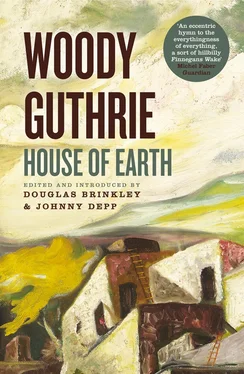

HOUSE OF EARTH

A NOVEL

WOODY GUTHRIE

Edited and Introduced by

Douglas Brinkley and Johnny Depp

TO

Nora Guthrie

AND

Tiffany Colannino

AND

Guy Logsdon

I ain’t seen my family in twenty years

That ain’t easy to understand

They may be dead by now

I lost track of them after they lost their land

—BOB DYLAN, “Long and Wasted Years”

And seeing the multitudes, he went up into a mountain: and when he was set, his disciples came unto him:

And he opened his mouth, and taught them, saying,

Blessed are the poor in spirit: for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

Blessed are they that mourn: for they shall be comforted.

Blessed are the meek: for they shall inherit the earth.

—MATTHEW 5:1–5 ( King James Version )

CONTENTS

CONTENTS

Dedication

Epigraph

Introduction

I DRY ROSIN

II TERMITES

III AUCTION BLOCK

IV HAMMER RING

Acknowledgments

Selected Bibliography

Selected Discography

Biographical Time Line

About the Author

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

INTRODUCTION

Life’s pretty tough. . . . You’re lucky ifyou live through it .

—WOODY GUTHRIE

On Sunday, April 14, 1935—Palm Sunday—the itinerant sign painter and folksinger Woody Guthrie thought the apocalypse was knockin’ on the door of Pampa, Texas. An immense dust cloud—one that had emanated from the Dakotas—swept grimly across the Panhandle, like the Black Hills on wheels, blotting out sky and sun. As the dust storm approached the town, the bright afternoon was eclipsed by an ominous darkness. Fear engulfed the community. Had its doom arrived? No one in Pampa was safe from this beast. Huddled around a lone lightbulb in a shabby, makeshift wooden house with family and friends, Guthrie, a Christian believer, prayed for survival. The demented winds fingered their way through the loose-fitting windows, cracked walls, and wooden doors of the house. The people in Guthrie’s tight quarters held wet rags over their mouths, desperate to keep the swirling dust from asphyxiating them. Breathing even shallowly and irregularly was an exercise in forbearance. Guthrie, eyes shut tight, face firm, kept coughing and spitting mud.

What Guthrie experienced in Pampa, a vortex in the Dust Bowl, he said, was like “the Red Sea closing in on the Israel children.” According to Guthrie, for three hours that April afternoon a terrified Pampan couldn’t see a “dime in his pocket, the shirt on your back, or the meal on your table, not a dadgum thing.” When the dust storm finally passed, locals shoveled dirt from their front porches and swept basketfuls of debris from inside their houses. Guthrie, incessantly curious, tried to reconcile the joy of being alive with the widespread despair. He surveyed the damage in Pampa the way a veteran reporter would have done. The engines of the usually reliable G.M. motorcars and Fordson tractors had been ruined by thick grime. Huge dunes had accumulated in corrals and alongside wooden ranch homes. Most of the livestock had perished in the storm, the sand clogging their throats and noses. Even vultures hadn’t survived the maelstrom. Images of human anguish were everywhere. Some old people, hit the hardest, had suffered permanent damage to their eyes and lungs. “Dust pneumonia,” as physicians called the many cases of debilitating respiratory illness, became an epidemic in the Texas Panhandle. Guthrie would later write a song about it.

To express his sympathy for the survivors of that Palm Sunday, Guthrie wrote a powerful lament, which set the tone and tenor of his career as a Dust Bowl balladeer:

On the fourteenth day of April ,

Of nineteen thirty-five ,

There struck the worst of dust storms

That ever filled the sky .

You could see that dust storm coming

It looked so awful black ,

And through our little city ,

It left a dreadful track .

In the spring of 1935, Pampa was not the only town that had been punished by the agony and losses of the four-year drought. Sudden dust cyclones—black, gray, brown, and red—had also ravaged the high, dry plains of Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Texas, Colorado, and New Mexico. Still, nothing had prepared the region’s farmers, ranchers, day laborers, and boomers for the Palm Sunday when a huge black blob and dozens of other, smaller dust clouds quickly developed into one of the worst ecological disasters in history. Vegetation and wildlife were destroyed far and wide. By summer, the hot winds had sucked up millions of bushels of topsoil, and the continuing drought devastated agriculture in the lowlands. Poor tenant farmers became even poorer because their fields were barren. Throughout the Great Depression, the Great Plains underwent intolerable torment. The prolonged drought of the early 1930s had destroyed crops, eroded land, and caused many deaths. Thousands of tons of dark topsoil, mixed with red clay, had been blown down to Texas from the Dakotas and Nebraska, carried by winds of fifty to seventy miles per hour. A sense of hopelessness prevailed. But the indefatigable Guthrie, a documentarian at heart, decided that writing folk songs would be a heroic way to lift the sagging morale of the people.

Confronted with dreariness and absurdity, with poor folks in distress, many of them financially ruined by the Dust Bowl, Guthrie turned philosophical. There had to be a better way of living than in rickety wooden lean-tos that warped in the summer humidity, were vulnerable to termite infestation, lacked insulation in subzero winter weather, and blew away in a sandstorm or a snow blizzard. Guthrie realized that his neighbors needed three things to survive the Depression: food, water, and shelter. He decided to concern himself with the third in his only fully realized novel: the poignant House of Earth .

A central premise of House of Earth —first conceived in the late 1930s but not fully composed until 1947—is that “wood rots.” At one point in Guthrie’s narrative, there is a tirade against forestry products that rot down … sway … keel over. Someone curses at a wooden home: “Die! Fall! Rot!” Scarred by the dust storm of April 14, Guthrie, a socialist, damned Big Agriculture and capitalism for the degradation of the land. If there is an overall ethos in House of Earth , it’s that those with power—especially Big Banks, Big Lumber, Big Agriculture—should be chastised as repugnant robber barons and rejected by wage earners. Woody was a union man. But his harangues against the powers that be are also tinged with self-doubt. Can one person really fight against wind, dust, and snow? Isn’t venting one’s spleen futile in the end?

Читать дальше

CONTENTS

CONTENTS