain, however, that the female limpet does not make protective capsules for her eggs in the fashion typical of many snails, but commits them directly to the sea. This is a primitive habit, followed by many of the simpler sea creatures. Whether the eggs are fertilized within the mother’s body or while floating at sea is uncertain. The young larvae drift or swim for a time in the surface waters; the survivors then settle down on rocky surfaces and metamorphose from the larval to the adult form. Probably all young limpets are males, later transforming to females—a circumstance not at all uncommon among mollusks.

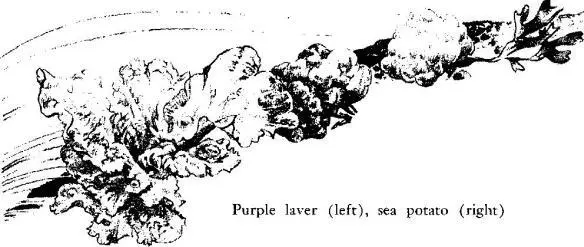

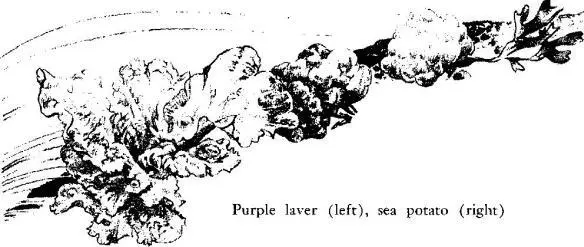

Like the animal life of this coast, the seaweeds tell a silent story of heavy surf. Back from the headlands and in bays and coves the rockweeds may grow seven feet tall; here on this open coast a seven-inch plant is a large one. In their sparse and stunted growth, the seaweed invaders of the upper rocks reveal the stringent conditions of life where waves beat heavily. In the middle and lower zones some hardy weeds have been able to establish themselves in greater abundance and profusion. These differ so greatly from the algae of quieter shores that they are almost a symbol of the wave-swept coast. Here and there the rocks sloping to the sea glisten with sheets composed of many individual plants of a curious seaweed, the purple laver. Its generic name, Porphyra, means “a purple dye.” It belongs to the red algae, and although it has color variations, on the Maine coast it is most often a purplish brown. It resembles nothing so much as little pieces of brown transparent plastic cut out of someone’s raincoat. In the thinness of its fronds it is like the sea lettuce, but there is a double layer of tissue, suggesting a child’s rubber balloon that has collapsed so that the opposite walls are in contact. At the stem of the “balloon” Porphyra is attached strongly to the rocks by a cord of interwoven strands—hence its specific name, “umbilicalis.” Occasionally it is attached to barnacles and very rarely it grows on other algae instead of directly on hard surfaces. When exposed at ebb tide under a hot sun, the laver may dry to brittle, papery layers, but the return of the sea restores the elastic nature of the plant, which, despite its seeming delicacy, allows it to yield unharmed to the push and pull of waves.

Down at the lower tidal levels is another curious weed—Leathesia, the sea potato. It grows in roughly globular form, its surface seamed and drawn into lobes, forming fleshy, amber-colored tubers that are any size up to an inch or two in diameter. Usually it grows around the fronds of moss or another seaweed, seldom if ever attaching directly to the rocks.

The lower rocks and the walls of low tide pools are thickly matted with algae. Here the red weeds largely supplant the browns that grow higher up. Along with Irish moss, dulse lines the walls of the pools, its thin, dull red fronds deeply indented so that they bear a crude resemblance to the shape of a hand. Minute leaflets sometimes haphazardly attached along the margins create a strangely tattered appearance. With the water withdrawn, the dulse mats down against the rocks, paper-thin layers piled one upon another. Many small starfish, urchins, and mollusks live within the dulse, as well as in the deeper growth of Irish moss.

Dulse is one of the algae that have a long history of usefulness to man, as food for himself and his domestic animals. According to an old book on seaweeds, it used to be said in Scotland that “he who eats of the Dulse of Guerdie and drinks of the wells of Kildingie will escape all maladies except black death.” In Great Britain, cattle are fond of it and sheep wander down into the tidal zone at low water in search of it. In Scotland, Ireland, and Iceland people eat dulse in various ways, or dry it and chew it like tobacco; even in the United States, where such foods are usually ignored, it is possible to buy dulse fresh or dried in some coastal cities.

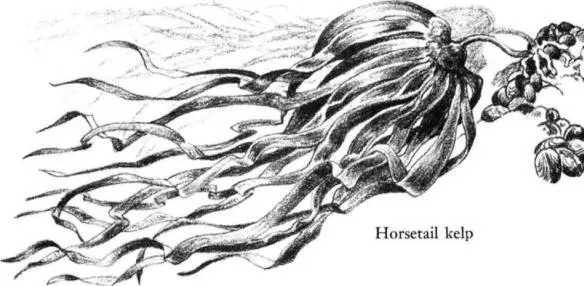

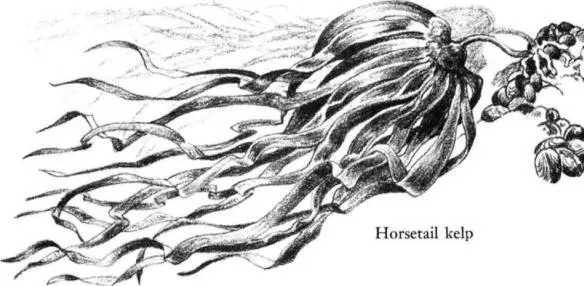

In the very lowest pools the Laminarias begin to appear, called variously the oarweeds, devil’s aprons, sea tangles, and kelps. The Laminarias belong to the brown algae, which flourish in the dimness of deep waters and polar seas. The horsetail kelp lives below the tidal zone with others of the group, but in deep pools also comes over the threshold, just above the line of the lowest tides. Its broad, flat, leathery frond is frayed into long ribbons, its surface is smooth and satiny, and its color richly, glowingly brown.

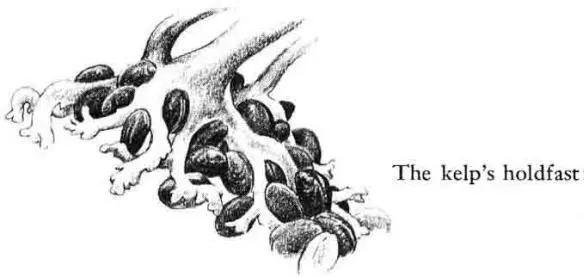

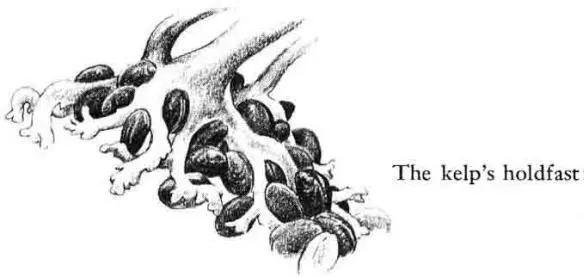

The water in these deep basins is icy cold, filled with dusky, swaying plants. To look into such a pool is to behold a dark forest, its foliage like the leaves of palm trees, the heavy stalks of the kelps also curiously like the trunks of palms. If one slides his fingers down along such a stalk and grips just above the holdfast, he can pull up the plant and find a whole microcosm held within its grasp.

One of these laminarían holdfasts is something like the roots of a forest tree, branching out, dividing, subdividing, in its very complexity a measure of the great seas that roar over this plant. Here, finding secure attachment, are plankton-strainers like mussels and sea squirts. Small starfish and urchins crowd in under the arching columns of plant tissue. Predacious worms that have foraged hungrily during the night return with the daylight and coil themselves into tangled knots in deep recesses and dark, wet caverns. Mats of sponge spread over the holdfasts, silently, endlessly at their work of straining the waters of the pool. One day a larval bryozoan settles here, builds its tiny shell, then builds another and another, until a film of frosty lace flows around one of the rootlets of the seaweed. And above all this busy community, and probably unaffected by it, the brown ribbons of the kelp roll out into the water, the plant living its own life, growing, replacing torn tissues as best it may, and in season sending clouds of reproductive cells streaming into the water. As for the fauna of the holdfasts, the survival of the kelp is their survival. While it stands firm their little world holds intact; if it is torn away in a surge of stormy seas, all will be scattered and many will perish with it.

Читать дальше